По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

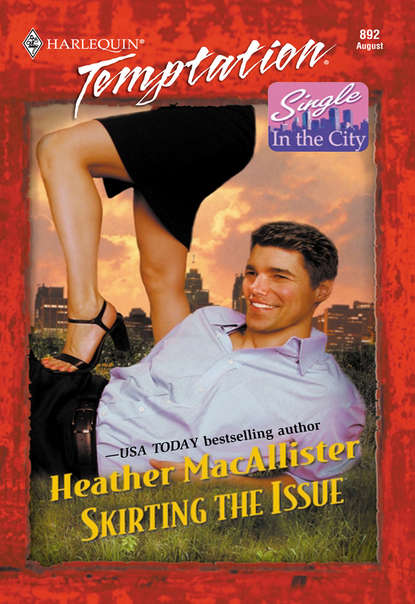

Skirting The Issue

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Today, Sam had been at her desk two hours early and was taking a long lunch, determined to find some place to live, or at least a cheaper hotel.

She pushed open the door to the post office, thankful for the air-conditioning. She did miss San Francisco’s temperate weather.

Because it was noontime, there was a line at the post office, but Sam figured there was always going to be a line in New York and she might as well get used to it. Sam got at the end of the line, which looped back on itself three times like an amusement park ride. Since all the clerk windows were open, the wait shouldn’t be more than twenty minutes or so. And if it was longer, well, what could she do about it?

She fanned herself with her soft bulky package. In it was the skirt. She’d never had so much attention as she’d had since catching the thing at Kate’s wedding. School friends she hadn’t heard from in years had contacted her for progress reports. And magazines, too, for pity’s sake! There had been articles about the thing. And not one, but two reporters had tracked her down here in New York.

And then there were all the women who’d e-mailed her to check on her progress. Good grief. She hadn’t even worn the thing, not counting that hideous evening right after she’d caught it when Kevin had insisted that she try it on and she’d hoped it wouldn’t fit.

It had. It had fit as though it had been made for her. Sam was a tall woman—five-ten in flats which she wore because she felt like it and not to de-emphasize her height—and the skirt flirted with the top of her knees.

Kevin had wanted to flirt with the top of her knees, too, and insisted she wear the new addition to her wardrobe to dinner. He loved the skirt. Sam couldn’t see why. It was black and maybe shorter than she generally wore, but not outrageously so. Nothing special. The material that had seemed so rich and warmly luxurious earlier was now sleazy and limp. It wasn’t doing anything for her. Unfortunately, neither was Kevin. She didn’t want to wear it to dinner, which Kevin had taken as an invitation to skip dinner for other pursuits when that hadn’t been Sam’s intention at all.

Kevin had become obnoxious and Kevin was never obnoxious. He’d made a cryptic remark about willing to buy the whole cow instead of settling for milk—another animal metaphor—and that she should appreciate it. She didn’t. They’d argued and Sam had been forced to tell him right then that she’d decided to come to New York after all.

He’d blamed the skirt, which was so incredibly stupid she couldn’t believe it, but, understanding that his pride had been hurt, Sam had allowed it.

She never intended to wear the skirt again, let alone throw it at her nonexistent wedding. Why would she want to mess up her life just when it was getting interesting? And the thing that really chapped her was that Kevin had just assumed that Sam would give up her chance at a promotion to stay in San Francisco with him. It never occurred to him to move to New York with her, not that she wanted him to, but still. He never got it; he never understood that he expected her to make the big sacrifice without considering making one of his own.

The sound of crumpling paper as she squeezed the package brought Sam back to the present.

Inhaling, she cleared her mind of all things Kevin. New York air could do that to a person. In spite of her mother’s tempting suggestion that she do all womankind a favor and burn it, Sam intended to mail the skirt back to Kate. That’s all there was to it.

She smoothed out the label. Let Kate invite some desperately single candidates to an elegant little luncheon where she could use all her bridal china and throw the thing at them.

Exhaling, Sam massaged the muscles in her neck, relaxing because for once, no one she knew was watching her or comparing her to the other job candidates.

Yes, competing for a position was a particularly effective form of torture in hotel management circles, no doubt thought of by a high-paid consultant who’d never actually experienced the unrelenting pressure of being scrutinized for days on end. Carrington’s executive board was always hiring consultants. If she got the job—and maybe if she didn’t—she was going to tell them what they could do with their consultants. Diplomatically, of course, because even though somebody was going to crack soon, it wasn’t going to be Sam.

There were to have been four candidates for the position of east coast convention sales manager, but one had declined, citing a reluctance to relocate to New York City—the wimp—so it was now Sam and two men. Her mother had been calling for nightly updates and to give Sam feminist pep talks. Sam’s mother had been a foot soldier in the war between the sexes and considered Sam one of her best weapons.

Sam was perfectly willing to be a weapon. As the youngest of four girls, she hadn’t often had her mother’s undivided attention—if ever—and enjoyed talking strategy and letting off steam.

This past week, managers from all the hotels in the eastern quadrant of the United States had been meeting at the flagship Carrington near Times Square. Sam and her two colleagues had been running meetings, preparing theater outings, and getting to know the managers and their hotels. Of course Sam had met some of them before when she’d contracted with groups to hold conventions at their hotels, but as the east coast manager, she’d be expected to become familiar with all the little quirks about their hotels. It wouldn’t hurt to get chummy with them, either, her mother reminded her, but Sam wasn’t a chummy sort of person. Some people just didn’t know the difference between chummy and suggestive. Josh Crandall, for instance.

Or they did and ignored it.

Like Josh Crandall.

The line moved forward and Sam hunched her shoulders, wishing she’d splurged on a massage with the hotel masseuse. Today was judgment day. There was only one meeting—one big, giant, important, possibly life-altering meeting—and Sam and the other candidates weren’t attending. Their convention sales records were being scrutinized. Sam had a spectacular sales record—except for two blotches. Sizable blotches, if she were being truthful. And both were courtesy of Josh Crandall of Meckler Hotels.

Sam closed her eyes. The very thought of him made her stomach queasy, the kind of queasy she got after eating too much chocolate in a short amount of time, which she usually did after going head-to-head with Josh.

Recently he’d been turning up every time she had a presentation. And now she was imagining him. She opened her eyes and checked out the people in line with her, involuntarily looking for his dark, carefully tousled hair and deceptively casual, but well-cut plaid sports coat. Oh, and the smile. That you-want-me-and-we-both-know-it smile.

She hated that smile. And he knew it.

Sam had a sudden craving for M&M’s.

Even now, the Carrington brass were probably dissecting her failed proposals. They’d been perfect, she knew, but still each convention had chosen Josh and the Meckler chain over Carrington. And because her proposals had been perfect, that meant the decisions had been based on intangibles, such as the charm of the representatives. In other words, they’d liked Josh better than Sam, which meant the failure had been hers, personally. Josh had no problem being chummy. Or suggestive, either.

It wasn’t that she’d never bested him before—or after—those incidences, it was that since then, she’d been too quick to make concessions to Carrington’s profit margin in order to ensure she never lost to him again.

The last time…Sam sucked her breath between her teeth—she really needed some chocolate—the last time, she’d cut profit to the bone. But instead of countering, Josh had laughed—his laughs dripped with evil amusement—then admitted he hadn’t wanted the convention anyway because the group in question was known for damaging hotel rooms.

And they had. Sam winced.

So, maybe Josh had won three times.

Stop thinking about him. It would only make her crazy. Sam deliberately wiped Josh and his smile from her mind and concentrated on the people around her. There were a couple of conversations going on—office workers mailing company letters and two good-looking, well-dressed men, well-dressed if she discounted the leather cowboy vest one wore and she was inclined to until she realized it was fake leather. And…and that the green color was not a trick of the light. Still, even with green faux leather with, she swallowed, silver fringe, they compared favorably to Josh and his stupid plaid jackets—if she’d been thinking about Josh, which she wasn’t.

The two men were one loop behind Sam and approached her as the line wound toward the counter windows. One man held a stack of printed postcards and the other man stuck preaddressed labels on them.

“Tavish, every year you go through this,” said the man with titanium glasses. “Stop waiting until the last minute.”

“But I always find a sublet,” replied Tavish, the taller of the two.

Sam liked tall men and it had nothing to do with her own height. Josh was tall—not that it mattered.

“But you don’t even investigate the tenants first!”

Tavish stuck on another label. “I go by instinct.”

“Someday your instincts are going to leave you with a trashed apartment.”

“Then it’ll be time to redecorate.” He looked off into the distance. “I’m growing weary of sage.”

If he’d asked, Sam could have told him what colors were predicted to be popular in the next couple of years. Carrington was building a new hotel in Trenton and she’d seen the reports from the decorating team. Colors were going to be clean and complex, whatever that meant. She made a mental note to find out. It might be important for her to know.

“And you always send these cards. Haven’t you heard of e-mail?”

“Who can keep up with everyone’s e-mail address? All those letters and dots and symbols…” Tavish grimaced.

“Who can keep up with your summer addresses?”

“That’s why I send the cards.”

The men had moved behind her. Sam was now passing by the supply counter and people kept reaching in front of her for forms, labels and envelopes. She was relieved when she moved by it, looped around, and several minutes later faced the two men again. Tavish was still peeling off labels and sticking them on his postcards. He apparently had a large acquaintanceship.

“Didn’t you just go on safari a couple of years ago?”

Tavish laughed, a warm rich chuckle that was oh-so-different from Josh’s predatory cackle—not that she was thinking about Josh Crandall while standing in line at a New York City post office. That would be foolish.

“There are safaris and there are safaris,” Tavish replied.

“An elephant is an elephant is an elephant.”

“But the aptly named Mona Virtue will be a member of the group.”