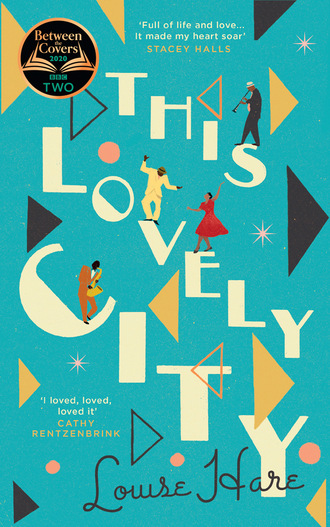

This Lovely City

He strained his arm and caught an inch of fabric between two fingers. Pulling gently, the bundle moved closer and he grabbed a tighter hold. The wool was heavy with water. White and yellow embroidered flowers peeked out from beneath the pond filth. Daisies. When he lifted it the bundle was heavier than he’d anticipated, but it wasn’t the weight that sent him crashing to the ground – only sheer luck landing him onto the bank rather than into the water. His heart pounded his ribs so hard that he glanced down at his chest, expecting to see it burst out through his coat, scattering buttons onto the ground.

The blanket lay there on the grass, the bundle coming apart. A baby’s arm had escaped, along with a shock of dark curly hair and a glimpse of a cheek. It could have been a doll, but one touch had been enough to convince him that it wasn’t. The hand was frozen stiff but the skin gave as his fingers had brushed against it.

Someone had left a baby in the pond to die. A baby whose skin was as dark as Lawrie’s.

2

Typing had a rhythm to it that Evie enjoyed. When she was in a good mood, more often than not these days, she sang along quietly to the tapping of the keys as she transcribed Mr Sullivan’s letters. He called her his little songbird and had been known to pat her on the head like a child, but he was a nice older gentleman and she knew she was lucky to have him. When his last secretary had left to get married, Evie had only been in the typing pool for a few months. Mr Sullivan’s single stipulation for her replacement was that she should be the fastest and most accurate typist. Mrs Jones, the pool supervisor, had sent Evie upstairs with a sly smile on her lips, and Evie had braced herself for his polite excuse but Mr Sullivan’s jaw had only dropped half an inch when he saw her, quickly masked by a smile, and it was Evie who had skipped back downstairs to whisk away Mrs Jones’s smirk along with her coat and bag.

She loved her job at Vernon & Sons. A light and airy office on the third floor, a desk by the window so that she could indulge in the odd daydream, and her best friend sitting right opposite. Delia was attached, professionally speaking, to the young Mr Vernon, the boss’s son, and would fix a tight smile to her face each time she had to untangle herself from his wandering hands and their clammy palms, her head turned away from his halitosis. As Ma often said, thank goodness Evie had not been born pretty and blonde. Not that Delia was a bad typist, only the young Mr Vernon had his own set of requirements when it came to secretaries.

‘I’ll be off now, Evie.’ Mr Sullivan emerged from his office, hat on head and overcoat slung over an arm. ‘I’m taking a slightly longer lunch today but you won’t tell anyone, will you?’ He winked and grinned, in the manner of a kindly uncle to his favourite niece.

Evie smiled conspiratorially. ‘I’ll not say a word. Off anywhere special?’

‘Just to see the kiddies.’ His eldest daughter had two of her own now and lived just off Lavender Hill, only up the road. ‘I’ll be back by three if anyone needs me.’

She waved him off. It was one o’clock and the offices were all emptying out; she could hear doors opening and closing throughout the three floors that the company occupied, echoing up and down the staircase. The girls would be heading to the small staffroom, or outside if they were brave enough, to eat their sandwiches. The men would be going out to a café or home for a hot meal, to see their wives, or mistress in the case of the young Mr Vernon – he’d packed his wife off to Surrey during the war and never thought to bring her back.

‘You almost done?’ Delia whizzed a sheet of paper from her typewriter with a flourish. ‘I’m starving.’

‘Two ticks.’ Evie locked her drawer. Things had a habit of going missing when she didn’t.

‘Off out are you?’

Evie looked up, stifling a groan. The suspected thief herself was standing in the doorway, her lip curling upwards in a sneer as she stared at Evie.

‘Hello, Mildred,’ Delia said, raising her voice. ‘Can we help you?’

Mildred sidled into the room. ‘We’re having a whip round for Hilda. She’s getting married a week on Saturday.’

‘Hilda?’ Delia pulled a thoughtful face, pretending she didn’t know who she was. Hilda and Mildred were thick as thieves, each as spiteful as the other. ‘Is she one of the typing pool girls? They all look the same to me.’

Evie saw Mildred’s face flush.

‘Are you going to put anything in or not?’

‘I think I can spare a bit of change.’ Delia reached for her purse and dropped a few coins into Mildred’s palm.

Mildred scowled and closed her hand around the loose pennies. ‘Don’t worry, Evie, I don’t expect you to chip in. I know you’re hard up.’

Evie’s jaw dropped as Mildred smirked, disappearing before Evie could think of a smart retort.

‘I’d love to give her a good smack,’ Delia said.

Delia had been Evie’s best friend since the first day of school. All the little girls and boys had been dressed up in new uniforms, drowning in oversized clothes that their mothers prayed they would not outgrow before year end. Agnes Coleridge knew well by then what the other mothers would whisper about her at the school gates, and she wouldn’t give them more ammunition than they already had. A talented seamstress, she had sewed Evie’s hem so that she had a properly fitting skirt that could be let out as she grew. Evie had cried that morning as her mother cursed and plaited her hair, pulling tighter until she’d quashed its rebellion. Ma had wiped her daughter’s tears with a damp flannel and kissed her forehead roughly.

At the school gates Evie had been unsure. Most of the children seemed to know one another but the Coleridges had only just moved to Brixton from Camberwell the week before. Ma had given her a little shove towards the teacher and told her she’d be back at the end of the school day. Miss Linton was young and smiley, her glasses making her hazel eyes look like giant marbles. She was too young to know what to do when Mildred had thwarted her seating plan by refusing to sit next to Evie. Delia was the one who shoved her hand straight in the air when Miss Linton asked for a volunteer to change places.

Like a bad smell Mildred had always been there in the background, impossible to get rid of. Nothing wound Mildred up more than knowing that Evie and Delia occupied privileged desks upstairs while she languished down in the typing pool with her poor WPM and tardy timekeeping. Evie had caught her before, sneaking around her desk when she thought that Evie had left for the day. She fingered the key to her desk drawer lightly and dropped it into her pocket.

‘Usual?’ Delia asked.

Evie nodded as they pulled on their coats and went downstairs, emerging onto St John’s Road, just up from Clapham Junction station. The street was busy as usual, buses piling down in both directions, but they were only heading to the café next door.

‘Egg and chips twice and tea for two, please.’ Delia waved the menu away as they sat at their usual table, delivering their order to the waitress. ‘Honestly, I don’t know why she bothers asking. Are you seeing Lawrie tonight?’

Evie shook her head. ‘The band got a regular Thursday night gig in Soho. It’ll be just another evening in with Ma. She’s taken on too much piecework again and I said I’d help out.’ Not that she’d have been given a choice but it felt better to imagine that her mother was like anyone else’s.

‘What about tomorrow after work? Fancy coming shopping? I need to get some new shoes. These ones are worn through.’ Delia stuck her leg out from under the table so that Evie could see the stretched leather, her big toe almost through at the front as she wiggled it around.

‘All right but it’ll have to be quick. I want to see Lawrie before he goes into town – Friday nights they play at the Lyceum.’ She barely saw Lawrie during the week these days; a musician in great demand, their relationship was becoming a series of stolen moments between their day jobs and the band’s growing popularity.

Delia smiled wryly. ‘I see how it is. Lawrie comes first. You’ll be getting married before long and I’ll never see you no more. You’ll be spending your days baking pies for Lawrie’s tea and popping out beautiful brown children for him. And you’ll remember that once you had a friend who you used to have fun with but now she’s a dried-up old spinster and you don’t have time for her.’

‘Stop it!’ They were both giggling now. ‘Besides you’re a long way off becoming a spinster. And if I do get married then you’ll get to be my bridesmaid.’

‘I’ve been a bridesmaid. Twice. It’s not as exciting as you seem to imagine.’ Delia’s nose wrinkled.

They both fell silent while the waitress plonked down a heavy tray laden with teapot, cups and saucers, milk, sugar.

‘Tell you what we should do.’ Delia lifted the lid to check on the tea, determining that longer was required. ‘Let’s go to the Lyceum tomorrow night and see Lawrie play.’

Evie bit back her immediate response, to say that her mother wouldn’t let her. She was eighteen after all. She could leave home any time she wanted, marry Lawrie if she felt like it without having to ask permission. And she’d rather face up to Ma than lie.

‘Yes, let’s do it,’ she said, with more resolution than she felt.

Their food arrived and Delia wondered aloud if a dress the colour of her vivid egg yolk might not suit Evie. Evie laughed and shook her head, looking up to see their waitress standing at the door just behind Delia, deep in conversation with a local bobby. The policeman had popped in to grab what looked like a sandwich, parcelled up in paper, but something in the urgency of his manner made her stop and listen in closer, tuning out Delia.

‘… don’t know what the world’s coming to,’ the waitress was saying, holding out the bag.

‘Not the sort of thing you expect round here,’ the policeman agreed. ‘Something’s changed, and not for the better.’ He glanced at Evie as he spoke, his face flushing crimson as she held his gaze. He grabbed his paper bag and left with a nod to the waitress.

‘… and of course even bloody Mildred’s waltzing round on the arm of a chap these days,’ continued Delia, oblivious to Evie’s wandering attention. ‘Jack flipping Bent of all people.’

‘You wouldn’t want to be stepping out with him though, would you?’ Evie turned back to her friend. ‘Nothing much going on between them dirty ears of his.’ It was Evie’s turn to wrinkle her nose.

‘But there’s been no one decent since Lennie,’ Delia complained.

‘Really? You’re saying that man’s name in the same sentence as the word “decent”?’ Evie laughed. ‘You could do so much better, Dee. You’ll see, I bet you, tomorrow night you’ll be batting them away. And if not you can come backstage, meet the band.’ She said it as a joke but regretted it immediately.

‘Oh no, no penniless musicians for me, thank you,’ Delia said, before quickly looking down at her yolk-smeared plate. ‘I mean, Lawrie’s one of a kind, ain’t he? He’s got a proper job, not just scraping by playing a few tunes.’

‘Everything all right?’ The waitress came to clear their plates and broke the awkward silence that had descended upon the two friends.

‘Lovely thank you,’ Evie told her, remembering what she’d overheard. ‘Excuse me, sorry, I didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but that policeman who was just in – did I hear him say that there’s been a murder?’

The waitress leaned down to speak in a hushed voice. ‘They found a baby drowned in one of the ponds on Clapham Common. Terrible, ain’t it?’

The girls nodded, wide-eyed, and the waitress carried off their empty plates.

‘Who’d do such an awful thing?’ Evie exclaimed, as Delia pulled a packet of Player’s cigarettes and a box of matches from her bag. ‘I suppose it’ll be in the papers tomorrow.’ She took the cigarette that was offered.

‘People shouldn’t be allowed to have children if they aren’t willing to do what’s best for them.’ Delia struck a match forcefully and held it out.

‘Maybe some people don’t have a choice.’ Evie leaned into the flame, inhaling deeply.

‘I don’t believe that. Most of us know to do what’s best. You know that.’ Delia blew a smoke ring, thinking it over. ‘That place is still open, isn’t it? Where your mother went.’

‘I suppose.’ Evie didn’t like to think about what might have happened if her mother had abandoned her there, at the home for unmarried mothers just off Clapham Common, not far from where this poor mite had been found. ‘Either way, they deserve to suffer, whoever’d do that to a child,’ she said finally.

As they packed up their things and prepared to head back to the office, Delia slid the topic of conversation back to the more pleasant territory of fashion. They decided to go along to Arding and Hobbs before they had to go back to work. Maybe she should think about buying something new to wear to the Lyceum. Lawrie might be working, but it would be their first proper night out together, and Evie wanted to look the part.

3

The room they’d left him in was inhospitable, but he supposed that was the point. Barely bigger than a large cupboard, it was windowless and even colder than outside. Lawrie watched his warm breath swirl like smoke beneath the harsh flickering of the bare fluorescent tube above him. Its relentless blinking made his head ache. The rectangular table before him was empty but for his own hands, fingers splayed across its dull scratched surface and his fingernails full of the same pond mud that coated his trousers and his coat. He wanted to change, to wash away the dirt on his hands that was making him itch. He’d asked for a glass of water but the policeman who’d left him in the room had not replied. Distant male voices could be heard along the corridor and he felt a coward for not going out there and demanding they give him something to drink.

The detective would be in soon. That’s what they’d told him. And it wasn’t like he was under arrest. He’d given a brief account by the side of the pond, his head turned away from that sad bundle on the grass. The constable had asked him to walk back to the station with him and give a full statement. Lawrie hadn’t been able to think of a good enough excuse for not complying.

Eyes open, eyes closed, it made no difference. He could still see that tiny hand and the curl of black hair fixed in his vision, hear the hiccupping sobs of the dog walker. He’d turned away when the foolish constable began to unwrap the blanket that Lawrie had closed up out of respect, staggering back with a yelp as he discovered why the woman was so upset. Served him right for doubting them, but for a moment Lawrie had hoped – had prayed – that he was mistaken. The woman had been allowed to leave once she’d given her brief version of events. She reckoned she hadn’t touched the body, though how she could have seen the baby without doing so, Lawrie didn’t know. He could still feel the weight of the bundle in the muscles that ran up his right arm, could still feel the swift release of that tension as he’d let it fall to the ground.

The door opened. ‘Lawrence Matthews?’ Lawrie nodded as the man entered. ‘Detective Sergeant Rathbone.’

The detective was smartly dressed, his jacket pressed and his dark navy tie neatly knotted. In his thirties, Lawrie guessed, with a narrow moustache and pockmarked cheeks that cried out for a beard. He sat down opposite and placed a manila folder between them. He didn’t look at Lawrie.

Rathbone pulled out a notebook, a packet of cigarettes and his matches, laying them neatly by the folder. He took a cigarette from the pack, not offering one to Lawrie. Striking a match, he sucked the flame into the open tobacco before shaking it out and dropping the spent match to the floor. There was no ashtray, and Lawrie found the careless action irritating, his lips turning upwards a little as he realised how ridiculous it was to bother about such a small thing.

‘What you smiling at?’ Rathbone looked up suddenly.

‘Nothing, sir.’ Lawrie leaned back and swallowed, his throat dry. ‘I just had a silly thought. That you could do with an ashtray.’

Rathbone cupped his hand behind his ear. ‘I can’t make out what you’re saying, son. You’ll have to speak more clearly if you’re going to keep on in that accent.’

‘Yes, sir.’ He slowed the pace of his words, but not too much in case Rathbone thought he was trying to be funny.

The detective pulled a pencil from his jacket pocket. ‘From the beginning then. Since this morning. I want to know exactly what you did, who you saw, everything. I’ll tell you if I want you to stop.’

‘Since this morning?’ Lawrie’s forehead creased as he thought back. ‘I left the house just before five o’clock.’ He paused and Rathbone waved him on. ‘Went to work same as always.’

‘You’re a postman?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Could this man not see the uniform he was wearing? ‘Sir, is there any chance of a glass of water?’

Rathbone arched an eyebrow. ‘Don’t change the subject. I said I’d let you know if I wanted you to stop talking.’

Lawrie blinked. ‘Yes, sir. Well, after I clocked off, around midday, I decided to go for a ride to Clapham Common.’

‘Why there? Why not Brockwell Park, somewhere closer to home?’

‘The sun was out and I thought… well, the Common is where I first stayed when I arrived in this country, see. I like it there.’ His palms were sweating now, thinking about that damned parcel. Guilt must be written all over his face.

Rathbone put down his pencil and looked him directly in the eye for the first time. ‘This all seems rather coincidental, don’t you think? Way I see it, you had no good reason for being by Eagle Pond.’

‘Wrong place, wrong time is all. I mean, do I need a purpose to use the Common? Does anybody?’ Oh God, he was babbling now. ‘Sir, it’s just a park after all. I was just passing by, I go there all the time. At least twice a week.’

Rathbone stared; Lawrie looked away first.

‘It is rather convenient though, you must admit.’ Rathbone tapped ash from his cigarette onto the floor. ‘A baby dies, through some manner or other, to be determined. Perhaps it’s a loved child, perhaps it was an accident or the family couldn’t afford a burial, perhaps at least the person responsible for her death regrets it. That’s what it looks like to me. He doesn’t want her body to go unfound. So he waits until dark before placing her body by the edge of the pond, knowing that people walk their dogs there. Then he starts to worry – what if she isn’t found? He goes back to check and lo! There comes our Mrs—’ Rathbone checked his notes. ‘Barnett. Perfect timing. She panics and, seeing a man on a bicycle, she runs towards him seeking sanctuary. He steps in and rescues the body as planned so it gets a proper burial. Make sense?’

‘The last bit, about her running towards me, yes.’ Lawrie sat up and leaned forward. ‘She was the one who found the…’ His tongue wouldn’t form the word. He’d barely touched the child but he could still feel the slip of its – her – skin against his, the catch of her tiny fingernails as he’d snatched his hand away. ‘You’ve got the woman’s statement right there in front of you. She was there first. She was the one made me go and look.’

‘Because there was no one else there.’ Rathbone fired out the words. ‘No one around but a nigger on a bicycle. You think she’d have gone to you for help if there’d been a single other person around?’

‘I don’t… I mean… what’s that got to do with me?’ Lawrie felt small all of a sudden, unprepared. He took a breath and tried to order his words. ‘I just went there for some fresh air, not looking for trouble.’

‘So when she says that you cycled past the pond once, then again not ten minutes later, you don’t think that seems like odd behaviour?’

‘No! And I did a good thing, helping that woman. I coulda just cycled off, you know? She was acting all hysterical, like a madwoman. And that dog of hers… But I could see there was something very wrong. I stopped to help.’

‘So what? You’re some kind of good Samaritan then?’ Rathbone sneered.

‘My mother brought me up to have good Christian values.’ Lawrie fought the rising wave of humiliation that made his skin prickle. His mother would be horrified if she could see him now.

More notes were made with that sharp pencil. Lawrie tried to swallow but his mouth was too dry; he coughed uncomfortably as his breath caught in his throat.

‘You saw the baby though.’ Rathbone watched him keenly. ‘Definitely one of your lot, wouldn’t you say? Maybe it wasn’t you after all, maybe you were just helping a pal?’

Lawrie looked down as his hands, clenching them together in his lap to stop the shaking. They’d told him he wasn’t under arrest but he couldn’t imagine that the interrogation would be any more severe if he had been. He understood now why they had brought no water to him. He was supposed to be uncomfortable. They thought he was a murderer. At best Rathbone had him down as an accomplice. The air around him felt as thick as the bright yellow custard that Mrs Ryan served up for pudding on Sundays, too dense to breathe properly. Should he just confess? Tell Rathbone about the parcel he’d been delivering? But what if the woman at Englewood Road denied it?

‘You’ve nothing to add?’ Rathbone paused before letting out a weary sigh. ‘If I find out later that you’ve lied, things will go very badly for you, you know?’

‘I’ve told you everything I know.’ Lawrie blinked as more smoke was blown in his direction. Rathbone’s cigarette, together with the nicotine haze hangover from the jazz club the night before, was making his eyes smart. At this rate he may as well take up the habit himself. ‘I don’t know what else I can tell you. Speak to my boss. He’ll tell you that I spent the morning doing my job, not hanging around that pond like a ghoul. Talk to my landlady. I never been married, never had a child.’ Just in time he stopped himself from mentioning Evie. He didn’t want this man going round to the Coleridges’, questioning Evie about him while her disapproving mother looked on. ‘I’m not the only coloured person in London, you know.’

‘You’re speaking too quickly again.’ Rathbone raised his voice. ‘You seem agitated. Why is that?’

‘I’m not agitated, I’m just tired is all.’ He hadn’t slept for over twenty hours and fatigue was dulling his mind. ‘I’m hungry. And thirsty. I been here for hours and not even been given any water to drink.’

‘This ain’t The Ritz, son. We don’t do silver service here.’ Rathbone barked a laugh. ‘Look, you was the only darkie anywhere near the scene of the crime. No good reason for being there.’ Rathbone leaned forward until Lawrie could smell the stale tobacco on his breath, overflowing like a used ashtray. ‘Between you and me, I don’t give two shits about some dead nigger baby. Too many of you around here already, but the law is the law. A suspicious death has to be investigated and someone has to hang for it.’ He let the threat catch in the air before going on. ‘Tell me what I need to know and I can make sure it don’t come to that. I’ll get you a bed. A hot meal. A fresh brew. I tell you something, our cells are far more comfortable than some of them places your lot live in.’

Lawrie felt his chest tighten as his eyes pricked with tears; he would rather die than shed them in front of this man. He thought of his brother; Bennie would never let a man like Rathbone get the better of him.

Rathbone opened his mouth to speak once more but was interrupted by a knock at the door. A younger man entered, also in plain clothes but less senior by the way he held his body as he nodded apologetically at Rathbone, who sighed and stood, following his colleague outside. Lawrie checked his watch again. It would be dark out now. Would the evening papers have printed the story already? What if the police had given his name? Donovan would kill him if they mentioned that he worked for the Post Office. A journalist had already been snooping around outside the police station when Lawrie propped his bicycle up against the wall of the building, hoping that the location was enough insurance against it being nicked. The reporter had been too focused on firing questions at the constable to have really looked at Lawrie, but that had been hours ago now. Plenty of time for someone to let a name slip.