По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

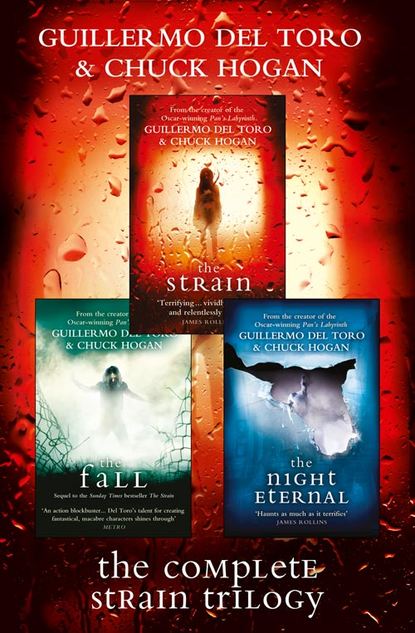

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He hit it two more times, first slow and easy, then hard and fast, the spring action on the plunger sticking as though from disuse.

The van creaked again, and Gus did not allow himself to look back.

The garage door was made of faceless steel, no grip handles. Nothing to pull. He kicked it once and the thing barely rattled.

Another bang from inside the van, almost answering his own, followed by a severe creak, and Gus rushed back to the plunger. He hit it again, rapid-fire, and then a pulley whirred and the motor clicked and the chain started running.

The door began lifting off the ground.

Gus was outside before it was halfway up, scuttling up onto the sidewalk like a crab and then quickly catching his breath. He turned and waited, watching the door open, hold there, and then go back down again. He made certain it closed tightly and that nothing emerged.

Then he looked around, shaking off his nerves, checking his hat—and walked to the corner, guilty fast, wanting to put another block between him and the van. He crossed to Vesey Street and found himself standing before the Jersey barriers and construction fences surrounding the city block that had been the World Trade Center. It was all dug out now, the great basin a gaping hole in the crooked streets of Lower Manhattan, with cranes and construction trucks building up the site again.

Gus shook off his chill. He unfolded his phone at his ear.

“Felix, where are you, amigo?”

“On Ninth, heading downtown. Whassup?”

“Nothing. Just get here pronto. I’ve done something I need to forget about.”

Isolation Ward, Jamaica Hospital Medical Center

EPH ARRIVED AT the Jamaica Hospital Medical Center, fuming. “What do you mean they’re gone?”

“Dr. Goodweather,” said the administrator, “there was nothing we could do to compel them to remain here.”

“I told you to post a guard to keep that Bolivar character’s slimy lawyer out.”

“We did post a guard. An actual police officer. He looked at the legal order and told us there was nothing he could do. And—it wasn’t the rock star’s lawyer. It was Mrs. Luss the lawyer. Her firm. They went right over my head, right to the hospital board.”

“Then why wasn’t I told this?”

“We tried to get in touch with you. We called your contact.”

Eph whipped around. Jim Kent was standing with Nora. He looked stricken. He pulled out his phone and thumbed back through his calls. “I don’t see …” He looked up apologetically. “Maybe it was those sunspots from the eclipse, or something. I never got the calls.”

“I got your voice mail,” said the administrator.

He checked again. “Wait … there were some calls I might have missed.” He looked up at Eph. “With so much going on, Eph—I’m afraid I dropped the ball.”

This news hollowed out Eph’s rage. It was not at all like Jim to make any mistake whatsoever, especially at such a critical time. Eph stared at his trusted associate, his anger fizzling out into deep disappointment. “My four best shots at solving this thing just walked out that door.”

“Not four,” said the administrator, behind him. “Only three.”

Eph turned back to her. “What do you mean?”

Inside the isolation ward, Captain Doyle Redfern sat on his bed, inside the plastic curtains. He looked haggard; his pale arms were resting on a pillow in his lap. The nurse said that he had declined all food, claiming stiffness in his throat and persistent nausea, and had rejected even tiny sips of water. The IV in his arm was keeping him hydrated.

Eph and Nora stood with him, masked and gloved, eschewing full barrier protection.

“My union wants me out of here,” said Redfern. “The airline industry policy is, ‘Always blame pilot error.’ Never the airline’s fault, overscheduling, maintenance cutbacks. They’re going to go after Captain Moldes on this one, no matter what. And me, maybe. But—something doesn’t feel right. Inside. I don’t feel like myself.”

Eph said, “Your cooperation is critical. I can’t thank you enough for staying, except to say that we’ll do everything in our power to get you healthy again.”

Redfern nodded, and Eph could tell that his neck was stiff. He probed the underside of his jaw, feeling for his lymph nodes, which were quite swollen. The pilot was definitely fighting off something. Something related to the airplane deaths—or merely something he had picked up over the course of his travels?

Redfern said, “Such a young aircraft, and an all-around beautiful machine. I just can’t see it shutting down so completely. It’s got to be sabotage.”

“We’ve tested the oxygen mix and the water tanks, and both came back clean. Nothing to indicate why people died or why the plane went dark.” Eph massaged the pilot’s armpits, finding more jelly-bean-size lymph nodes there. “You still remember nothing about the landing?”

“Nothing. It’s driving me crazy.”

“Can you think of any reason the cockpit door would be unlocked?”

“None. Completely against FAA regulations.”

Nora said, “Did you happen to spend any time up in the crew rest area?”

“The bunk?” Redfern said. “I did, yeah. Caught a few z’s over the Atlantic.”

“Do you remember if you put the seat backs down?”

“They were already down. You need the leg room if you’re stretching out up there. Why?”

Eph said, “You didn’t see anything out of the ordinary?”

“Up there? Not a thing. What’s to see?”

Eph stood back. “Do you know anything about a large cabinet loaded into the cargo area?”

Captain Redfern shook his head, trying to puzzle it out. “No idea. But it sounds like you’re on to something.”

“Not really. Still as baffled as you are.” Eph crossed his arms. Nora had switched on her Luma light and was going over Redfern’s arms with it. “Which is why your agreeing to stay is so critical right now. I want to run a full battery of tests on you.”

Captain Redfern watched the indigo light shine over his flesh. “If you think you can figure out what happened, I’ll be your guinea pig.”

Eph nodded their appreciation.

“When did you get this scar?” asked Nora.

“What scar?”

She was looking at his neck, the front of his throat. He tipped his head back so that she could touch the fine line that showed up deep blue under her Luma. “Looks almost like a surgical incision.”

Redfern felt for it himself. “There’s nothing.”

Indeed, when she switched off the lamp, the line was all but invisible. She turned it back on and Eph examined the line. Maybe a half inch across, a few millimeters thick. The tissue growth over the wound appeared quite recent.