По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

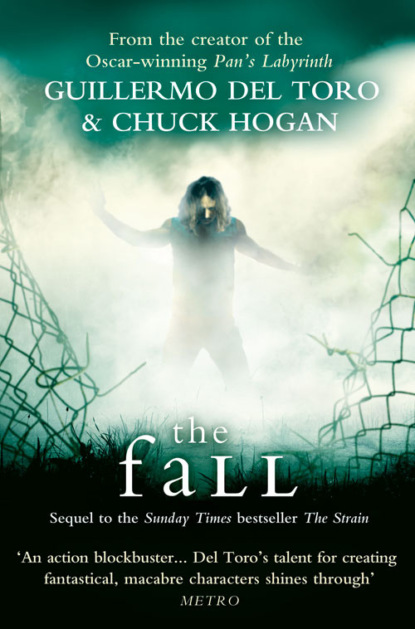

The Fall

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“What’s it like? I’m one of the last ones here.”

“Last ones?” said Eph. He noticed, for the first time, the shabby outline of a few tents and cardboard housings. After a moment, a few more spectral figures emerged. The “Mole People,” denizens of the urban abyss, the fallen, the disgraced, the disenfranchised, the “broken windows” of the Giuliani era. This was where they eventually found their way to, the city below, where it remained warm 24/7, even in the dead of winter. With luck and experience, one could camp at a site for as many as six months at a time, even more. Away from the busier stations, some resided for years without ever seeing a maintenance crew.

Cray-Z looked at Eph with his head turned to favor his one good eye. The other one was covered in granulated cataracts. “That’s right. Most all the colony is gone—just like the rats. Yeah, man. Vanished, leaving them fine valuables behind.”

He gestured at discarded piles of junk: ragged sleeping bags, muddy shoes, some coats. Fet felt a pang, knowing that these articles represented the sum total of the worldly possessions of the recently departed.

Cray-Z smiled a vacant smile. “Unusual, man. Downright spooky.”

Fet remembered something he had read in National Geographic, or maybe watched one night on the History channel: the story of a colony of settlers in the pre-America era—in Roanoke, maybe—who vanished one day. Over a hundred people, gone, leaving behind all of their belongings but no clues to their sudden and mysterious departure, nothing except two cryptic carvings: the word CROATOAN written into a post on their fort, and the letters CRO whittled into the bark of a nearby tree.

Fet looked again at the mosaic SF tiled onto the high wall.

“I know you,” said Eph, keeping a polite distance from the reeking Cray-Z. “I’ve seen you around—I mean, up there.” He pointed toward the surface. “You carry one of those signs, GOD IS WATCHING YOU, or something like that.”

Cray-Z smiled a mostly toothless smile and went and pulled out his hand-drawn placard, proud of his celebrity status. GOD IS WATCHING YOU!!! in bright red, with three exclamation points for emphasis.

Cray-Z was indeed a semi-delusional zealot. Down here, he was an outcast among outcasts. He had lived underground as long as anyone—maybe longer. He claimed that he could get anywhere in the city without surfacing—and yet he apparently lacked the ability to urinate without splashing the toes of his shoes.

Cray-Z moved alongside the tracks, motioning for Eph and Fet to follow. He ducked inside a tarp-and-pallet shack, where old, nibbled extension cords wound away up into the roof, wired into some hidden source of electricity on the great city grid.

It had begun to drizzle lightly within the tunnel, weeping ceiling pipes wetting the dirt, their water splattering onto Cray-Z’s tarp and running down into a waiting Gatorade bottle.

Cray-Z emerged carrying an old promotional cutout of former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, flashing his trademark “How’m I Doing?” smile. “Here,” he said, handing the life-sized photo to Eph. “Hold this.”

Cray-Z then walked them to the far tunnel, pointing down its tracks.

“Right into there,” he said. “That’s where they all went.”

“Who? The people?” said Eph, setting Mayor Koch down next to him. “They went into the tunnel?”

Cray-Z laughed. “No. Not just the tunnel, shithead. Down there. Where the pipes at the curve go under the East River, across to Governor’s Island, then over to mainland Brooklyn at Red Hook. That’s where they took them.”

“Took them?” said Eph, a chill trickling down his spine. “Who—who took them?”

Just then, a track signal lit up nearby. Eph jumped back. “This track still active?”

Fet said, “The 5 train still turns around on the inner loop.”

Cray-Z spat onto the tracks. “Man knows his trains.”

Light grew inside the space as the train approached, brightening the old station, bringing it briefly to life. Mayor Koch shook under Eph’s hand.

“You watch real close, now,” said Cray-Z. “No blinking!” He covered his blind eye and smiled his mostly toothless smile.

The train thundered past them, taking the turn a little faster than usual. The cars were nearly vacant inside, maybe one or two people visible through the windows, here and there a solitary straphanger. Abovegrounders just passing through.

Cray-Z gripped Eph’s forearm as the end of the train approached. “There—right there—”

In the flickering light of the passing train, Fet and Eph saw something on the rear exterior of the final car. A cluster of figures—of bodies, people—flat against the outside of the train. Clinging to it like remoras riding a steel shark.

“You see that?” exulted Cray-Z. “You see ’em all? The Other People.”

Eph shook loose of Cray-Z’s grip, taking a few steps forward away from him and Mayor Koch, the train finishing its loop and dwindling into darkness, the light leaving the tunnel like water down a drain.

Cray-Z started hustling back to his shack. “Somebody has to do something, right? You guys just decided it for me. These are the dark angels at the end of time. They’ll snatch us all if we let ’em.”

Fet took a few lumbering steps after the receding train, before stopping and looking back at Eph. “The tunnels. It’s how they get across. They can’t go over moving water, right? Not unassisted.”

Eph was right there with him. “But under the water. Nothing stops them from that.”

“Progress,” said Fet. “This is the trouble progress gets us in. What do you call it—when you figure out you can get away with shit that nobody made up a specific rule for?”

“A loophole,” said Eph.

“Exactly. This, right here?” Fet opened his arms, gesturing at their surroundings. “We just discovered one giant gaping loophole.”

The Coach

THE LUXURY COACH bus departed New Jersey’s St. Lucia’s Home for the Blind in the early afternoon, headed for an exclusive academy in Upstate New York.

The driver, with his corny stories and an entire catalog of knock-knock jokes, made the journey fun for his passengers, some sixty nervous children between the ages of seven and twelve. Their cases had been culled from emergency-room reports throughout the tristate area. These children were recently visually impaired—all had been accidentally blinded by the recent lunar occultation—and, for many, this was their first trip without a parent present.

Their scholarships, all offered and provided by the Palmer Foundation, included this orientation-like camp outing, an immersive retreat in adaptive techniques for the newly blind. Their chaperones—nine young adult graduates of St. Lucia’s—were each legally blind, meaning their central visual acuity rated 20/200 or less, though they had some residual light perception. The children in their care were all clinically NLP, or “no light perception,” meaning totally blind. The driver was the only sighted person on board.

The traffic was slow in many spots, due to the jam-ups surrounding Greater New York, but the driver kept the children entertained with riddles and banter. At other times, he narrated the ride, or described the interesting things he could see out the window, or invented details in order to make the mundane interesting. He was a longtime employee of St. Lucia’s, who didn’t mind playing the clown. He knew that one secret to unlocking the potential of these traumatized children, and opening their hearts to the challenges ahead, was to feed their imagination and involve and engage them.

“Knock-knock.”

Who’s there?

“Disguise.”

Disguise who?

“Disguise jokes are killing me.”

The stop at McDonald’s went well, all things considered, except that the Happy Meal toy was a hologram card. The driver sat apart from the group, watching the youngsters finding their French fries with tentative hands, having not yet learned to “clock” their meal for ease of consumption. At the same time, unlike the majority of blind children who were born sight-impaired, McDonald’s had visual meaning for them, and they seemed to find comfort in the smooth plastic swivel chairs and oversize drinking straws.

Back on the road, the three-hour ride stretched into double that amount of time. The chaperones led the children singing in rounds, then broadcast some audiobooks on the overhead video screens. A number of the younger children, their biological clocks thrown off by blindness, dozed on and off.

The chaperones perceived the change in light quality through the coach windows, aware of darkness falling outside. The coach moved more swiftly as they got into New York State—until all at once they felt it decelerate suddenly, enough so that stuffed animals and drink cups fell to the floor.

The coach pulled to the side and stopped.

“What is it?” asked the lead chaperone, a twenty-four-year-old assistant teacher named Joni, sitting closest to the front of the bus.

“Don’t know … something strange. Just sit tight. I’ll be right back.”