По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

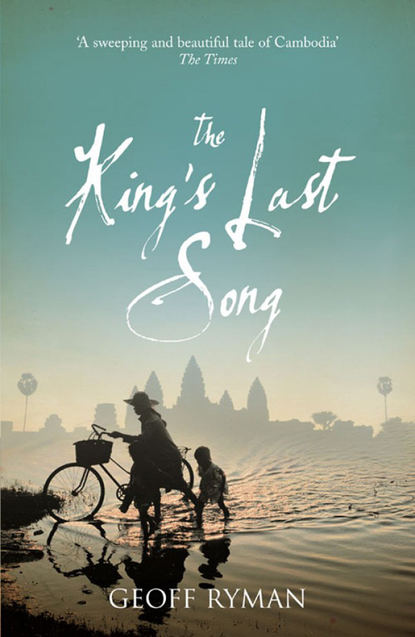

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You can call me Prince Nia.’

She chuckled. ‘You can call me Princess Nia!’

For some reason the laughter faded.

‘I hardly remember my home either,’ said Cap-Pi-Hau.

Until the day of his marriage, Cap-Pi-Hau called himself Prince Nia. When people expressed astonishment at the choice he would explain. ‘All princes are hereditary slaves.’

The day of the procession arrived.

The Sun King’s great new temple was to be consecrated.

Prince Nia stood high on the steps of an elephant platform. Ahead of him the next batch of hostage children crowded the platform, scowling at the sunlight, flicking their fly whisks.

The Prince had never stood so high off the ground. He was now level with the upper storey of the Aerial Palace. There were no walls and all the curtains were raised.

He saw servants scurrying, carrying, airing, beating – taking advantage of their mistresses’ absence to perfect the toilet of the rooms. Category girls ran with armloads of blackened flowers to throw them away. They beat cushions against each other. They shifted low bronze tables so that the floor could be wiped.

In the corners, musical instruments were carefully stood at attention, their wooden bellies gleaming. The lamp hooks screwed into the pillars were swirling bronze images of smoke or cloud-flowers. The rooms had handsome water butts of their own, with fired glazed patterns. The pillars on the upper floor were ornately carved, with images of celestial maidens, as if the rooms were already high in heaven.

He could see the lintels and the gables close up. Monsters called Makara spewed out fabulous beasts from their mouths. Gods abducted women. Brahma rode his giant goose; Krishna split a demon asura in two. Regularly recurring shapes of flames or lotus petals were embedded with glass pieces. And the roof! It was tiled with metal, armoured like a soldier’s breastplate. The metal was dull grey like a cloudy sky, smooth and streaked from rain. So many things had been kept from him!

An elephant lumbered towards them. It was old, and the howdah on its back wobbled on its loose skin.

It was not a good elephant. The howdah was functional, no carvings. The beast came close to them and coughed, and its breath smelled of dead mice.

Now the King’s elephant! Its tusks would be sheathed in gold, and the howdah would rest on a beautiful big carpet!

The children began to advance one at a time onto the elephant’s unsteady back.

And the King himself, is he blue, Nia wondered, like Vishnu? If he is the Sun Shield, is he blinding, like the sun?

Someone shoved Nia from behind, trying to push him aside. Nia thrust back and turned. It was an older, more important prince. ‘Get out of the way. I am higher rank than you.’ It was the son of the King’s nephew.

‘We all climb up and take our turn.’

At the top of the steps, a kamlaa-category slave herded them. ‘OK, come on, press in, as many as possible.’ He wore only a twist of cloth and was hot, bored, and studded with insect bites. He grabbed hold of the Prince’s shoulders and pulled him forward. Nia tossed his shoulders free. He wanted to board the howdah by himself. In the future, I will be a warrior, Nia thought; I will need to be able to do this like a warrior. He saw himself standing with one foot outside the howdah, firing his arrows.

The kamlaa peremptorily scooped him up and half-flung him onto the howdah. Prince Nia stumbled onto a girl’s heel; she elbowed him back. Nia’s face burned with shame. He heard older boys laugh at him.

Then the kamlaa said, ‘OK that’s enough, step back.’

The King’s nephew’s son tried to crowd in, but the kamlaa shoved him back. The higher prince fixed Nia with a glare and stuck his thumb through his fingers at him.

The elephant heaved itself forward, turning. Was the procession beginning? Prince Nia craned his neck to see. All he saw was embroidered backs. Nia prised the backs apart and squeezed his way through to the front. Two older boys rammed him in the ribs. ‘You are taller than me,’ Nia said. ‘You should let me see!’

The elephant came to rest, in no shade at all. They waited. Sweat trickled down the Prince’s back.

‘I need to pee,’ whispered a little girl.

Adults lay sprawled in the shade under the silk-cottons. Soldiers lay sleeping, wearing what they wore to battle, a twist of cloth and an amulet for protection. Cap-Pi-Hau scowled. Why didn’t they dress for the consecration? Their ears were sliced and lengthened, but they wore no earrings.

The musicians were worse. They had propped their standards up against the wall. A great gong slept on the ground. The men squatted, casting ivories as if in a games house. Did they not know that the King created glory through the Gods? That was why their house had a roof made of lead.

The afternoon baked and buzzed and there was not enough room to sit down. Finally someone shouted, ‘The King goes forth! The King goes forth!’

A Brahmin, his hair bundled up under a cloth tied with pearls, was being trotted forward in a palanquin.

The Brahmin shouted again. ‘Get ready, stand up! Stop sprawling about the place!’ He tried to look very important, which puffed out his cheeks and his beard, as if his nose was going to disappear under hair. The Prince laughed and clapped his hands. ‘He looks silly!’

Grand ladies stood up and arranged themselves in imitation of the lotus, pink, smiling and somehow cool. Category girls scurried forward with tapers to light their candles or pluck at and straighten the trains of threaded flower buds that hung down from the royal diadems.

The musicians tucked their ivories into their loincloths next to their genitals for luck. They shouldered up long sweeping poles that bore standards: flags that trailed in the shape of flames, or brass images of dancing Hanuman, the monkey king.

A gong sounded from behind the royal house. A gong somewhere in front replied. The tabla drums, the conches and the horns began to blare and wail and beat. Everything quickened into one swirling, rousing motion. The procession inflated, unfolded and caught the sunlight.

The footsoldiers began to march in rows of four, spears raised, feet crunching the ground in unison and sweeping off the first group of musicians along with them. A midget acrobat danced and somersaulted alongside the musicians and the children in the howdahs applauded.

Then, more graceful, the palace women swayed forward, nursing their candles behind cupped hands.

‘Oh hell!’ one of the boys yelped. ‘You stupid little civet, you’ve pissed all over my feet!’

Prince Nia burst into giggles at the idea of the noble prince having to shake pee-pee from his feet.

The boy was mean and snarled at the little girl. ‘You’ve defiled a holy day. The guards will come and peel off your skin. Your whole body will turn into one big scab.’

The little girl wailed.

Nia laughed again. ‘You’re just trying to scare her.’

Scaring a baby wasn’t much fun. Fun was telling a big boy that he was a liar when there wasn’t enough space to throw a punch. Nia turned to the little girl. ‘They won’t pull your skin off. We’re not important enough. He just thinks his feet are important.’

Nia laughed at his own joke and this time, some of the other children joined in. The older boy’s eyes went dark, and seemed to withdraw like snails into their shells.

Endure. That was the main task of a royal child.

Suddenly, at last, the elephant lurched forward. They were on their way! The Prince stood up higher, propping his thighs against the railing. He could see everything!

They rocked through the narrow passageway towards the main terrace. Nia finally saw close up the sandstone carvings of heavenly maidens, monsters, and smiling princes with swords.

They were going to leave the royal house. I’m going to see them, thought the Prince; I’m going to see the people outside!

They swayed out into the royal park.

There were the twelve towers of justice, tiny temples that stored the tall parasols. Miscreants were displayed on their steps, to show their missing toes.

The howdah dipped down and the Prince saw the faces of slave women beaming up at them. The women cheered and threw rice and held up their infants to see. No men, their men were all in the parade as soldiers.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0