History of the State of California

"After the minutes had been read, the Committee appointed to draw up an Address to the people of California, was called upon to report, and Mr. Steuart, Chairman, read the Address. Its tone and sentiment met with universal approval, and it was adopted without a dissenting voice. A resolution was then offered to pay Lieutenant Hamilton, who is now engaged in engrossing the Constitution upon parchment, the sum of $500 for his labor. This magnificent price, probably the highest ever paid for a similar service, is on a par with all things else in California. As this was their last session, the members were not disposed to find fault with it, especially when it was stated by one of them that Lieutenant Hamilton had written day and night to have it ready, and was still working upon it, though with a lame and swollen hand. The sheet for the signer's names was ready, and the Convention decided to adjourn for half an hour and then meet for the purpose of signing.

"I amused myself during the interval by walking about the town. Every body knew that the Convention was about closing, and it was generally understood that Captain Burton had loaded the guns at the fort, and would fire a salute of thirty-one guns at the proper moment. The citizens, therefore, as well as the members, were in an excited mood. Monterey never before looked so bright, so happy, so full of pleasant expectation.

"About one o'clock the Convention met again; few of the members, indeed, had left the hall. Mr. Semple, though in feeble health, called them to order, and, after having voted General Riley a salary of $10,000, and Mr. Halleck, Secretary of State, $6000 a year, from the commencement of their respective offices, they proceeded to affix their names to the completed Constitution. At this moment a signal was given; the American colors ran up the flag-staff in front of the government buildings, and streamed out on the air. A second afterward the first gun boomed from the fort, and its stirring echoes came back from one hill after another, till they were lost in the distance.

"All the native enthusiasm of Captain Sutter's Swiss blood was aroused; he was the old soldier again. He sprang from his seat, and, waving his hand around his head, as if swinging a sword, exclaimed; 'Gentlemen, this is the happiest day of my life. It makes me glad to hear those cannon: they remind me of the time when I was a soldier. Yes, I am glad to hear them – this is a great day for California!' Then, recollecting himself, he sat down, the tears streaming from his eyes. The members with one accord, gave three tumultuous cheers, which were heard from one end of the town to the other. As the signing went on, gun followed gun from the fort, the echoes reverberating grandly around the bay, till finally, as the loud ring of the thirty-first was heard, there was a shout: 'That's for California!' and every one joined in giving three times three for the new star added to our Confederation.

"There was one handsome act I must not omit to mention. The captain of the English bark Volunteer, of Sidney, Australia, lying in the harbor, sent on shore in the morning for an American flag. When the first gun was heard, a line of colors ran fluttering up to the spars, the stars and stripes flying triumphantly from the main-top. The compliment was the more marked, as some of the American vessels neglected to give any token of recognition to the event of the day.

"The Constitution having been signed and the Convention dissolved, the members proceeded in a body to the house of General Riley. The visit was evidently unexpected by the old veteran. When he made his appearance, Captain Sutter stepped forward, and having shaken him by the hand, drew himself into an erect attitude, raised one hand to his breast as if he were making a report to his commanding officer on the field of battle, and addressed him as follows:

"'General: I have been appointed by the delegates, elected by the people of California to form a Constitution, to address you in their names and in behalf of the whole people of California, and express the thanks of the Convention for the aid and coöperation they have received from you in the discharge of the responsible duty of creating a State government. And, sir, the Convention, as you will perceive from the official records, duly appreciates the great and important services you have rendered to our common country, and especially to the people of California, and entertains the confident belief that you will receive from the whole of the people of the United States, when you retire from your official duties here, that verdict so grateful to the heart of the patriot: 'Well done, thou good and faithful servant.'

"General Riley was visibly affected by this mark of respect, no less appropriate than well deserved on his part. The tears in his eyes, and the plain, blunt sincerity of his voice and manner, went to the heart of every one present. 'Gentlemen,' he said, 'I never made a speech in my life. I am a soldier – but I can feel; and I do feel deeply the honor you have this day conferred upon me. Gentlemen, this is a prouder day to me than that on which my soldiers cheered me on the field of Contreras. I thank you all from my heart. I am satisfied now that the people have done right in selecting delegates to frame a Constitution. They have chosen a body of men upon whom our country may look with pride; you have framed a Constitution worthy of California. And I have no fear for California while her people choose their representatives so wisely. Gentlemen, I congratulate you upon the successful conclusion of your arduous labors; and I wish you all happiness and prosperity.'

"The General was here interrupted with three hearty cheers which the members gave him, as Governor of California, followed by three more, 'as a gallant soldier, and worthy of his country's glory.' He then concluded in the following words: 'I have but one thing to add, gentlemen, and that is, that my success in the affairs of California is mainly owing to the efficient aid rendered me by Captain Halleck, the Secretary of State. He has stood by me in all emergencies. To him I have always appealed when at a loss myself; and he has never failed me.'

"This recognition of Captain Halleck's talents and the signal service he has rendered to our authorities here, since the conquest, was peculiarly just and appropriate. It was so felt by the members, and they responded with equal warmth of feeling by giving three enthusiastic cheers for the Secretary of State. They then took their leave, many of them being anxious to start this afternoon for their various places of residence. All were in a happy and satisfied mood, and none less so than the native members. Pedrorena declared that this was the most fortunate day in the history of California. Even Carillo, in the beginning one of our most zealous opponents, displayed a genuine zeal for the Constitution, which he helped to frame under the laws of our republic."

The elections for the various officers under the new Constitution took place on the 13th of November, 1849. Peter H. Burnett was chosen Governor, and John McDougall, Lieutenant-Governor. George W. Wright and Edward Gilbert were chosen to fill the posts of representatives in Congress. The first State Legislature met at the capital, the pueblo de San José, on the 15th of December, and elected John C. Fremont and Wm. M. Gwin, Senators to Congress. Every branch of the civil government went at once into operation, and admission into the Union as a State seems all that is necessary to complete the settlement of affairs in California.

CHAPTER X

POPULATION, CLIMATE, PRODUCTIONS, &CWith regard to the population, climate, soil, productions, &c., we extract from Mr. King's Report, as giving the most reliable and complete information.

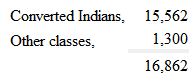

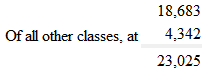

"Humboldt, in his 'Essay on New Spain,' states the population of Upper California, in 1802, to have consisted of

"Alexander Forbes, in his 'History of Upper and Lower California,' published in London, in 1839, states the number of converted Indians in the former to have been, in 1831,

"He expresses the opinion that this number had not varied much up to 1835, and the probability is, there was very little increase in the white population until the emigrants from the United States began to enter the country in 1838.

"They increased from year to year, so that, in 1846, Colonel Fremont had little difficulty in calling to his standard some five hundred fighting men.

"At the close of the war with Mexico, it was supposed that there were, including discharged volunteers, from ten to fifteen thousand Americans and Californians, exclusive of converted Indians, in the territory. The immigration of American citizens in 1849, up to the 1st of January last, was estimated at eighty thousand – of foreigners, twenty thousand.

"The population of California may, therefore, be safely set down at 115,000 at the commencement of the present year.

"It is quite impossible to form any thing like an accurate estimate of the number of Indians in the territory. Since the commencement of the war, and especially since the discovery of gold in the mountains, their numbers at the missions, and in the valleys near the coast, have very much diminished. In fact, the whole race seems to be rapidly disappearing.

"The remains of a vast number of villages in all the valleys of the Sierra Nevada, and among the foot-hills of that range of mountains, show that at no distant day there must have been a numerous population, where there is not now an Indian to be seen. There are a few still retained in the service of the old Californians, but these do not amount to more than a few thousand in the whole territory. It is said there are large numbers of them in the mountains and valleys about the head-waters of the San Joaquin, along the western base of the Sierra, and in the northern part of the territory, and that they are hostile. A number of Americans were killed by them during the last summer, in attempting to penetrate high up the rivers in search of gold; they also drove one or two parties from Trinity River. They have, in several instances, attacked parties coming from or returning to Oregon, in the section of country which the lamented Captain Warner was examining when he was killed.

"It is quite impossible to form any estimate of the number of these mountain Indians. Some suppose there are as many as three hundred thousand in the territory, but I should not be inclined to believe that there can be one-third of that number. It is quite evident that they are hostile, and that they ought to be chastised for the murders already committed.

"The small bands with whom I met, scattered through the lower portions of the foot-hills of the Sierra, and in the valleys between them and the coast, seemed to be almost the lowest grade of human beings. They live chiefly on acorns, roots, insects, and the kernel of the pine burr; occasionally, they catch fish and game. They use the bow and arrow, but are said to be too lazy and effeminate to make successful hunters. They do not appear to have the slightest inclination to cultivate the soil, nor do they even attempt it – as far as I could obtain information – except when they are induced to enter the service of the white inhabitants. They have never pretended to hold any interest in the soil, nor have they been treated by the Spanish or American immigrants as possessing any.

"The Mexican government never treated with them for the purchase of land, or the relinquishment of any claim to it whatever. They are lazy, idle to the last degree, and, although they are said to be willing to give their services to any one who will provide them with blankets, beef, and bread, it is with much difficulty they can be made to perform labor enough to reward their employers for these very limited means of comfort.

"Formerly, at the missions, those who were brought up and instructed by the priests made very good servants. Many of these now attached to families seem to be faithful and intelligent. But those who are at all in a wild and uncultivated state are most degraded objects of filth and idleness.

"It is possible that government might, by collecting them together, teach them, in some degree, the arts and habits of civilization; but, if we may judge of the future from the past, they will disappear from the face of the earth as the settlements of the whites extend over the country. A very considerable military force will be necessary, however, to protect the emigrants in the northern and southern portions of the territory."

So much for the population of California at the commencement of the present year, (1850.) By its close, it is highly probable, the number will reach two hundred thousand, exclusive of the Indians. Such a population, composed, for the most part, of those who are impregnated with the active, progressive spirit of the American people, will undoubtedly conduct California to a brilliant position among the stars of the republic. With regard to the climate of the country, various conflicting statements have been promulgated, which arises from the visits of those who make the statements having been made to different portions of the country, and stating the climate of a portion as the climate of the whole. Mr. King's Report furnishes the most accurate account of the changes of the temperature, and the state of the atmosphere throughout the year, together with an explanation of their causes. He says —

"I come now to consider the climate. The climate of California is so remarkable in its periodical changes, and for the long continuance of the wet and dry seasons, dividing, as they do, the year into about two equal parts, which have a most peculiar influence on the labor applied to agriculture and the products of the soil, and, in fact, connect themselves so inseparably with all the interests of the country, that I deem it proper briefly to mention the causes which produce these changes, and which, it will be seen, as this report proceeds, must exercise a controlling influence on the commercial prosperity and resources of the country.

"It is a well-established theory, that the currents of air under which the earth passes in its diurnal revolutions, follow the line of the sun's greatest attraction. These currents of air are drawn towards this line from great distances on each side of it; and, as the earth revolves from west to east, they blow from north-east and south-east, meeting, and, of course, causing a calm, on the line.

"Thus, when the sun is directly, in common parlance, over the equator, in the month of March, these currents of air blow from some distance north of the Tropic of Cancer, and south of the Tropic of Capricorn, in an oblique direction towards this line of the sun's greatest attraction, and forming what are known as the north-east and south-east trade winds.

"As the earth, in its path round the sun, gradually brings the line of attraction north, in summer, these currents of air are carried with it; so that about the middle of May the current from the north-east has extended as far as the 38th or 39th degree of north latitude, and by the twentieth of June, the period of the sun's greatest northern inclination, to the northern portions of California and the southern section of Oregon.

"These north-east winds, in their progress across the continent, towards the Pacific Ocean, pass over the snow-capped ridges of the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, and are, of course, deprived of all the moisture which can be extracted from them by the low temperature of those regions of eternal snow, and consequently no moisture can be precipitated from them, in the form of dew or rain, in a higher temperature than that to which they have been subjected. They, therefore, pass over the hills and plains of California, where the temperature is very high in summer, in a very dry state; and, so far from being charged with moisture, they absorb, like a sponge, all that the atmosphere and surface of the earth can yield, until both become, apparently, perfectly dry.

"This process commences, as I have said, when the line of the sun's greatest attraction comes north in summer, bringing with it these vast atmospheric movements, and, on their approach, produce the dry season in California; which, governed by these laws, continues until some time after the sun repasses the Equator in September, when, about the middle of November, the climate being relieved from these north-east currents of air, the south-west winds set in from the ocean charged with moisture – the rains commence and continue to fall, not constantly, as some persons have represented, but with sufficient frequency to designate the period of their continuance, from about the middle of November until the middle of May, in the latitude of San Francisco, as the wet season.

"It follows, as a matter of course, that the dry season commences first, and continues longest in the southern portions of the territory, and that the climate of the northern part is influenced in a much less degree, by the causes which I have mentioned, than any other section of the country. Consequently, we find that, as low down as latitude 39°, rains are sufficiently frequent in summer to render irrigation quite unnecessary to the perfect maturity of any crop which is suited to the soil and climate.

"There is an extensive ocean current of cold water, which comes from the northern regions of the Pacific, or, perhaps, from the Arctic, and flows along the coast of California. It comes charged with, and emits in its progress, cold air, which appears in the form of fog when it comes in contact with a higher temperature on the American coast, as the gulf-stream of the Atlantic exhales vapor when it meets, in any part of its progress, a lower temperature. This current has not been surveyed, and, therefore, its source, temperature, velocity, width, and course, have not been accurately ascertained.

"It is believed, by Lieutenant Maury, on what he considers sufficient evidence – and no higher authority can be cited – that this current comes from the coasts of China and Japan, flows northwardly to the peninsula of Kamtschatka, and, making a circuit to the eastward, strikes the American coast in about latitude 41° or 42°. It passes thence southwardly, and finally loses itself in the tropics.

"Below latitude thirty-nine, and west of the foot-hills of the Sierra Nevada, the forests of California are limited to some scattering groves of oak in the valleys and along the borders of the streams, and of red wood on the ridges and in the gorges of the hills – sometimes extending into the plains. Some of the hills are covered with dwarf shrubs, which may be used as fuel. With these exceptions, the whole territory presents a surface without trees or shrubbery. It is covered, however, with various species of grass, and, for many miles from the coast, with wild oats, which, in the valleys, grow most luxuriantly. These grasses and oats mature and ripen early in the dry season, and soon cease to protect the soil from the scorching rays of the sun. As the summer advances, the moisture in the atmosphere and the earth to a considerable depth, soon becomes exhausted; and the radiation of heat, from the extensive naked plains and hill-sides, is very great.

"The cold, dry currents of air from the north-east, after passing the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, descend to the Pacific, and absorb the moisture of the atmosphere, to a great distance from the land. The cold air from the mountains, and that which accompanies the great ocean current from the north-west, thus become united; and vast banks of fog are generated, which, when driven by the wind has a penetrating, or cutting, effect on the human skin, much more uncomfortable than would be felt in the humid atmosphere of the Atlantic, at a much lower temperature.

"As the sun rises from day to day, week after week, and month after month, in unclouded brightness during the dry season, and pours down its unbroken rays on the dry, unprotected surface of the country, the heat becomes so much greater inland than it is on the ocean, that an under-current of cold air, bringing the fog with it, rushes over the coast range of hills, and through their numerous passes, towards the interior.

"Every day, as the heat, inland, attains a sufficient temperature, the cold, dry wind from the ocean commences to blow. This is usually from eleven to one o'clock: and, as the day advances, the wind increases and continues to blow till late at night. When the vacuum is filled, or the equilibrium of the atmosphere restored, the wind ceases; a perfect calm prevails until about the same hour the following day, when the same process commences and progresses as before; and these phenomena are of daily occurrence, with few exceptions, throughout the dry season.

"These cold winds and fogs render the climate at San Francisco, and all along the coast of California, except the extreme southern portion of it, probably more uncomfortable, to those not accustomed to it, in summer than in winter.

"A few miles inland, where the heat of the sun modifies and softens the wind from the ocean, the climate is moderate and delightful. The heat, in the middle of the day, is not so great as to retard labor or render exercise in the open air uncomfortable. The nights are cool and pleasant. This description of climate prevails in all the valleys along the coast range, and extends throughout the country, north and south, as far eastward as the valley of the Sacramento and San Joaquin. In this vast plain, the sea-breeze loses its influence, and the degree of heat in the middle of the day, during the summer months, is much greater than is known on the Atlantic coast in the same latitudes. It is dry, however, and probably not more oppressive. On the foot-hills of the Sierra Nevada, and especially in the deep ravines of the streams, the thermometer frequently ranges from 110° to 115° in the shade, during three or four hours of the day, say from eleven until three o'clock. In the evening, as the sun declines, the radiation of heat ceases. The cool, dry atmosphere from the mountains spreads over the whole country, and renders the nights cool and invigorating.

"I have been kindly furnished, by Surgeon-General Lawson, U.S. Army, with thermometrical observations, taken at the following places in California, viz: At San Francisco, by Assistant-Surgeon W. C. Parker, for six months, embracing the last quarter of 1847 and the first quarter of 1848. The monthly mean temperature was as follows: October, 57°; November, 49°; December, 50°; January, 49°; February, 50°; March, 51°.

"At Monterey, in latitude 36° 38' north and longitude 121° west, on the coast, about one degree and a half south of San Francisco, by Assistant-Surgeon W. S. King, for seven months, from May to November inclusive. The monthly mean temperature was: May, 56°; June, 59°; July, 62°; August, 59°; September, 58°; October, 60°; November, 56°.

"At Los Angeles, latitude 34° 7', longitude west 118° 7', by Assistant-Surgeon John S. Griffin, for ten months, from June, 1847, to March, 1848, inclusive. The monthly mean temperature was: June, 73°; July, 74°; August, 75°; September, 75°; October, 69°; November, 59°; December, 60°; January, 58°; February, 55°; March, 58°. This place is about forty miles from the coast.

"At San Diego, latitude 32° 45', longitude west 117° 11', by Assistant-Surgeon J. D. Summers, for the following three months of 1849, viz: July, monthly mean temperature, 73°; August 75°; September, 70°.

"At Suttersville, on the Sacramento River, latitude 38° 32' north, longitude west 121° 34', by Assistant-Surgeon R. Murray, for the following months of 1849: July, monthly mean temperature, 73°; August, 70°; September, 65°; October, 65°.

"These observations show a remarkably high temperature at San Francisco during the six months from October to March inclusive; a variation of only eight degrees in the monthly mean, and a mean temperature for the six months of 51 degrees.

"At Monterey, we find the mean monthly temperature of the seven months to have been 58°. If we take the three summer months, the mean heat was 60°. The mean of the three winter months was a little over 49°; showing a mean difference, on that part of the coast, of only 11° between summer and winter.