Stones of the Temple; Or, Lessons from the Fabric and Furniture of the Church

At the conclusion of the service Mr. Acres met the Vicar in the vestry.

"I should like," said he, "to go with you to see our poor old friend once more."

"It will probably be the last time," replied the Vicar, "for he was evidently sinking when I saw him before service. I told little Harry to go up to him as soon as we had sung the last hymn."

Both went up together. The Vicar was not mistaken. Calm and peaceful, without a line of care or pain, there lay the placid face, and the eyes were closed in the last, long sleep. One hand lay motionless upon the bed, grasped by his little grandson, who was kneeling beside him, still robed in the snow-white surplice with which he had recently left the choir.

"Poor little fellow!" said the Vicar; "I will keep my promise to the old man. He shall not be left without a friend, though his best is gone."

But Mr. Acres saw that the little hands were white as the aged hand they clasped.

"He's with a better Friend now, my dear Vicar," said he, "than this earth can give him. We shall hear his sweet voice no more in our choir here; he has gone to join the choir of angels in a nobler temple than ours."

Old Matthew's words were true; the loving little heart was broken. The old oak had fallen, and crushed the tender sapling as it fell221. On the morning of Trinity Sunday, there stood under the old yew-tree of St. Catherine's churchyard, three little stone crosses side-by-side, where but one had been before.

THE END1

In some parts of Devonshire and Cornwall, Lich-Gates are called "Trim-Trams." The origin of this word is not easy to determine; it is probably only a nickname.

2

Anglo-Saxon, lic, – a dead body. In Germany the word leiche has doubtless the same original; it is still used to signify a corpse or funeral. The German leichengang has precisely the same meaning as our Lich-Gate.

3

It is stated in Britton's Antiquities that there was formerly a Lych-Gate in a lane called Lych-lane in Gloucester, where the body of Edward II. rested on its way to burial in the Cathedral.

4

A Lyke-wake dirge: —

"This ae nighte, this ae nighte,Every nighte and alle;Fire and sleete, and candle lighte,And Christe receive theye saule."(Scott's "Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.")5

On the Lich-Gate at Bray, Berks, is the date 1448; but there are very few examples so early.

6

The following are among the most interesting of the ancient Lich-Gates still remaining: – Beckenham, Lincolnshire; Berry-Harbor, Devonshire; Birstal, York; Bromsgrove, Worcestershire; Burnside, Westmoreland; Compton, Berkshire; Garsington, Oxon; Tawstock, Devonshire; West Wickham, Kent; and Worth, Sussex. The construction of the gate at Burnside is very curious, and Tawstock Lich-Gate possesses peculiar features of interest, which are noticed in the next Chapter. One of the finest Lich-Gates was at Arundel, in Surrey, but it has been removed, and is now the Church Porch.

7

St. John xi. 25. The first words of the Burial Office, said by the Priest at the entrance to the Churchyard.

8

A very interesting paper on Lich-Gates, in the "Clerical Journal," affords much information on this subject. Over the gate at Bray are "two chambers, connected with an ancient charitable bequest."

9

This chamber was formerly called the Chapel of the Holy Rood.

10

The custom of distributing "cakes and ale" at the churchyard on the occasion of funerals in Scotland, has been but very recently given up. Dean Ramsey, in his interesting "anecdotes," has informed us that at the burial of the Chief of a clan, many thousands would sometimes assemble, and not unfrequently the funeral would end in a disgraceful riot.

11

In Cornwall the now common practice of placing a wreath of white flowers on the coffin is a very ancient and still prevailing usage.

12

Consecrated Bishop of Exeter A.D. 1598.

13

These crosses were erected at the following places: – Lincoln, Northampton, Dunstable, St. Alban's, Waltham, Stratford, Cheapside, Blackfriars, and Charing; those at Waltham and Northampton alone remain. The statue of King Charles now stands where the Charing ("Chère Reine") Cross formerly stood.

14

In a churchyard in Oxfordshire, a large altar-tomb, surrounded by iron railings, occupying a space of ground in which at least thirty persons might be buried, covers the grave of an infant of three months.

The erection of these masses of stone without restraint would make our churchyards only the burial-places of the rich, and would soon entirely exclude the poor from a place in them; whereas the poor have an equal claim with the rich to be buried there, and when buried, the same title to respect and protection.

15

The urns which are placed upon so many tombs in our cemeteries and churchyards, unless they have reference to the heathen custom of burning the dead, and placing the ashes in funeral urns, can have no meaning at all. We moreover not unfrequently see a gilded flame issuing from these urns, and here of course the reference is most clearly marked. The Christian custom of burying the dead, which we practise in imitation of the entombment of Christ, dates from the earliest history of man; and as well from the Old as the New Testament we learn that it has ever been followed by those who professed to obey the Divine will. The first grave of which we have any account was the grave of Sarah, Abraham's wife (Gen. xxiii. 19), and the first grave-stone was that over the burial-place of Rachel, Jacob's wife (Gen. xlix. 31).

16

There are comparatively but few churchyard grave-stones more than 250 years old, and probably there are very few of an earlier date but have engraved upon them the sign of the Cross. There are two very ancient grave-stones of this character, having also heads carved upon them, in the churchyard of Silchester. It is likely that the old churchyard crosses were often mortuary memorials. Probably there is hardly an old churchyard but has, at some time, been adorned with its churchyard cross; in most cases, some remains of this most appropriate and beautiful ornament still exist, and doubtless is often older than the churchyard as a place of Christian burial. In many places this cross has been lately restored to its proper place, near to the Lich-Gate. "Let a handsome churchyard cross be erected in every churchyard." – Institutions of the Bishop of Winchester, A.D. 1229.

17

The interesting custom of placing natural flowers and wreaths upon graves, is in every respect preferable to that which we see practised in Continental burial-grounds, where the graves are often covered with immortelles, vases of gaudy artificial flowers, images, &c. We have seen as many as fifty wreaths of artificial flowers and tinselled paper, in every stage of decomposition, over one grave in the cemetery of Père la Chaise, in Paris. In Wales it is a more general practice than in England, to adorn the graves with fresh flowers on Easter Day.

18

This story is true of a parish in Monmouthshire.

19

It is comparatively seldom that any other than the funerals of the poor take place on Sunday, and the reason commonly assigned is – that it is the only day on which their friends can attend. In one, at least, of the large metropolitan cemeteries, exclusively used as a burial-place for the rich, no funerals ever take place on a Sunday.

20

Let us hope that the time is near when this objectionable and unsightly appendage will be banished from our funeral processions. The late Mr. Charles Dickens, in his will, forbad the wearing of hat-bands at his funeral.

21

"In several parts of the north of England, when a funeral takes place, a basin full of sprigs of boxwood is placed at the door of the house from which the coffin is taken up, and each person who attends the funeral ordinarily takes a sprig of the boxwood and throws it into the grave of the deceased." —Wordsworth (Notes, Excursion, p. 87).

22

Great care was taken by the medieval architects to make the porches of their churches as beautiful as possible. During some periods, especially the Norman, they seem to have bestowed more labour upon them than upon any other portion of the building. Both externally and internally they were richly decorated, and often abounded in emblematic tracery.

23

"The custom formerly was for the couple, who were to enter upon this holy state, to be placed at the church door, where the priest was used to join their hands, and perform the greater part of the matrimonial office. It was here the husband endowed his wife with the dowry before contracted for." —Wheatley. In a few church porches there are, or have been, galleries, which seem to have been intended to accommodate a choir for these and other festive occasions.

24

"The porch of the church was anciently used for the performance of several religious ceremonies appertaining to Baptism, Matrimony, and the solemn commemoration of Christ's Passion in Holy Week," &c. —Brandon's Gothic Architecture. The Office for the Churching of Women also used to be said at the church porch.

25

As our Commination Service declares, persons who stood convicted of notorious sins were formerly put to open penance. The punishment frequently inflicted was – that they should stand at the church door, clothed in a white sheet, and holding a candle in each hand, during the assembling and departure of the congregation on a Sunday morning. The old parish clerk of Walton-on-Thames, Surrey, remembers, when a boy, seeing a Jew perform this penance in Walton church.

26

"Formerly persons used to assemble in the church porch for civil purposes." —Brandon.

27

"At a very early period, persons of rank or of eminent piety were allowed to be buried in the porch. Subsequently, interments were permitted within the church, but by the Canons of King Edgar it was ordered that this privilege should be granted to none but good and religious men." —Parker's Glossary.

28

The parvise is to be found over church porches in all parts of England. It is more common in early English than in Norman architecture, and very frequently to be found in churches of the Decorated and Perpendicular periods. Probably the largest parvise in England is at Bishop's-Cleeve, near Cheltenham. There are interesting specimens at Bridport, Bishop's Auckland, Ampthill, Finedon, Cirencester, Grantham, Martley, Fotheringay, Sherborne, St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, Stanwick, Outwell, and St. Peter's-in-the-East, Oxford. In a few instances there are two parvises, one over the north and one over the south porch, as at Wellingborough. In some cases, as at Martley, Worcestershire, the upper moulding of the original Norman doorway has been concealed by the parvise of later architecture.

29

"The name was formerly given to a favourite apartment, as at Leckingfield, Yorkshire. 'A little studying chamber, caullid paradise.' (Leland's Itinerary.)" —Glossary of Architecture.

30

The room may have been the residence of one or more of the ordinary priests of the church, or perhaps only a study for them (see previous note), or it may have been occupied by an anchorite or hermit, or by a chantry priest. Rooms for these several purposes are also not unfrequently to be found over the vestry, as at Cropredy, near Banbury, and at Staindrop, Durham.

31

Fire-places are of frequent occurrence in these chambers; many of them are coeval with the porch, but others appear to have been erected at a later date.

32

At Hawkhurst, Kent, the porch-chamber is called the treasury. At St. Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, the room over the grand north porch, in which are the remains of the chests in which Chatterton professed to find the manuscripts attributed to Rowley, was at one time known as the treasury house.

33

"The chamber over the porch was generally used for the keeping of books and records belonging to the church. Such an appendage was added to many churches in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries; and some of these old libraries still remain with their books fastened to shelves or desks by small chains." —Brandon's Gothic Architecture.

Over the porch at Finedon (of which we give an engraving) is a parvise in which is contained a valuable library of about 1000 volumes, placed there by Sir John English Dolben, Bart., A.D. 1788. At St. Peter's-in-the-East, Oxford, and many other places, are similar libraries.

34

These were probably small chantries. It is comparatively seldom that any vestige of the altar remains; but the credence and piscina – certain proofs of the previous existence of the altar – are very commonly found.

35

"The custom of teaching children in the porch is of very early origin; it is distinctly mentioned by Matthew Paris in the time of Henry III." —Glossary of Architecture.

After the reigns of Henry VIII. and Edward VI., in which reigns all chantries were suppressed, the children were promoted from the porch to the parvise.

36

"Above the groining of the porch is a parvise, accessible by a turret-stair, having two Norman window-openings, unglazed, and a straight-gabled niche between them on the outside. In former days this chamber was constantly inhabited by one of the sextons, who acted as a watchman, but since the restoration of the church it has been disused." —Harston's Handbook of Sherborne Abbey.

In the church accounts of St. Peter's-in-the-East, Oxford, A.D. 1488, there is a charge for a "key to clerk's chamber." This no doubt referred to the parvise.

37

As, a few years ago, at Headcorn in Kent.

38

There was frequently, but not always, a window or opening from the room into the church; and it would seem that it was so placed to enable the occupant of the room to keep a watchful eye over the interior of the church, and not for any devotional exercise connected with the altar, as we never find this window directed obliquely to wards the altar, as is commonly the case with windows opening from the vestry, or chamber above the vestry, into the church.

39

Many porches seem originally not to have had doors, but marks exist which indicate that barriers to keep out cattle were used.

40

It is composed of lamp-black, bees'-wax, and tallow, and is commonly used by shoemakers to give a black polish to the heels of boots.

41

These superstitions existed a few years since in connexion with an old incised slab in the chancel of Christ Church, Caerleon.

42

"In the year 1657, the adherents of a Preacher of the name of Cam obtained the grant of the chancel of the Holy Trinity Church, Hull, from the council of state under the Protectorate, and whilst the mob without were burning the surplice and the Prayer Book, those within were tearing the brasses from the grave-stones." —History of Kingston-upon-Hull.

s. d."1644, April 8th, paid to Master Dowson, that came with the troopers to our church, about the taking down of images and brasses off stones

"1644, paid, that day, to others, for taking up the brasses of grave-stones before the Officer Dowson came

– Churchwarden's accounts; Walberswich, Suffolk.

"This William Dowing (Dowson), it appears, kept a journal of his ecclesiastical exploits. With reference to the Church of St. Edward's, Cambridge, he says, —

"'1643, Jan. 1, Edward's Parish, we digged up the steps, and broke down 40 pictures, and took off ten superstitious inscriptions.'

"Mr. Cole, in his MSS., observes, —

"'From this last entry we may clearly see to whom we are obliged for the dismantling of almost all the grave-stones that had brasses on them, both in town and country; a sacrilegious, sanctified rascal, that was afraid, or too proud, to call it St. Edward's Church, but not ashamed to rob the dead of their honours, and the church of its ornaments. – W. C.'" —Burn's Parish Registers.

43

The very interesting brasses in Chartham Church, Kent, were found a few years since as here described, by the present rector, and replaced by him on the chancel pavement.

44

"Manual of Monumental Brasses," vol. i. p. 34.

45

"If any one will lay the portrait of Lord Bristol (in Mr. Gage Rokewode's Thingoe Hundred) by the side of the sepulchral brass of the Abbess of Elstow (from whom he is collaterally descended) figured in Fisher's Bedfordshire Antiquities, he cannot but be struck by the strong likeness between the two faces. This is valuable evidence on the disputed point whether portraits were attempted in sepulchral brasses." —Notes and Queries.

46

See page 77.

47

See page 85. [The engravings of sepulchral brasses and of stained glass windows are kindly supplied by the Editor of the Penny Post.]

48

See page 67.

49

Hamlet, Act i. Sc. 3.

50

Monumental slabs of this description are most common on the pavement of churches in the midland counties.

51

This is the case in Ely Cathedral.

52

At Bawsey, Lynn; Droitwich; Great Malvern; and recently near Smithfield, London, when excavating for the subterranean railway.

53

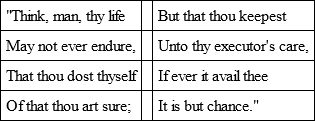

Thus translated in the Gentleman's Magazine for October, 1833: —

54

"Anno 1210. Let the Abbot of Beaubec (in Normandy), who has for a long time allowed his monk to construct, for persons who do not belong to the order, pavements, which exhibit levity and curiosity, be in slight penance for three days, the last of them on bread and water; and let the monk be recalled before the feast of All Saints, and never again be lent, excepting to persons of our order, with whom let him not presume to construct pavements which do not extend the dignity of the order." – Martini's Thesaurus Anecdotorum. – Extracted from Oldham's "Irish Pavement Tiles."

55

Specially in Normandy, where they are occasionally found under trefoil canopies, resembling our sepulchral brasses.

56

Some excellent coloured engravings for cottage walls, of a large size, have been published by Messrs. Remington, under the direction of the Rev. J. W. Burgon, of Oriel College, Oxford. Others, both large and small, suitable for this purpose, are published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, and also by several other publishers.

57

These wall paintings exist (or did till recently) on the outside of a church at High Wycombe. They are curious, and very grotesque; no doubt, however, in their day they have served a good and useful purpose.

58

These mural paintings still remain, as here described, on the north wall of the chancel of Chalgrove Church, Oxon. There are also on the east and south walls of the chancel of the same church, many other paintings possessing great interest.

59

A very interesting mural painting, of which the above is a copy, has been lately discovered in a recess in the north wall of the nave of Bedfont Church. The colour is exceedingly rich and well preserved. The painting measures 4 ft. 6 in. by 4 ft., and is supposed to be of the thirteenth century. It represents the Last Judgment. Our Lord is sitting on His Throne, showing the five wounds. On the right hand is an angel showing the Cross, on the left an angel with a spear. Four nails are represented near the head of our Lord. In the lower part of the painting are two angels holding trumpets, and below them three persons rising out of the tomb.

It is probable that the interior of almost every old church in the country has at some time been decorated with wall-paintings – very many of them have been brought to light in recent works of church restoration. The favourite subjects were representations of Heaven and Hell, and of the Day of Judgment. In many cathedrals and some parish churches the Dance of Death was painted on the walls. This was one of the most popular religious plays about four centuries ago.

60

No doubt the earliest church walls were made of wood. Greenstead Church, in Essex, affords a most interesting example of these old wooden walls.

61

Roman bricks are generally easy to be distinguished from others by their colour and shape. They were not all made in moulds of the same size, as we now make bricks, and on this account we find them to vary much in size and form.

62

As at Crowmarsh, Oxfordshire, of which an engraving is given.

63

At Godmersham, Kent.

64

It is certain that many of the splendid yew-trees in our old churchyards are far older than the churches themselves. And it is more than probable that in many instances they mark the places where heathen rites were once celebrated. It was natural for our Christian forefathers to select these spots as places of worship, since, being held sacred by the heathen people around them, they would be regarded by them with reverence and respect, and thus the cross which they reared, and the dead which they buried beneath the wide-spreading branches of these old trees would be preserved from desecration.

65

These styles are now frequently called first, second, and third pointed.

66

"The glass windows in a church are Holy Scriptures, which expel the wind and the rain, that is, all things hurtful, but transmit the light of the True Sun, that is, God, into the hearts of the faithful. These are wider within than without, because the mystical sense is the more ample, and precedeth the literal meaning. Also, by the windows the senses of the body are signified: which ought to be shut to the vanities of this world, and open to receive with all freedom spiritual gifts. By the lattice-work of the windows, we understand the Prophets or other obscure teachers of the Church Militant: in which windows there are often two shafts, signifying the two precepts of charity, or because the Apostles were sent out to preach two and two." —Durandus on Symbolism.

67

Stained glass is said to have been first used in churches in the twelfth century. Windows were at first filled with thin slices of talc or alabaster, or sometimes vellum. As the monks spent much time in illuminating their vellum MSS., it has been thought likely that they also painted on the vellum used in the windows of their monasteries, and that afterwards, on the introduction of glass, their vellum illuminations suggested their glass painting.

68

At Brabourne, Kent, is a Norman window filled with stained glass of the period, which is still quite perfect.

69

"One who calls himself John Dowsing, and, by virtue of a pretended commission, goes about ye country like a Bedlam, breaking glasse windows, having battered and beaten downe all our painted glasse, not only in our Chappels, but (contrary to order) in our Publique Schools, Colledge Halls, Libraries, and Chambers." – Berwick's Querela Cantabrigiensis.