По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

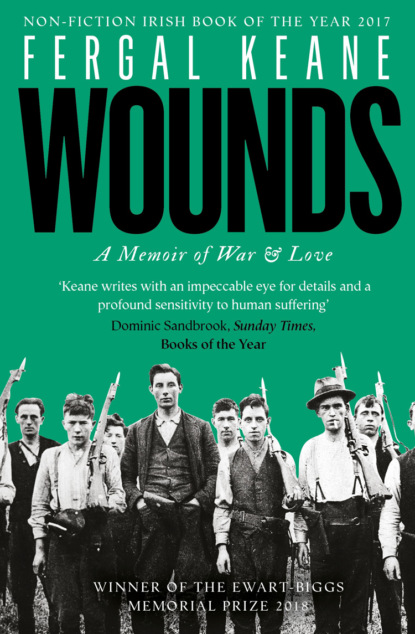

Wounds: A Memoir of War and Love

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#u60540a93-1119-515e-a380-83f97fb31654)

Prologue

We Killed All Mankind (#u60540a93-1119-515e-a380-83f97fb31654)

His manner was that the heads of all those (of what sort so ever they were) which were killed in the day, should be cut off from their bodies, and brought to the place where he encamped at night: and should there be laid on the ground, by each side of the way leading into his own tent: so that none could come into his tent for any cause, but commonly he must pass through a lane of heads … and yet did it bring great terror to the people when they saw the heads of their dead fathers, brothers, children, kinsfolk, and friends lie on the ground before their faces, as they came to speak with the said Colonel.

Thomas Churchyard, A Generall Rehearsall of Warres, 1579

I

This is the story of my grandmother Hannah Purtill, who was a rebel, and her brother Mick and his friend Con Brosnan, and how they took up guns to fight the British Empire and create an independent Ireland. And it is the story of another Irishman, Tobias O’Sullivan, who fought against them because he believed it was his duty to uphold the law of his country. It is the story too of the breaking of bonds and of civil war and of how the wounds of the past shaped the island on which I grew up. Many thousands of people took part in the War of Independence and the Civil War that followed. The story of my own family is one that might differ in some details but is shared by numerous other Irish families. They may have taken different sides but all were changed in some way, and lived in a new state defined by the costs of violence. I have spent much of my life trying to understand why people will kill for a cause and how the act of killing reverberates through the generations. This book is, in part, an attempt to understand my own obsession with war.

It starts in my grandmother’s house in the north Kerry town of Listowel, in the middle of the 1960s.

The house is asleep. My brother and sister are in beds at the other side of the room. My mother is in the room across the landing, next to the door leading up into the attic where cracked uncle Dan once lived among the cobwebs and the crows. The last drinkers have left Alla Sheehy’s next door. His wife Nora Mai is sweeping the floor. She will be muttering, drawing hard on a cigarette, cursing the hour and the work, under the eternal gaze of the stuffed fox on the counter. A Garda will pass soon on his rounds, his ear alert for the murmur of secret drinkers. There are several dozen pubs in Listowel and he will stop to listen at each one. But the only noise is from the dogs barking in the lane between the houses and the sports field.

‘They can sense it,’ my father says. ‘Stay quiet now. Stay quiet and you will hear them.’ He sits at the end of my bed. I can only make out his shape. There is comfort in the tiny orange glow of his cigarette. ‘Listen close,’ he says again, ‘the riders will come soon.’

I am ten years old. My imagination swells in the darkness. My father lives between the story and the reality. He has spent his life faltering between the two. It is his gift and his tragedy. He can make me believe anything.

‘Now! Now! Sit up,’ he says. ‘Do you hear them? They are riding to hell!’

I hear everything that he wills into being: the hooves pounding the midnight earth, the hard music of armour, sword and spur and men’s voices shouting in the late autumn of 1600. Captain Wilmot’s cavalry – armed with the finest muskets Queen Elizabeth’s treasury can procure – stop before the gates of Listowel Castle and by the banks of the River Feale, which flows out of the mountains in neighbouring County Limerick, meandering around Listowel on its way to the Atlantic coast nearby. The garrison refuse to surrender. Above the swift water heads fly. The blood seeps into the salmon pools. Nine Englishmen are killed, but the Irish cannot hold out. They beg for terms but are refused. They must accept the captain’s discretion, which means death in a more or less dreadful form. Wilmot kills them by hanging, a comparative leniency by the bloody standards of the day, according to my father. After the surrender, the legs of eighteen suffocating men kick to the laughter of Wilmot’s men. My father reaches to his throat to mimic the act of hanging.

The priest who is found with the garrison is spared, however. Not for him the breaking of joints with heavy irons, the agonising death that is the fate of another clergymen found near Dingle. The priest has a bargain to offer. He tells Wilmot that the rebel Lord Kerry’s son, ‘but 5 years old … almost naked and besmirched with dirt’,1 (#litres_trial_promo) has been smuggled out of the castle by an old woman. Who better than the heir to lure the lord into surrender? The old woman and boy are found in a hollow cave and are sent to Dublin with the priest, but their fate is not recorded.

My father pulls ghosts out of history every night. I know that in reality there are no riders as the field behind my grandmother’s house is unmarked when I check it the next morning. ‘Sure that’s your father for the stories,’ Hannah jokes to me when I return. My grandmother has stories too. She is part of more recent wars. If only she would tell me. She fought the English and was threatened with execution. But her stories will remain untold in her own voice.

I am grown and my father is dead when I discover how faithfully he brought the Elizabethan past to life. In the late sixteenth century the conquering English had swept their enemies before them. After capturing Listowel they rode on into Limerick. The president of Munster, Sir George Carew, reported back to London that they had killed ‘all man-kind that were found therein, for a terror to those that should give relief to renegade traitors; thence we came into Arlogh Woods [in County Limerick] where we did the like, not leaving behind us man or beast or corn or cattle’.2 (#litres_trial_promo) Livestock was slain by the thousand and corn trampled and burned. The Irish peasants were butchered or driven away so that rebels and plotting Spaniards ‘might make no use of them’.3 (#litres_trial_promo) Ireland was a nest of potential traitors. The possibility of the invasion of England through the ‘back door’, to the west, loomed large in the imaginations of Tudor statesmen and soldiers. Rebellions supported by the pope and the Spanish king reinforced the English terror of the Protestant Reformation being reversed. Such endings, they knew well, only came in tides of blood. Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham had been in Paris on 24 August 1572 and lucky to escape the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Protestant Huguenots. A delighted Pope Gregory XIII offered a Te Deum and had a special medal struck rejoicing that the Catholic people had triumphed ‘over such a perfidious race’.4 (#litres_trial_promo)

The European wars of religion brought an exterminatory savagery to Ireland. In the Munster of my ancestors unknown thousands were killed in battle, slaughtered out of hand, and starved or killed by disease. The severed heads that lined the path to the tent of Sir Humphrey Gilbert – celebrated soldier–explorer and half-brother of Sir Walter Ralegh – were deemed a necessary price for making Ireland a land ripe for the benefits of English civilisation, lining the pockets of English adventurers, and keeping England safe from the existential threat posed by the kings of Catholic Europe.

II

History began with my father’s stories. It was our history. He had no interest in complex agency, only in the evidence of English perfidy of which there was abundant evidence on our long walks during holidays around the ruined castles of north Kerry. Eamonn was a professional actor, one of the most gifted of his generation, and his voice, the rich, beguiling voice of those stories, has followed me all my days. I walked beside him through the lands of the O’Connors – taken by the English Sandes family, who came with Cromwell in 1649 – to Carrigafoyle Castle with its gaping breach where the Spaniards and Italians, and their Irish allies, were massacred fleeing into the mud of the estuary – and to Teampallin Ban on the edge of Listowel where, under the thick summer grass, lay the bones of the Famine dead. That was the ‘hungry grass’ said my father. Walk on the graves and you would always be hungry.

My father the actor (Author’s Private Collection)

In those days Eamonn was a romantic nationalist. My mother Maura was a supporter of the Irish Labour Party and a committed feminist. She disdained nationalist politics. For her the struggle to achieve equal pay and control over her own body were the greater causes. A memory: being sent to Gleeson’s chemist on the corner in Terenure, five minutes’ walk from home, to ask for a package. The brown paper envelope I carried home contained ‘the pill’, something so secret I could not tell a soul. Only later did I learn how the chemist and my mother, in their quiet way, defied the law of the land which forbade women the right to decide if and when they would have children. Maura was raised in a house where no politics was spoken. Her father, Paddy Hassett, had been an IRA man in Cork but he had left the movement when the Civil War started in 1922. Most of his colleagues took up arms against the new Irish state. The only other trace of the revolutionary past I can find in my mother’s life was her friendship with our neighbour, Philippa McPhillips, niece of Kevin O’Higgins, the Free State Justice Minister assassinated by the IRA in 1927 in revenge for his part in the draconian policy of executing Republican prisoners during the Civil War. It was not a political friendship – they were good neighbours – but my mother always spoke of O’Higgins as a man who had been doing what he believed was his best for the country. He was a man we should remember, she said. Still, when my father suggested I should be named after a dead IRA man, my mother acquiesced: Eamonn Keane was a force of nature and not easily refused. Twenty-year-old Fergal O’Hanlon had been killed during a border campaign raid on an RUC barracks on New Year’s Day 1957. The raid was a disaster, and the IRA campaign faded away for lack of support. But O’Hanlon and his comrade Sean South were ritually immortalised by way of ballad:

Oh hark to the tale of young Fergal Ó hAnluain

Who died in Brookboro’ to make Ireland free

For his heart he had pledged to the cause of his country

And he took to the hills like a bold rapparee

And he feared not to walk to the walls of the barracks

A volley of death poured from window to door

Alas for young Fergal, his life blood for freedom

Oh Brookboro’ pavements profused to pour.

(Maitiú Ó’Cinnéide, 1957)

I grew up in Dublin. The city of the mid- to late 1960s was a place of rapid social change. The crammed tenements of James Joyce’s ‘Nighttown’ with its ‘rows of flimsy houses with gaping doors’,5 (#litres_trial_promo) were mostly gone, their residents dispatched to the suburban council estates and tower blocks as a new Ireland, impatient for prosperity, straining to be free of dullness and small horizons, came into being. Nationalism had a grip on us still. But it had to compete with other temptations. The city of elderly rebels and glowering bishops was also the home to the poet Seamus Heaney, the budding rock musician Phil Lynott, the young lawyer and future president Mary Robinson; the theatres and actors’ green rooms of my father’s professional life were filled with characters who seemed to live bohemian lives untroubled by the orthodoxies of church and state. The country’s most famous gay couple – though it could never be stated openly – ran the Gate Theatre next to the Garden of Remembrance where the heroes of the 1916 rebellion were commemorated. My mother intimated that Micheál McLiammóir and Hilton Edwards were ‘different’ and left it at that. To me they were simply a slightly more mysterious element in the noisy, extravagant, colourful world through which my father moved in the late 1960s. They were part of my cultural milieu, along with English football teams and imported American television series. Still, my father’s attachment to romantic nationalism defined how I saw history. Or I should say how I ‘felt’ history – because thinking played much the lesser part of all that I absorbed in those days.

Dominic Behan visited our home in Dublin. So did the Sinn Féin leader and IRA man Tomás Mac Giolla, and several other Republican luminaries, though by then the IRA was drifting far to the left. My father played the role of the martyred hero Robert Emmet in a benefit concert for Sinn Féin. By that stage the leadership of the organization had drifted to the left, towards doctrinaire Marxism and away from the militarist nationalism of earlier times, but it could still summon up the martyred dead to rally more traditional supporters. My father never hated the English as a people. In drink he would swear damnation on the ghost of Cromwell and weep over the loss of ‘the north’. But he was too imbued with the magic of the English language to be capable of cultural or racial chauvinism. Shakespeare and Laurence Sterne and John Keats had lived in his head since childhood. In one of his many flights of fancy he would even claim kinship with the great Shakespearean English actor Edmund Kean.

Irish history for my father was a series of tragic episodes culminating in the sacred bliss of martyrdom and national redemption. In 1965, the year I was sent to school, Roger Casement’s remains were finally brought home to Ireland. The British had hanged Casement as a traitor in 1916 after he attempted to bring German guns ashore to support the Easter Rising. For nearly fifty years the authorities had refused to allow Casement’s body to be exhumed from his grave in London’s Pentonville Prison, and repatriated. When in March his body was finally brought back to Dublin for burial, my father placed a portrait of Casement on our living-room mantelpiece and told me to be proud of a man who had given up all the honours England could offer in order to fight for Ireland.

On the day of his belated state funeral we were given a half day off from school. The ceremony was broadcast on national television. Our eighty-two-year-old President, Éamon de Valera, defied the advice of his doctors and went to Glasnevin cemetery to tell the nation that Casement’s name ‘would be honoured, not merely here, but by oppressed peoples everywhere’. The following year, Ireland commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising. I remember a ballad that was constantly on the radio. We sang it when we played games of the ‘Rebels and the English’ in the lanes of Terenure in the suburbs of Dublin. I can recall some of the words still:

And we’re all off to Dublin in the green, in the green

Where the helmets glisten in the sun

Where the bay’nets flash and the rifles crash

To the rattle of a Thompson gun …6 (#litres_trial_promo)

The song, by ‘Dermot O’Brien and his Clubmen’, stayed in the charts at number one for six weeks. There was also a slew of commemorative plays, concerts and films for the fiftieth anniversary. Nineteen sixty-six was a big year for my father. He played the hero William Farrell in the television drama When Do You Die, Friend?, which was set during the failed rebellion of 1798. The performance won him the country’s premier acting award. I watched a video of the production for the first time a few years ago. There is a wildness in my father’s eyes. It erupted suddenly in my present. I felt shaken as the old wildness in his nature flashed before me.

I was later sent to school at Terenure College, a private school run by the Carmelite order, where there was conspicuously little in the way of nationalism apart from some small echoes in the singing classes of Leo Maguire, a kind man we nicknamed ‘The Crow’, whose radio programme on RTE featured such staples as ‘The Bold Fenian Men’ and ‘The Wearing of the Green’, harmless stuff in those becalmed days. What I did not know was that during the Civil War the IRA blew up a Free State armoured car outside our school, badly wounding three soldiers and two civilians. None of that bloody past whispered in the trees that lined our rugby pitches.

On Easter Sunday 1966, my father took me into Dublin to watch the anniversary parade of soldiers passing Dublin’s General Post Office. De Valera was there to take the salute, although he stood too far above the heads of the crowd for me to see. Elderly men with medals formed a guard of honour below the reviewing stand. They did not look like heroes; they were just old men in raincoats and hats. Only the dead could be heroes. Like Patrick Pearse, my personal idol in those days. He was handsome and proud and gloriously doomed. My father often recited his poems and speeches.

I read them now and shiver. After nearly three decades reporting conflict I recognise in the words of Pearse a man who spoke of the glory of war only because he had not yet known war: ‘We must accustom ourselves to the thought of arms, to the use of arms. We may make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people,’ he wrote, ‘but bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing, and a nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.’7 (#litres_trial_promo)

In Ireland they were still shooting the ‘wrong’ people a hundred years after Pearse’s death. The dissident Republican gunmen who swore fealty to his dream, and the criminal gangs who killed with weapons bought from retired revolutionaries, were at it still.

The following year, at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, my father played the lead role in Dion Boucicault’s The Shaughraun, a melodrama set during the Fenian struggles of the mid-nineteenth century. Early in the play one of the characters speaks of the dispossession of her people by the English and swears vengeance: ‘When these lands were torn from Owen Roe O’Neal in the old times he laid his curse on the spoilers … the land seemed to swallow them up one by one.’8 (#litres_trial_promo) Eamonn played a roguish poacher who outwits the devilish oppressors. During the play he was shot and seemed to be dead. I had been warned that it would happen but the impact of the gunfire, the sight of him falling, apparently dead, was still traumatic. Afterwards I found him alive backstage. My first experience of the power of the gun ended in smiles and embraces.

I was sent to Scoil Bhríde, an Irish-speaking school in the city which had been founded by Louise Gavan Duffy, a suffragist and veteran of the 1916 Rising, and built on land where Patrick Pearse first established a school in 1908. Michael Collins reputedly hid there during the guerrilla war against British rule in Ireland. We children read aloud the 1916 Proclamation of the Republic and memorised the names of the fallen leaders. ‘We stood twice as tall,’ Bean Uí Cléirigh, my old teacher, told me years later. ‘We felt we could stand with any nation on earth.’9 (#litres_trial_promo) All I had to do was breathe the air of the place to feel pride in the glorious dead.

I learned that heroism in battle came from a time before the wars with the English. My father read to me the legend of Cù Chulainn, our greatest hero, who loomed out of the mythic past dripping in the gore of his enemies. Pitiless and self-distorting violence runs through the narratives:

The first warp-spasm seized Cú Chulainn, and made him into a monstrous thing, hideous and shapeless, unheard of. His shanks and his joints, every knuckle and angle and organ from head to foot, shook like a tree in the flood or a reed in the stream. His body made a furious twist inside his skin, so that his feet and shins switched to the rear and his heels and calves switched to the front … The hair of his head twisted like the tangle of a red thornbush stuck in a gap; if a royal apple tree with all its kingly fruit were shaken above him, scarce an apple would reach the ground but each would be spiked on a bristle of his hair as it stood up on his scalp with rage.10 (#litres_trial_promo)