Notice of Runic Inscriptions Discovered during Recent Excavations in the Orkneys

James Farrer

Notice of Runic Inscriptions Discovered during Recent Excavations in the Orkneys

PREFACE

As the following pages are intended only for private circulation among friends and acquaintances, and for presentation to those few Public Societies to whom such a subject may be interesting, it is hardly necessary to offer any apology for the many imperfections in the description of Maes-howe, which may doubtless be pointed out, and for the brief and cursory manner in which the subject is handled. I desire only to give a plain statement of facts, in the hope that attention may be drawn to this interesting discovery, and possibly some further impetus given to the elucidation of Runic literature. I have received from the learned professors, whose translations are given, much valuable information, of which, however, I can only partially avail myself, in consequence of my very imperfect acquaintance with Runology.

I may add, that every possible care has been taken to ensure accuracy in the drawings. These and the ground plans were made by Mr. Gibb of Aberdeen – of whose care and accuracy in the drawings of ancient monuments Mr. Stuart has spoken so strongly in his “Sculptured Stones of Scotland,” printed for the Spalding Club. The Runes were mostly drawn by my friend Mr. George Petrie of Kirkwall, and the drawings afterwards compared by Mr. Gibb with the originals in the building of Maes-Howe. Two separate sets of casts were made for me by Mr. Henry Laing of Edinburgh (one of which is now in the National Museum of the Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, and the other in the Museum of the Royal Northern Society of Antiquaries at Copenhagen.) Nothing could exceed the pains taken by Mr. Petrie and Mr. Gibb; and the drawings made by Mr. Gibb were on two occasions collated by him with the casts in Edinburgh, so that I have every reason to believe that they are as perfect representations of the original writings on the walls of Maes-Howe as can be hoped for, and not the less so that the gentlemen who made the drawings and collations were unacquainted with Runes. I have confined myself to the interpretations furnished by the three eminent northern antiquaries who have undertaken the task of deciphering these rude inscriptions, feeling assured that the high reputation which they enjoy is a sufficient guarantee for the accuracy of their translations. In concluding these few remarks I am anxious to bear testimony to the valuable assistance I have received from my friend Mr. John Stuart, Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, to whom in reality I am chiefly indebted for the discovery of Maes-Howe, since I owe to his urgent suggestion that the great circle of Stennes, and the tumuli around it, had not been sufficiently examined, the successful excavation of this ancient “howe.” It is also highly satisfactory to me to know that Mr. Balfour of Balfour and Trenabie, on whose property this interesting relic of antiquity is situated, has taken the necessary steps to ensure its preservation – a precaution, unfortunately, too often neglected under similar circumstances.

JAMES FARRER.Ingleborough, Yorkshire, June 1862.

MAES-HOWE

Early in the month of July 1861 I was enabled, by the kind permission of my friend David Balfour, Esq. of Balfour and Trenaby, to put in execution a scheme long contemplated, but from various circumstances unavoidably delayed, the excavation of some of the great tumuli in the neighbourhood of the Stones of Stennes, or Ring of Brogar. I had in the year 1854 partially explored one of considerable size on the east side of the great circle of stones, which stands on the west shore of the Loch of Harray. No discovery, however, of any importance was then made.

Some days were devoted to excavations close to Stennes, to which allusion will afterwards be made, but as several gentlemen of well-known antiquarian reputation from Edinburgh and Aberdeen were expected, and as I was desirous of having the benefit of their experience and advice, I determined at once to commence operations on the great tumulus of Maes-howe, the subject of this notice. My attention had been particularly called to this tumulus by Mr. Balfour, whose decided opinion that a careful examination might result in some important discovery, afforded me great encouragement, as I well knew that he had for many years taken considerable interest in Orkney antiquities, and his opinion that Maes-howe was a sepulchral chamber, appeared to be confirmed by local traditions.1

On the afternoon of Saturday the 6th of July, therefore, guided by the experience of Mr. George Petrie, and assisted by the professional knowledge of Mr. Wilson, road contractor, ground was broken on the west side of Maes-howe, and on the same evening, Mr. John Stuart and Mr. Joseph Robertson of Edinburgh, with Colonel Forbes Leslie of Rothie, and Mr. James Hay Chalmers of Aberdeen, arrived by the Prince Consort steamship. As it was anticipated that a couple of days would suffice to make a large opening in the tumulus, arrangements were made for meeting there on the 10th of July. Before proceeding with the description of what followed, it may not be out of place to give a short account of the Stones of Stennes, as described by Lieutenant Thomas in a work published by him in 1851: —

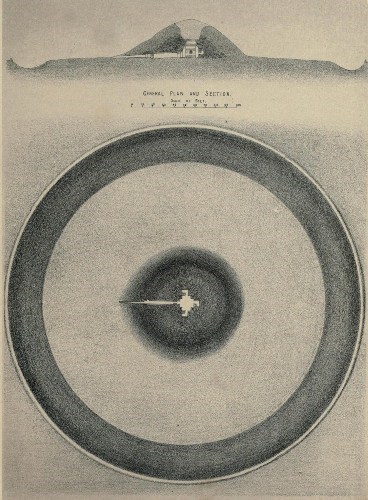

“The Great Circle of Stennes, or Ring of Brogar, is a deeply entrenched circular space containing almost two acres and a half of superficies, of which the diameter is 366 feet. Around the circumference of the area, but about thirteen feet within the trench, are the erect stones, standing at an average distance of eighteen feet apart. They are totally unhewn, and vary considerably in form and size. The highest stone was found to be 13-9 feet above the surface, and judging from some others which have fallen, it is sunk about eighteen inches in the ground. The smallest stone is less than six feet, but the average height is from eight to ten. The breadth varies from 2-6 to 7-9 feet, but the average may be stated at about 5 feet, and the thickness about 1 foot – all of the old red sandstone formation. The trench round the area is in good preservation. The edge of the bank is still sharply defined, as well as the two foot-banks or entrances, which are placed exactly opposite to each other. They have no relation to the true or magnetic meridian, but are parallel to the general direction of the neck of land on which the circle is placed. The trench is 29 feet in breadth, and about 6 in depth, and the entrances are formed by narrow earth-banks across the fosse. The surface of the enclosed area has an average inclination to the eastward. It is highest on the north-west quarter, and the extreme difference of level is estimated to be from 6 to 7 feet. The trench has the same inclination, and therefore could never be designed to hold water.”

The Excavation of Maes-Howe

On Monday the 8th of July, a number of men under the superintendance of Alexander Johnson, Mr. Wilson’s foreman – a most active and intelligent fellow – proceeded with the work that had been commenced on the previous Saturday, and before evening discovered a passage on the west side, which afterwards proved to be the entrance into the interior of the tumulus. This passage was covered over with large flag-stones, one of which having been with some difficulty upraised, we effected an entrance, but found a considerable accumulation of earth and stones, which was removed on the following day, and Mr. Wilson, after careful examination, in which his engineering experience was of the highest importance, agreed to my suggestion that the excavation should be proceeded with from the centre of the hillock.

I am chiefly indebted to my friend Mr. George Petrie for the following measurements, which I believe will be found to be substantially correct: —

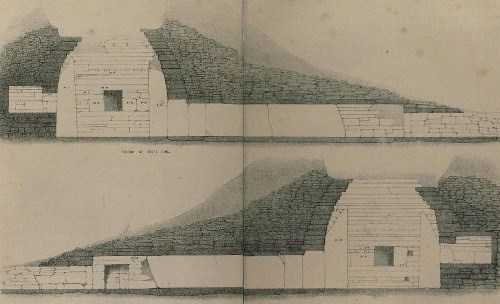

The tumulus is about 92 feet in diameter, 36 feet high, and about 300 feet in circumference at the base. It is surrounded by a trench 40 feet wide, and varying in depth from 4 to 8 feet. It is situated on the north side of the new road leading to Stromness from Kirkwall, being about 6 miles from the former, and 9 from the latter place. It is about 200 yards distant from the road, and a mile and a half from the Stones of Stennes. It has undoubtedly been entered at some remote period, probably by the Northmen, who, as is well known, were not deterred by feelings either of religion or superstition, from opening and ransacking any place likely to repay them for their trouble. Whether they were the first to break into the building, or whether they found it in a state of comparative ruin, the natural result of great antiquity, can now only be matter of conjecture. It is obvious that little respect has been paid to the dead, since the stones used for closing up the cells, in which it is supposed they were deposited, were found torn out and buried in the mass of ruins filling up the interior of the chamber to which these cells are attached.

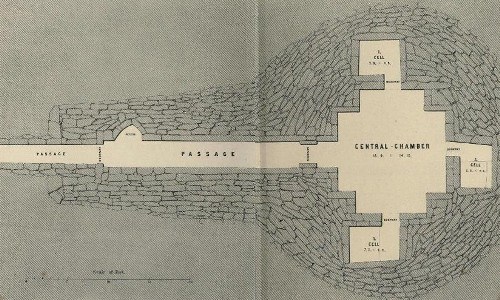

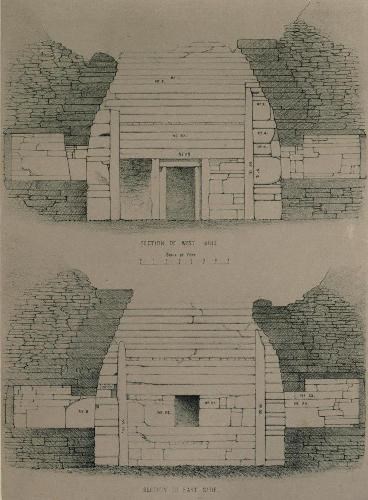

The passage leading to the central chamber is 2 feet 4 inches wide at its mouth, and appears to have been the same in height, but the covering stones had been removed, or had fallen in for about 22½ feet. The passage then increases in dimensions to 3¼ feet in width, and 4 feet 4 inches in height, and continues for 26 feet, when it is again narrowed by two upright stone slabs to 2 feet 5 inches. These slabs are each 2 feet 4 inches broad, and immediately beyond them the passage extends 2 feet 10 inches, and then opens into the central chamber. Its dimensions from the slabs to its opening into the chamber are 3 feet 4 inches wide, and 4 feet 8 inches high. At the commencement of the passage there is a triangular recess in the wall about 2 feet deep, and 3½ in height and width, in front and opposite to it in the passage, a stone of corresponding shape and dimensions, suggesting the idea that it might have been used to close the passage, and that it was pushed back into the recess in the wall when admission into the chamber was desired. From this recess to the chamber, the sides of the passage, the floor and roof, are formed by four immense slabs of flagstone; three of these stones are broken, and the fourth slightly cracked.

After a few days’ labour the whole of the rubbish filling the chamber was removed, but long ere this was accomplished, the keen eye of Mr. Joseph Robertson discovered the first of the Runic inscriptions. They were high up on the walls of the building, smaller and less distinctly drawn than many that were afterwards discovered, but the important fact of the existence of Runic inscriptions in Orkney, where none had hitherto been found, was at once established.

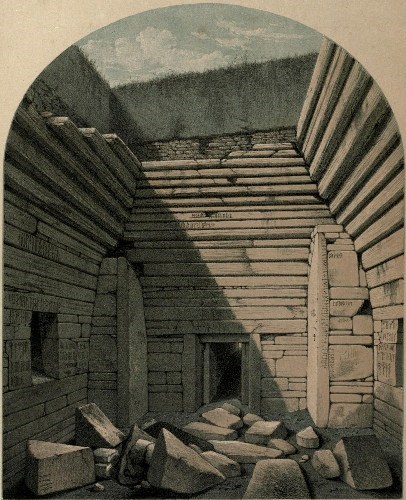

Plate II. INTERIOR VIEW OF MAESHOWE.

The chamber when cleared out proved to be about 15 feet square on the level of the floor, and 13 feet in height, to the top of the present walls. Immediately opposite to the passage is an opening in the wall 3 feet from the floor. This is the entrance to a cell or small chamber in the wall, 5 feet 8 inches long, 4½ feet wide, and 3½ high. A large flagstone is laid as a raised floor between the entrance and the inner end of the chamber. The entrance is 2 feet wide, 2½ high, and 22½ inches long. On the two opposite walls of the chamber are similar openings in the walls. The one on the right is 2½ feet wide, 2 feet 9 inches high, and 1 foot 8 inches long. It gives admission to a cell 6 feet 10 inches long, 4 feet 7 inches wide, 3½ feet high, and has a raised flagstone floor, as in the other chamber. The opening on the left is 2¼ feet wide, 2½ high, and 1¾ long, and about 3 feet above the floor of the chamber. The cell of which this is the entrance is 5 feet 7 inches long, 4 feet 8 inches wide, and 3 feet 4 inches high. It has no raised floor like the two other cells. The roofs, floors, and back walls of the cells are each formed by a single slab of stone, and stones corresponding in size and shape to the openings in the walls were found on the floor in front of them. The natural inference is that they were originally the seals of the chambers in which the honoured dead reposed.

The four walls of the central chamber converge towards the top by the successive projection of each stone or flag, commencing about 6 feet from the level of the floor, as is usually found to be the style of building, both in the Pict’s houses or burghs, and in the still more primitive subterranean dwellings known as Weems. The top of the chamber would thus necessarily be of small dimensions, and the aperture easily closed by one large flagstone. This top, or cover stone, together with a considerable portion of the upper part of the walls, has been thrown down, and the highest part of the existing walls is only about 13 feet from the level of the floor. At that point, the opposite walls have approached to within 10 feet of each other, so that the chamber is now 15 feet square at the floor, and 10 feet at the top of the walls, in their present condition.

Large quantities of earth had been piled up over the building when completed. In each angle of the central chamber stands a large buttress, doubtless intended to strengthen the walls, and support them under the pressure of their own weight, and that of the mass of earth with which the whole was covered. These buttresses vary somewhat in dimensions, but they are on an average about 3 feet square at the base, and from 9 to 10 feet high, with the exception of one which is only 8 feet high. In each buttress one side is formed by a single slab. The walls of the chamber are built with large stones, which generally extend the whole length of the wall. No lime or mortar of any kind has been used.

The entire number of Runic characters may be about 935, exclusive of scribbles and many doubtful marks. The monograms and bind-runes, or connected consonants, are considered as forming one letter. There are also some marks which may have been intended to represent a horse and an otter with a fish in its mouth; also, a winged dragon and a worm knot, which last has much the appearance of one of the great Saurians. The two hind legs are very plainly defined.

Barrows at Bookan

This barrow is in the parish of Sandwick, but so near to Stennes that it may have been regarded as connected with the great circle. It is on the property of Mr. Watt of Skail, in the West Mainland. It was opened on the 6th of July, and proved to be a collection of kists or graves. At the north end of the central kist, a flint lance head, and several fragments of clay vessels or urns, were found, together with a lump of heavy metal, supposed to be Manganese, but no bones. In some of the other kists were human remains in a very decayed state, two jaw bones being the most perfect. These were much distorted.

Mr. Petrie gives me the following measurements: – The Barrow is about 44 feet in diameter, and about 6 feet high. About 11 feet within the outer margin of the base of the barrow is a circular wall or facing about 1 foot high. From the south side of this wall a low passage, 6 feet 3 inches long, 21 inches in height, and the same in width, leads to a chamber or kist 7 feet long and 4½ wide. At the north end of this there was another kist 4 feet 8 inches long, and 3 feet wide. On the east side there was one 4 feet 8 inches long, and 2 feet 9 inches wide; and on the west side two kists, both of which were of the same length as that on the east side, and both were 3 feet in width. They were all about 2 feet 8 inches deep. The foundation of the surrounding wall or facing was considerably above the level of the floors of the kists.

LARGE BARROW CONTAINING GRAVESThe excavation of this barrow was commenced on the 17th of July 1854. It was found to contain graves, in one of which was an urn with a quantity of burnt bones and ashes. It was formed out of a micaceous stone not belonging to Orkney. It was 1 foot 9 inches in diameter, about 18 inches deep, and 5 feet 10 inches in circumference, the rim, which projected on the outside all round, was an inch and a half wide, the kist in which it was deposited was 2 feet and a half in length, and 2 feet in width, but the side stones which protected the kist were nearly 6 feet in length, and at the angles, and on the outside of the kist were quantities of small rolled pebbles and gravel, probably intended to assist in draining off water. Clay was placed inside the kist at the different angles; the flags were about an inch and a half thick, but much decayed; the cover stone was of an irregular shape, about 4 feet long and 2½ wide; the urn rested upon the corners of four flags; it was partly decayed, and could not be removed till after an interval of two days, when I succeeded in raising it. It is now in the Museum of the Society of Antiquaries at Edinburgh, to whom I presented it, with the consent of Mr. Balfour.

In another grave within the same barrow was found a small urn composed of baked clay and gravel, nearly filled with soil, and only one or two small pieces of bone. It was brought to Kirkwall, but could not be preserved, in consequence of its decayed condition. It was 5 inches in diameter, 17 in circumference, and 5 deep. The kist was 2 feet 9½ inches long, and 1 foot 7 inches wide. The bones, in this instance, had not been placed in the urn, but were laid on a flagstone in the north-west angle of the kist. It is not improbable that further investigation might lead to the discovery of other interments within the same barrow, since neither of those before described were in the centre of the tumulus, and several instances have occurred where they have been found near the outside.

Mounds at Stennes

In the year 1854, I had partially opened one of the largest of these hillocks, but further examination last July did not encourage the belief that it was sepulchral. I was however advised to examine one on the west side of the Stones of Stennes, and directly opposite to the one previously mentioned. In both of them the workmen penetrated to a depth of 22 feet, and over an area of 9 square feet in the one on the west side of the great circle, but there was no appearance of any kind of building. The material of which these hillocks are composed is precisely the same as that which still exists within the circle of stones, and I infer that when the moat surrounding the circle was excavated, advantage was taken of the circumstance to raise these hillocks. Fragments of animal, but no human bones, were found in each, but in both instances near the top. Building stones are found at the base of both hillocks, but always embedded in the soil; those which were easy of removal having no doubt been long since taken away by the country people. Sections were made at right angles in both of the hillocks, and it was clearly ascertained that no building of any size could be concealed within.

Tenstone

In this barrow, which is in the parish of Sandwick, but adjoining Stennes, I found the remains of two stone urns. The barrow had been evidently previously opened. There was reason to believe that these urns had been in separate kists. They were formed out of a micaceous stone, but the attempt to unite the fragments was quite hopeless. A few small pieces of human bone were found. The cover and sidestones of the kists remained in the grave.

Plate III.

Plate IV. GROUND PLAN OF CENTRE CHAMBER &c.

Plate V.

Plate VI.

APPENDIX

Origin of Maes-Howe.

It is proposed now to inquire into the origin of Maes-Howe, at what time, and for what purpose it was constructed, and who were the people whose names and writings are found engraved on its walls. I am indebted to the learned Professors who have furnished me with their translation of the inscriptions, for the information which is embodied in the following pages.

It is much to be regretted that the inscriptions are so indefinite, and frequently so much defaced. Moreover, Nos. 19 and 20 alone make any allusion to the erection of Maes-Howe. Professor Rafn believes that it was a sorcery hall for Lodbrok,2 a female magician, Professor Munch, that it was the burial-place of a woman of the same name, while Professor Stephens, who expresses no opinion as to the time when the building was raised, considers the writings which speak of Lodbrok’s sons, as indicative of its having been used in early times by the celebrated Scandinavian Vikings of that name, as a fortress and place of retreat. The low and narrow cells, as well as the low passage leading to the interior, fully justify the opinion that it was undoubtedly at one time a place of burial. The massive stones forming the floor and side walls of the passage, and also those used in the inside to support the buttresses, are similar in character to the neighbouring circle of stones at Stennes. The architecture also is most primitive, and it is evident that the whole work must have been one requiring much time and labour. The present form of the mound does not favour the idea that it was originally a platform, and used for the performance of religious rites, though this would not be inconsistent with the idea that it had been adopted to that purpose at some remote period, having been previously used as a place of interment.

If we find difficulty in determining the period when the mound was first raised, almost equal difficulty arises in assigning to any fixed time the engraving of the numerous inscriptions. Many of them are no doubt to be attributed to the Crusaders, but there are others of probably far earlier date than the twelfth century, when, as stated by Professor Munch, the Orkney Jarl, Ragnvald, about the year 1152-3, organized his naval expedition to the Holy Land. That the writings have been engraved at intervals during a long period of time – perhaps, as suggested by Professor Stephens, during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries, or even later – is sufficiently obvious. Some of the stones have the words very faintly and imperfectly engraved, while in others the lines are sharply and distinctly cut. The absence of division between the letters (for the dots are very uncertain in their position, and are probably for the most part accidental) sufficiently accounts for the difference of reading, in several of the inscriptions. The variety of type – there being no fewer than 18 different forms of A, many of them it is true, like, but still different; to say nothing of Diphthongs, the Bind-runes, or consonants and vowels connected, as