По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

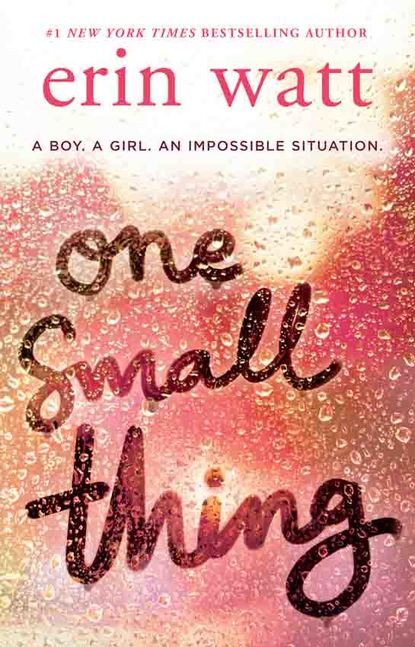

One Small Thing: the gripping new page-turner essential for summer reading 2018!

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“What about this?”

I follow the line of her finger to the messenger bag hanging on the hook in the section next to mine. “What about it?”

“Your bag is in Rachel’s section,” she says. “You know how she didn’t like that.”

“So?”

“So? Take it off of there.”

“Why?”

“Why?” Her face grows tight and her eyes bulge. “Why? You know why. Take it off now!”

“I—You know what, fine.” I reach past her in a huff and drop the bag in my section. “There. Are you happy?”

Mom’s lips press together. She’s holding back some scathing comment, but I can read the anger in her eyes clear enough.

“You should know better” is what she says before spinning on her heel. “And clean off that dog hair. We don’t allow pets in this house.”

The furious retorts build in my mouth, clog up my throat, fill up my head. I have to clench my teeth so hard that I can feel it in my entire jaw. If I don’t, the words will come out. The bad ones. The ones that make me look uncaring, selfish and jealous.

And maybe I am all those things. Maybe I am. But I’m the one still alive and shouldn’t that matter for something?

God, I can’t wait until I graduate. I can’t wait until I leave this house. I can’t wait until I’m free of this stupid, awful fucking prison.

I tear at my shirt. A button pops off and pings onto the tile floor. I curse silently. I’ll have to beg Mom to sew this on tonight because I have only one work shirt. But screw it. Who cares? Who cares if I have a clean shirt? The customers at the Ice Cream Shoppe will just have to avert their eyes if a few strands of dog hair and chocolate sauce are sooooo offensive.

I shove the dirty shirt into the mudroom sink and strip off my pants for good measure. I saunter into the kitchen in my undies.

Mom makes a disgusted sound at the back of her throat.

As I’m about to climb the stairs, a stack of white envelopes on the counter catches my eye. The writing is familiar.

“What are those?” I ask uneasily.

“Your college applications,” she replies, her voice devoid of emotion.

Horror spirals through me. My stomach turns to knots as I stare at the envelopes, at the handwriting, the sender addresses. What are they doing there? I rush over and start rifling through them. USC, University of Miami, San Diego State, Bethune-Cookman University.

The dam of emotions I was barely holding in check before bursts.

I slap a hand over the pile of envelopes. “Why do you have these?” I demand. “I put them in the mailbox.”

“And I took them out,” Mom says, her eyes still focused on the carrots in front of her.

“Why? Why would you do that?” I can feel myself tearing up, which always happens when I’m angry or upset.

“Why would you apply? You’re not going to any of them.” She reaches for an onion.

I place my hand on her wrist. “What do you mean I’m not going to any of these colleges?”

She plucks my hand off and meets my glare with a haughty, cold stare of her own. “We’re paying for you to go to school, which means you’ll go where we tell you—Darling College. And you don’t need to keep asking for applications. We’ve already filled yours out for Darling. You should be accepted in October or so.”

Darling is one of those internet colleges where you pay for your degree. It’s not a real school. No one takes a degree from Darling seriously. When they told me over the summer that they wanted me to go there, I thought it was a joke.

My mouth drops. “Darling? That’s not even a real college. That’s—”

She waves the knife in the air. “End of discussion, Elizabeth.”

“But—”

“End of discussion, Elizabeth,” she repeats. “We’re doing this for your own good.”

I gape at her. “Keeping me here for college is for my own good? Darling’s degrees aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on!”

“You don’t need a degree,” Mom says. “You’ll work at your father’s hardware store, and when he retires you’ll take that over.”

Chills run down my spine. Oh my God. They’re going to keep me here forever. They’re never, ever going to let me go.

My dream of freedom has been snuffed like a hand over a candle flame.

The words tumble out. I don’t mean for them to come out, but the seal breaks.

“She’s dead, Mom. She’s been dead for three years. My bag hanging from her hook isn’t stopping her from coming home. Me getting a dog won’t stop her from rising from her grave. She’s dead. She’s dead!” I scream.

Whack.

I don’t see her hand coming. It strikes me across the cheek. The band of her wedding ring catches on my lip. I’m so surprised that I shut up, which is what she wanted, of course.

Her eyes widen. We stare at each other, chests heaving.

I break first, tearing out of the kitchen. Rachel might be dead, but her spirit is more alive in this house than I am.

2 (#u407069dc-801a-58d4-a7c7-745d946eaa95)

“I don’t want to go.” Scarlett’s firm tone doesn’t waver. We’ve been standing in front of the gas station for twenty minutes arguing about our plans, and my best friend isn’t budging.

Neither am I. My cheek still throbs from Mom’s earlier strike.

The girls who invited us to the party lean against the side of a black Jeep with its top down, their heavily made-up faces wrinkled with annoyance. The dark-haired guy in the driver’s seat looks impatient. I’m surprised they’re waiting around. I mean, it’s not like they know us. Their invitation was the result of a five-second conversation in the potato chip aisle after I told the blonde that I liked her shirt.

“Fine. Then don’t go,” I say to Scarlett.

Her brown eyes flood with relief. “Oh, okay, good. So we’re not going?”

“No, you’re not going.” I lift my chin. “I am.”

“Lizzie—”