По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

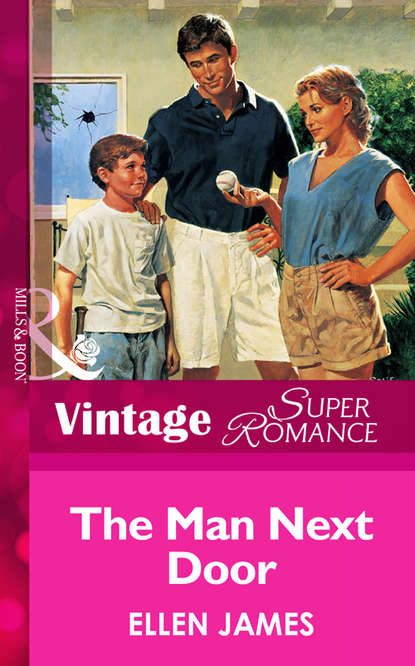

The Man Next Door

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The boy watched her closely, as if he still expected a lecture and couldn’t leave until it was over with.

“We only moved in two days ago,” he said, perhaps hoping that would exonerate him.

Kim glanced across at the house next door. She knew she’d retreated inside herself these past few months…ever since Stan’s death. She’d been only vaguely aware of new neighbors moving in. “I haven’t met your mother yet,” she said reluctantly.

The boy poked his toe at the ground. “My mom’s not here. She’s in England. I have to stay with my dad. But just for the summer.”

From behind Kim, another voice spoke—a man’s voice, deep and unfamiliar.

“Don’t make it sound like a prison sentence, Andy.”

The boy turned. “Dad,” he mumbled with a marked lack of enthusiasm.

Kim turned, too, and studied the child’s father. The family similarities were striking; this was the man the boy would become. He was tall, lean in a way that hinted at strong muscles. He had dark rumpled hair and brown eyes the color of toffee. But they weren’t soft eyes; there was a hardness to them, something that put Kim on guard.

“Michael Turner,” he said. “Your new neighbor. I believe you’ve already met my son.” He gave only the briefest of smiles, just enough to hint at a few attractive crinkles around his eyes. Laughter lines, perhaps? Except that he didn’t look like the kind of person who laughed readily.

Kim realized she was staring. But she didn’t smile back at him. These past few months, she’d lost the knack of smiling.

“Yes. Andy and I have met,” she said.

The boy’s gaze traveled guiltily toward the broken window. Michael Turner stepped over to inspect the damage.

“Guess you’d better explain, son,” he said calmly.

Andy’s young face grew belligerent. “You can see what happened,” he muttered. “What’s to explain?”

Michael Turner drew his brows together and regarded Andy. His face was as expressive as his son’s—Kim caught a glimpse of exasperation and puzzlement in his dark intent eyes. But she saw something else there. She saw the love. In that instant, she sensed that this was a man who cared very much for his son. In the same instant, she realized that Michael and Andy Turner didn’t know how to talk as father and son. They stood warily apart, as if unsure how to take the first step toward each other.

Kim gripped her shovel. Why did she feel such protectiveness toward a child she’d only just met? And why did she want to tell Michael Turner that he ought to exercise his laughter lines a little more?

Kim pushed the shovel into the ground, wishing she could get back to work and forget about the two Turner males who had intruded on her life. But they would not be ignored. They remained in her yard beside the broken window.

“Andy,” Michael Turner said, “you have an apology to make.”

Andy stuffed his hands deeper into his pockets. Again he managed to look both stubborn and unsure at the same time. He didn’t say anything, glancing covertly at his father now and then. Michael Turner gazed back steadily at his son. In the end, the man won out over the boy. Andy grudgingly addressed Kim.

“I’m sorry,” he mumbled.

Kim leaned on her shovel and considered the situation. After a moment she shook her head.

“Apology not accepted,” she pronounced.

Both Turners stared at her. For this moment at least, they seemed united in their surprise at Kim’s words. Then Michael Turner frowned.

“Son,” he said, “I think you’d better run along home.”

Andy hovered for a second or two. Kim suspected it had become a habit with him not to obey his father right away—perhaps as a point of honor. But at last he began sidling across the yard. He seemed about to go sprinting off when he gave Kim a glance. She felt it more than ever—a quick unreasoning affinity with this boy. And, from the brightness in his eyes, she knew he felt it, too. Then he turned and finally did go sprinting off, his too—big sneakers thumping over the grass. He reached the house next door and promptly disappeared around the side.

Kim took a deep breath. What was wrong with her? The boy had a mother, whether or not she happened to be in England. Kim was just the neighbor lady. If she had any misguided maternal instincts, she ought to forget about them.

She gripped her shovel again, but it seemed she still had Michael Turner to deal with.

“So it wasn’t the best apology in the world,” he remarked. “But it was an apology.”

“Not good enough,” Kim said.

“I’ll repair the window.”

“Well, that’s the point,” she said. “Don’t you think Andy should be the one who does the repairing?”

Michael Turner looked thoughtful. “Are you telling me I’m too lenient with my son?”

Kim shrugged. “I wouldn’t know. I’ve barely set eyes on the two of you. I’m just telling you what my terms are.”

He examined her with disconcerting thoroughness. “So we’re negotiating,” he said.

“Something like that.” Kim paused. She didn’t like the way her gaze kept returning to this man, drawn by some enigmatic quality in him. He gave a disquieting impression of restrained power. “Andy mentioned that your. uh, wife is out of the country. Maybe he’s acting up because of that, who knows, but—”

“Ex—wife,” Michael Turner said impassively. “And yes, Andy isn’t too happy about being left with me for the summer. I think he made that pretty clear.”

Kim wondered irritably why she was poking into Michael Turner’s personal life. Against her will, she found herself studying him more carefully. She supposed you could call him handsome, what with his strong features, his dark eyes under dark brows. You could certainly call him virile. But surely that was another knack that Kim had lost somewhere along the way—the ability to appreciate a good—looking man. She didn’t think she’d be getting that one back anytime soon. All she felt right now was the dull, heavy emptiness that had become too familiar.

Kim glanced away from him. She focused on the bush she’d been trying to unearth when that ball had come flying into her yard. Digging her shovel into the ground, she stood on top of it, centering her weight. Just a little more, and maybe she’d finally get somewhere.

“You’re doing that all wrong,” Michael Turner said. “The way you’re tussling with that thing, you’re liable to hurt yourself.”

Kim wiped away a trickle of sweat with her gardening glove. “I can manage.”

“Perhaps. But the bush can’t.”

She glanced at him sharply, unable to detect any humor in his expression. “I don’t usually attack shrubs, if that’s what you’re thinking. But this is a special case.” She regarded the bush once more. It was an evergreen, limbs shorn naked except for three round tufts of greenery on top. The thing had always made Kim think of a spindly cheerleader waving pom—poms in the air.

Michael Turner studied the bush, too. “Sure is ugly.”

“Well, you understand then. It has to go.”

“Understand?” he said, with a tinge of impatience. “I understand that whoever trimmed it had a lousy eye and even worse execution.”

“My husband trimmed it,” she said in a stern tone that surprised even her. “Yet another reason why the damn thing’s got to go.”

Michael Turner continued to study the bush in a brooding manner. “It’s ugly all right, but what the hell. I’ll take it off your hands.”

“You can’t possibly want it,” she protested.

A flicker of dissatisfaction showed in his face, as if he’d had enough of both Kim and the bush yet a sense of duty impelled him to stay—perhaps because his son had broken her window.

“You’re right,” he said gruffly. “I don’t want.it. But I’ll take it, anyway.”