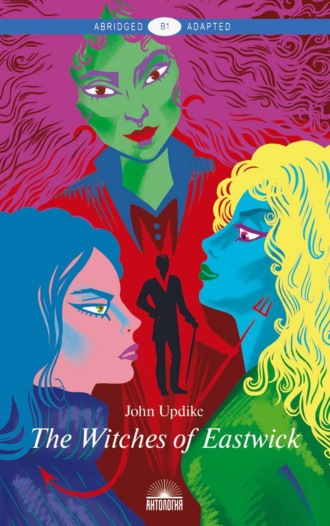

The Witches of Eastwick / Иствикские ведьмы

He stopped the car at the front door. Two steps led up to a paved, pillared porch. He opened the massive door, freshly painted black, and ushered her in. Inside the foyer, a sulfurous chemical smell greeted her; Van Horne didn't notice it, it was his element. He was not wearing baggy tweed today but a dark three-piece suit as if he had been somewhere on business. He showed her round the house, talking nonstop and widely gesturing right and left with his arms. He explained that the former ballroom would serve as his laboratories; there was nothing in that room as the equipment was still in crates. The room on the other side he called the study; he found it pretty, but again said that half his books would be in cartons in the basement till he got an air-control unit installed. In the dining room with a mahogany table he informed Alexandra that he preferred dinners on the intimate side, four, six people, where everybody had a chance to shine, instead of inviting a mob when mob psychology took over, a few leaders and a lot of sheep. He also boasted that he had some super vintage candelabra of the eighteenth-century, still packed; he wasn't going to get it up in full view until he had a burglar alarm installed.

Alexandra responded by polite noises and held herself a distance behind him in fear of being accidentally struck as the big man wheeled and gestured. And she noticed that in spite of all his talk of glories still to be unpacked, the rooms were badly underfurnished; Van Horne had the strong instincts of a creator but with only, it seemed, half the needed raw materials. Alexandra found this touching and saw in him something of herself, her monumental statues that could be held in the hand.

“Now,” he announced, booming as if to drown out these thoughts in her head, “here's the room I wanted you to see. ” It was a long living room, with an extraordinary fireplace pillared like the facade of a temple with a great mirror above the mantel, in which the lordly space of the room reflected. She looked at her own image and took off the bandanna, shaking down her hair, not fixed in a braid today. She looked younger in this antique, forgiving mirror. She looked up into it, pleased that the flesh beneath her chin did not show. In the bathroom mirror at home she looked terrible, and in the rear-view mirror in the Subaru, she looked worse yet, corpse-like in color, the eyes quite wild. As a little girl Alexandra had imagined that behind every mirror a different person waited to look back out, a different soul. Like so much of what we fear as a child, it turned out to be in a certain sense true.

Van Horne had put around the fireplace some modern armchairs and a four-cushioned sofa, brought from a New York apartment. But the room was mostly furnished with works of art, including several that took up floor space: a giant hamburger, made of violently colored vinyl, a white plaster woman at a real ironing board, with a stuffed cat rubbing at her ankles; a neon rainbow, unplugged and needing a dusting.

The man slapped an especially ugly part of the collection, a naked woman on her back with legs spread; she had been made up of chicken wire, flattened beer cans, an old porcelain chamber pot for her belly, pieces of chrome car bumper, items of underwear stiffened with lacquer and glue. Her face, staring straight up at the ceiling, was that of a plaster doll, with china-blue eyes and cherubic pink cheeks, cut off and fixed to a block of wood that had been crayoned to represent hair. “Here's the genius of the bunch for my money,” Van Horne said, wiping the corners of his mouth with a two-finger pinching motion. “That's the kind of thing you should be setting your sights toward. The richness, you know, the ambiguity. No offense, friend Lexa, but you're a Johnny-one-note with those little poppets of yours.”

“They're not poppets, and this statue is rude, a jest against women. My little figurines aren't jokes, they're meant affectionately,” she said. Yet her hand touched the big doll and found there the glossy yet resistant texture of life. On the walls of this long room, where perhaps Lenox family portraits used to hang, there now hung or protruded tasteless parodies of the ordinary – giant pay telephones in soft canvas, American flags duplicated in impasto, oversize dollar bills rendered with deadpan fidelity, plaster eyeglasses with not eyes but parted lips behind the lenses, our movie stars and bottle caps, our candies and newspapers and traffic signs. All that we wish to use and throw away with hardly a glance was here bloated and bright: permanized garbage. Van Horne led Alexandra through his collection, down one wall and back the other; and in truth she saw that he had acquired of this mocking art specimens of good quality. He had money and needed a woman to help him spend it. Across his dark vest curved the gold chain of an antique watch; he was an inheritor, though ill at ease with his inheritance. A wife could put him at ease.

The tea with rum came, but formed a more sedate ceremony than she had imagined from Sukie's description. Fidel materialized with that ideal silence of servants. The long-haired cat called Thumbkin, with the deformed paws mentioned in the Word, jumped onto Alexandra's lap just as she lifted her cup to her lips. She felt at peace here, which she had not expected, here in these rooms almost empty except their overload of sardonic art. Her host seemed pleasanter too. The manner of a man who wants to sleep with you is aggressive, testing, predicting his eventual anger if he succeeds, and there seemed little of that in Van Horne's manner today. He looked tired. She fantasized that the business appointment for which he had put on his solemn three-piece suit had been a disappointment, perhaps a petition for a bank loan that had been refused. He poured extra rum into his tea from the bottle of Mount Gay his butler had put at his elbow. “How did you come to acquire such a large and wonderful collection?” Alexandra asked him.

“My investment adviser” was his disappointing answer. “Smartest thing financially you can ever do except finding oil in your back yard is to buy a name artist before he has the name. And anyway, I love the junk.”

“I see you do,” Alexandra said, trying to help him. How could she ever rouse this heavy rambling man to fall in love with her? He was like a house with too many rooms, and the rooms with too many doors.

“I hated,” he volunteered, “that abstract stuff they were trying to sell us in the Fifties; Christ, it all reminded me of Eisenhower,[3] a big blah. I want art to show me something, to tell me where I'm, even if it's Hell, right?”

“I guess so. I'm really very dilettantish,” Alexandra said, less comfortable now that he did seem to be rousing. What underwear had she put on? When had she last had a bath?

“So when this stuff came along, I thought, Jesus, this is the thing for me. So fucking cheerful, you know – going down but going down with a smile.” He continued talking of the impression those things made on him when he had visited the modern art galleries.

He had felt that Alexandra did not mind his talking dirty. She in fact rather liked it; it had a secret sweetness, like the scent of carrion on Coal's coat. She must go. Her dog's big heart would break in that little locked car.

Van Horne told her about another creation of modern art that had impressed him greatly during his visit to Los Angeles: the entire sawed-off Dodge car sitting on a mat of artificial turf with a couple inside having an intercourse, and a little other mat of turf about the size of a checkerboard, with a single empty beer bottle on it, which showed that they had been drinking and threw it out. He called it a work of genius, and predicted that such works would be Mona Lisas of the future.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

Gilded Age – ironically for 1870–1898 in the USA

2

Gotham – nickname for New York

3

Eisenhower – the 34th President of the USA (1953–1961) Dwight David Eisenhower

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: