An Account of the Abipones, an Equestrian People of Paraguay, (2 of 3)

The gentle reader will pardon this digression concerning captives, if indeed it be a digression, because it does much towards establishing a good opinion of the chastity and benevolence of the Abipones, which form the subject of the present chapter, and will be further confirmed by additional arguments. They hospitably entertain Spaniards of the lower order, Negroes or Christian Indians, who have run away from their masters, lost their way, or, by some other means, chanced to enter the hordes of the Abipones, and, in the most friendly manner, offer them food or any thing else they may stand in need of; this they do the more cordially the more liberally these strangers abuse the Spanish nation; but if they neglect this they are taken for spies, and undergo considerable danger. They diligently watched over the safety of us Jesuits, to whom was committed the management of the colonies. If they were aware of any danger impending over us from foreign foes, they acquainted us with it immediately, and were all intent upon warding it from us. In JOURNEYS, when rivers were to be crossed, the horses got ready, sudden and secret attacks of the enemy to be avoided or repelled, it is incredible how anxiously they offered us their assistance. See! what mild, benevolent souls these savages possess! Though they used to rob and murder the Spaniards whilst they thought them their enemies, yet they never take anything from their own countrymen. Hence, as long as they are sober, and in possession of their senses, homicide and theft are almost unheard of amongst them. They are often and long absent from their homes, during which time they leave their little property without a guard, or even a door, exposed to the eyes and hands of all, with no apprehension of the loss of it, and on their return from a long journey, find every thing untouched. The doors, locks, bars, chests, and guards with which Europeans defend their possessions from thieves, are things unknown to the Abipones, and quite unnecessary to them. Boys and girls not unfrequently pilfered melons grown in our gardens, and chickens reared in our houses, but in them the theft was excusable; for they falsely imagined that these things were free to all, or might be taken not much against the will of the owner. Though I have enlarged on the native virtues of the Abipones more than it was my intention to do, I shall think nothing has been said till I have made a few observations relative to their endurance of labour. Who can describe the constant fatigues of war and hunting which they undergo? When they make an excursion against the enemy, they often spend two or three months in an arduous journey of above three hundred leagues through desert wilds. They swim across vast rivers, and long lakes more dangerous than rivers. They traverse plains of great extent, destitute both of wood and water. They sit for whole days on saddles scarce softer than wood, without having their feet supported by a stirrup. Their hands always bear the weight of a very long spear. They generally ride trotting horses, which miserably shake the rider's bones by their jerking pace. They go bareheaded amidst burning sun, profuse rain, clouds of dust, and hurricanes of wind. They generally cover their bodies with woollen garments, which fit close to the skin; but if the extreme heat obliges them to throw these off as far as the middle, their breasts, shoulders, and arms are cruelly bitten and covered with blood by swarms of flies, gad-flies, gnats, and wasps. As they always set out upon their journeys unfurnished with provisions, they are obliged to be constantly on the look out for wild animals, which they may pursue, kill, and convert into a remedy for their hunger. As they have no cups they pass the night by the side of rivers or lakes, out of which they drink like dogs. But this opportunity of getting water is dearly purchased; for moist places are not only seminaries of gnats and serpents, but likewise the haunts of dangerous wild beasts, which threaten them with sleepless nights and peril of their lives. They sleep upon the hard ground, either starved with cold, or parched with heat, and if overtaken by a storm, often lie awake, soaking in water the whole night. When they perform the office of scouts, they frequently have to creep on their hands and feet over trackless woods, and through forests, to avoid discovery; passing days and nights without sleep or food. This also was the case when they were long pursued by the enemy, and forced to hasten their flight. All these things the Abipones do, and suffer without ever complaining, or uttering an expression of impatience, unlike Europeans, who, at the smallest inconvenience, get out of humour, grow angry, and since they cannot bend heaven to their will, call upon hell. What we denominate patience is nature with them. Their minds are habituated to inconvenience, and their bodies almost rendered insensible by long custom, even from childhood. While yet children they imitate their fathers in piercing their breasts and arms with sharp thorns, without any manifestation of pain. Hence it is, that when arrived at manhood, they bear their wounds without a groan, and would think the compassion of others derogatory to their fortitude. The most acute pain will deprive them of life before it will extort a sigh. The love of glory, acquired by the reputation of fortitude, renders them invincible, and commands them to be silent.

Most of the observations I have just been making apply both to men and women, although the latter possess virtues and vices peculiar to themselves. All the Americans have a natural propensity to sloth, but I gladly pronounce the Abiponian women entirely free from this foible. Every one must be astonished at their unwearied industry. They despatch the household business with which they are daily overwhelmed, with alacrity and cheerfulness. It is their task to make clothes for their husbands and children; to fetch eatable roots, and various fruits from the woods; to gather the alfaroba, grind it, and convert it into drink, and to get water and wood for the daily consumption of the family. A ridiculous custom is in use amongst the Abipones, of making the most aged woman in the horde provide water for all domestic purposes. Though the river may be close at hand, the water is always fetched in large pitchers on horseback, and the same method is observed in getting wood for fuel. You will never hear one of these women complain of fatigue, however many cares she may have to employ her mind. A noble Spaniard had a captive Abiponian woman in his service many years, and he assured me that she was more useful and valuable to him than three other servants, because she anticipated his orders, and did her business seasonably, accurately, and quickly. They justly claim the epithet of the devout female sex. No sooner do they hear the sound of the bell than they all fly to hear the Christian religion explained, and listen to the preacher with attentive ears. They highly approve the law of Christ, because by it no husband is allowed to put away his wife, or to marry more than one. For this reason they are extremely anxious to have themselves and their husbands baptized, that they may be rendered more certain of the perpetuity of their marriage. This must be understood only of the younger women; for the old ones, who are obstinate adherers to their ancient superstitions, and priestesses of the savage rites, strongly oppose the Christian religion, foreseeing that if it were embraced by the whole Abiponian nation, they should lose their authority, and become the scorn and the derision of all. The young men amongst the Abipones, as well as the old women, greatly withstood the progress of religion; for, burning with the desire of military glory and of booty, they are excessively fond of cutting off the heads of the Spaniards, and plundering their waggons and estates, which they know to be forbidden by the law of God. Hence, they had rather adhere to the institutes of their ancestors, and traverse the country on swift horses, than listen to the words of a priest within the walls of a church. If it depended upon the old men and the young women alone, the whole nation would long since have embraced our religion.

Honourable mention has been frequently made by me of the chastity of the Abiponian women: it would be wrong to be silent upon their sobriety and temperance. It costs them much labour to prepare a sweet drink for their husbands of honey and the alfaroba: but they never even taste it themselves, being condemned to pure water the whole of their lives. Would that they as carefully abstained from strife and contentions, as they do from all strong drink! Quarrels certainly do arise amongst them, and often end in blood, upon the most trivial occasions. They generally dispute about things of no consequence, about goats' wool, as Horace expresses it, or the shadow of an ass. One word uttered by a scolding woman is often the cause and means of exciting a mighty war. The Abipones, in anger, use the following terms of reproach: Acami Lanar̂aik, you are an Indian, that is, plebeian, ignoble; Acami Lichiegar̂aik, you are poor, wretched; Acami Ahamr̂aik, you are dead. They sometimes dreadfully misapply these epithets. Who would not laugh to hear a horse, flying as quick as lightning, but which his rider wishes to incite to greater speed, called Ahamr̂aik, dead? When two women quarrel, one calls the other poor, or low-born, or perhaps lifeless. Presently a loud vociferation is heard, and from words they proceed to blows. The whole company of women crowd to the market-place, not merely to look on, but to give assistance as they shall think proper. Some defend the one, some the other. The duel soon becomes a battle-royal. They fly at each other's breasts with their teeth like tigers, and often give them bloody bites. They lacerate one another's cheeks with their nails, rend their hair with their hands, and tear the hole of the flap of the ear, into which the roll of palm-leaves is inserted. Though a husband sees his wife, and a father his daughter, bathed in blood and covered with wounds, yet they look on at a distance, with motionless feet, silent tongues, and calm eyes; they applaud their Amazons, laugh, and wonder to see such anger in the souls of women, but would think it beneath a man to take any part in these female battles. If there appears no hope of the restoration of peace, they go to the Father: "See!" say they, "our women are out of their senses again to-day. Go, and frighten them away with a musket." Alarmed at the noise, and even at the sight of this, they hasten back to their tents, but even from thence, with a Stentorian voice, repeat the word which had been the occasion of the combat, and, neither liking to seem conquered, return again and again to the market-place, and renew the fight. It seems to have been a regulation of divine Providence, that the Abiponian women should abstain from all strong liquors, for, if so furious when sober, what would they have been in a state of intoxication? The whole race of the Abipones would have been utterly destroyed.

CHAPTER XVI.

OF THE LANGUAGE OF THE ABIPONES

The multitude and variety of tongues spoken in Paraguay alone, exceeds alike belief and calculation. Nor should you imagine that they vary only in dialect. Most of them are radically different. Truly admirable is their varied structure, of which no rational person can suppose these stupid savages to have been the architects and inventors. Led by this consideration, I have often affirmed that the variety and artful construction of languages should be reckoned amongst the other arguments to prove the existence of an eternal and omniscient God. The Jesuits have given religious instructions to fourteen nations of Paraguay, and widely propagated the Christian faith, in fourteen different languages. They did not each understand them all, but every one was well acquainted with two or three, namely, those of the nations amongst whom they had lived. Of the number of these was I, who spent seven years amongst the Abipones, eleven amongst the Guaranies. The nations for whom we laboured, and for whom founded colonies, were the Guaranies, Chiquitos, Mocobios, Abipones, Tobas, Malbalaes, Vilelas, Passaines, Lules, Isistines, Homoampas, Chunipies, Mataguayos, Chiriguanes, Lenguas or Guaycurùs, Mbayas, Pampas, Serranos, Patagones, and Yaròs. Moreover, the Guichua language, which is peculiar to the whole of Peru, and very familiar to Negro slaves, to the lower orders amongst the Spaniards, and even to matrons of the higher ranks in Tucuman, was used by many of the Jesuits, both in preaching and confession. Different languages were spoken too in the towns of the Chiquitos, which were composed of very different nations. The languages of the Abipones, Mocobios, and Tobas, certainly have all one origin, and are as much alike as Spanish and Portugueze. Yet they differ not only in dialect, but also in innumerable little words. The same may be said of the Tonocotè language, in use amongst the Lules and Isistines. The language of the Chiriguanes and Guaranies, who live full five hundred leagues apart, is the same, with the exception of a few words, which may be easily learnt in the course of two or three weeks by any one who understands either of them.

Many writers upon America have interspersed sentences of the Indian languages into their histories; but, good Heavens! how utterly defective and corrupted! They have scarce left a letter unmutilated. But these writers are excusable, for they have drawn their information from corrupted sources. Without having even entered America, they insert into their journals the words of savage languages, the meaning and pronunciation of which they are totally ignorant of. Hence it is that the American names of places, rivers, trees, plants, and animals, are so wretchedly mutilated in all books, that we can hardly read them without laughter. Spanish children, by constantly conversing with Indians of their own age, imbibe a correct knowledge of the Indian languages, which, to grown-up persons, is a business both of time and labour. I have known adults who, after conversing many years with the Indians, uttered as many errors as syllables. It is difficult for a European to accustom his tongue to the strange and distorted words which the savages pronounce so fast and indistinctly, hissing with their tongues, snoring with their nostrils, grinding with their teeth, and gurgling with their throats; so that you seem to hear the sound of ducks quacking in a pond, rather than the voices of men talking. Learned men had long wished that a person who understood some American language would clearly expound the system, construction, and whole anatomy of it: and it is to comply with the desire of these persons that I am going to treat compendiously of the Abiponian language.

Most of the Americans want some letter which we Europeans use, and use some which we want. A letter of very frequent occurrence amongst the Abipones, but which we Europeans are unacquainted with, is one which has the mixed sound of R and G. To pronounce it properly, the tongue must be slided a little along the roof of the mouth, and brought towards the throat, in the manner of those persons who have a natural incapacity of pronouncing the letter R. To signify this peculiar letter of the Abipones, we have written R or G indiscriminately, but distinguished by a certain mark, thus: Laetar̂at, a son: Achibir̂aik, salt. The plural number changes R into K, thus: Laetkáte, sons. Europeans find much difficulty in pronouncing this letter, especially if it recur several times in the same word, as in Rar̂egr̂anr̂aik, a Vilela Indian. Rellar̂anr̂aǹ potròl, he hunts wild horses. Lapr̂ir̂atr̂aik, many-coloured. The Abipones can distinguish an European, however well-skilled in every other part of their language, by the pronunciation of this letter.

The Abipones use the ö, which the Paraguayrians write ë with two dots, like the French, Hungarians, and Germans: as Ahëpegak, a horse, Yahëc, my face. They make frequent use of the Greek K. They pronounce N like the Spaniards, as if the letter I was added to it: thus, Español must be pronounced Espaniol. The Abipones say Menetañi, it is within; Yoamcachiñi, the inner part is good. The legitimate pronunciation of this and other letters can only be learned vivâ voce.

Great attention must be paid to all the different accents and points, for the omission of a point, or the variation of an accent, gives a word a totally different meaning, thus: Heét, I fly; Hëët, I speak; Háten, I despise; Hateń, I hit the mark. This language abounds in very long words, consisting of ten, twenty, or more letters. The accents repeated in the same word show where the voice should be raised and where lowered: for the speech of this nation is very much modulated, and resembles singing. The accents alone are scarce sufficient to teach the pronunciation. It would not be amiss to subjoin musical notes to each of the syllables, unless a master supersedes the necessity of this artifice by teaching it vivâ voce. It may be as well to give some examples of accents. Hamihégemkiń, Debáyakaikin, Raregr̂ágremar̂achiń, Oahérkaikiń. These are names of Abipones. Grcáuagyégarigé, pity me. Oaháyegalgè, free me. Hapagrañütapagetá, you teach one another. Ñicauagrañíapegar̂algé, I intercede for thee. Hemokáchiñütápegioà, thou praisest me. Here are words of twenty letters. You will not find many monosyllables. The tall Abipones like words which resemble themselves in length.

They have a masculine and a feminine gender, but no neuter. A knowledge of the genders is to be gained by use alone. Grahaulái, the sun, is feminine with them, like the German Die Sonne. Grauèk, the moon, is masculine, as our Der Monde. Some adjectives are of both genders, as Naà, which is evil, both masculine and feminine. Neeù, good, of both genders. In others every gender has its own termination, as Ariaik, good, noble, mas. Ariayè, good, noble, fem. Cachiergaik, an old man; Cachergayè, an old woman.

The nouns have no cases. A letter prefixed to the noun sometimes indicates the case: as, Ay`m, I; M`ay`m, to me; Akami, thou; M'akami, to thee.

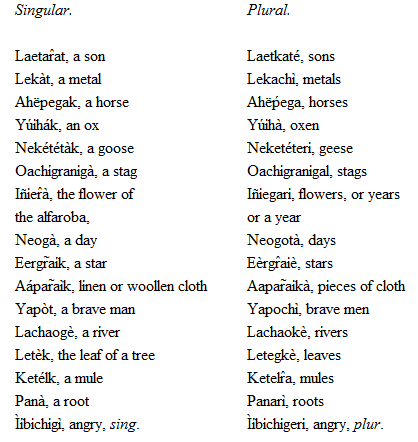

The formation of the plural number of nouns is very difficult to beginners; for it is so various that hardly any rule can be set down. I give you some examples:

From these few examples it appears that nouns ending in the same letter have different plurals. Moreover, as the Greeks, beside a plural number, have also a dual by which they express two things, so the Abipones have two plurals, of which the one signifies more than one, the other many: thus Joalé, a man. Joaleè, or Joaleèna, some men. Joalíripì, many men. Ahëpegak, a horse. Ahëpega, some horses. Ahëpegeripì, many horses.

I wonder that the Abipones have not two words for the first person plural, we, like many other American nations. The Guaranies express it in two ways: they sometimes say, ñandè, sometimes ore. The first they call the inclusive, the second the exclusive. In their prayers, addressing God, they say, We sinners, ore angaypabiyà; because God is excluded from the number of sinners. Speaking with men, they say, ñandè angaypabiyà, because those whom they address are sinners likewise, and they accordingly use the inclusive ñandè.

As they have no possessive pronouns, mine, thine, his, the want of them is supplied in every noun, by the addition or alteration of various letters. Amongst the Abipones a great difficulty is occasioned by the various changes of the letters, especially in the second person. Take these examples. Netà, a father indeterminately. Yità, my father. Gretaỳ, thine. Letà, his. Gretà, our father. Gretayi, yours. Letai, theirs.

Naetar̃at, a son, without expressing whose. Yaetr̃at, my son. Graetr̃achi, thy son. Laetr̃at, his son.

Nepèp, a maternal grandfather. Yepèp, mine. Grepepè, thine. Lepèp, his.

Naàl, a grandson. Yaàl, mine. Graalí, thine. Laàl, his.

Nenàk, a younger brother. Yenàk, mine. Grenarè, thine. Lenàk, his.

Nakirèk, a cousin german. Ñakirèk, mine. Gnakiregi, thine. Nakirek, his.

Noheletè, the point of a spear. Yoheletè, mine. Grohelichi, thine. Loheletè, his.

Natatr̃a, life. Yatatr̃a, my life. Gratatr̃e, thine. Latatr̃a, his.

But these examples are sufficient to show the multiplied variety of the second person. Amongst the Guaranies too, the possessives are affixed to the nouns, but this occasions no difficulty, because the mutation is regular: thus, Tuba, a father. Cheruba, my father. Nderuba, thine. Tuba, his. Guba, theirs. Tay̆, a son. Cheray̆, mine. Nderay̆, thine. Tay̆, his. Guay̆, theirs. Che is prefixed to nouns for the first person, and Nde for the second, without variation. Likewise in the plural they say Ñande, or Oreruba, our father. Penduba, your father. Tuba, or Guba, their father. In all other substantives these particles supply the place of possessives.

The following observation must be made on the possessive nouns of the Abipones. If they see any thing whose owner they do not know, and wish to be made acquainted with, they enquire to whom it belongs in various ways. If the object in question be animate, (even though it only possess vegetable life,) as wheat, a horse, a dog, a captive, &c. they say Cahami ledà? whose property is this? to which the other will reply, Ylà, mine. Grelè, thine. Lelà, his. On the other hand, if the thing be inanimate, as a spear, a garment, food, &c. they say Kahamì kalàm, to whom does this belong, and the other will say, Ai`m, to me. Karami, to thee. Hala`m, to him. Kara`m, to us, &c.

The pronouns of the first and second persons are subject to no mutations, on account of place or situation. Thus, Aỳm, I. Akami, thou. Aka`m, we. Akamyì, you. If alone be added, they are altered in this manner: Aỳmátarà, I alone. Akamítarà, thou alone. Akàm àkalè, we alone.

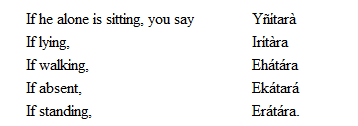

But the pronoun of the third person, he, is varied, according to the situation of the person of whom you speak. For if the object of discourse

He alone is also expressed in various ways.

They form the comparative and superlative degrees, not as in other languages, by the addition of syllables, but in a different manner. An Abipon would express this sentence. The tiger is worse than the dog, thus: the dog is not bad though the tiger be bad. Nétegink chik naà, oágan nihirenak la naà: or thus, The dog is not bad as the tiger, Netegink chi chi naà ỳágàm nihirenak. When we should say, The tiger is worst, an Abipon would say, the tiger is bad above all things, Nihirenak lamerpëëáoge kenoáoge naà: or thus, The tiger is bad so that it has no equal in badness. Nihirenak chit keoá naà. Sometimes they express a superlative, or any other eminence, merely by raising the voice. Ariaik, according to the pronunciation, signifies either a thing simply good, or the very best. If it be uttered with the whole force of the breast, and with an elevated voice, ending in an acute sound, it denotes the superlative degree; if with a calm, low voice, the positive. They signify that they are much pleased with any thing, or that they approve it greatly, by uttering with a loud voice the words Là naà! before Ariaik, or Eúrenék. Now it is bad! It is beautiful, or excellent! Nehaol means night. If they exclaim in a sharp tone, Là nehaòl, they mean that it is midnight, or the dead of the night: if they pronounce it slowly and hesitatingly, they mean that it is the beginning of the night. When they see any one hit the mark with an arrow, knock down a tiger quickly, &c. and wish to express that he is eminently dexterous, they cry with a loud voice, La yáraigè, now he knows, which, with them, is the highest commendation.