По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

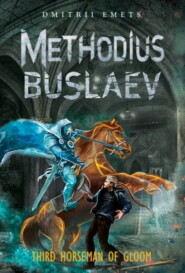

Methodius Buslaev. Ticket to Bald Mountain

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Irka chuckled. “Anyway, it wasn’t me!”

“How was it not you? Really, it was not you! Oh, no! I’m dead! I dream of that girl every day!” Fatiaitsev said and, sobbing, covered his face with his hands.

He was sobbing so credibly, with splashes and even streams of tears, that Irka even got scared and nudged Essiorh with an elbow. In response, Essiorh silently pointed a finger at Fatiaitsev’s ears. It turned out, the former clown, sobbing, did not forget to move his ears comically.

“Enough clowning around! You’re frightening the girl!” Essiorh said with displeasure.

Fatiaitsev lifted a red indignant face to the ceiling. “I’m not clowning around! I’m truly suffering! I’m a clown mime! The eternal Pierrot! And you’re the shameless Harlequin![8 - Pierrot and Harlequin are both stock characters of pantomime, Pierrot being the sad clown and Harlequin the nimble and witty servant, both pursuing the same love interest – Columbine.] No more than that!” he rumbled.

True, Fatiaitsev did not make a noise for long. He stopped playing the fool after only half a minute and invited Irka and Essiorh to dine with him. “Do you know how I live now, where this wine, smoked sausage, grapes, and other elements of aristocratic degradation come from?” he asked, nodding proudly at the table.

“You wander along Arbat in a red wig, with a red round nose on an elastic band, and sell balloons?” Essiorh smiled, knowing the correct answer but having decided to play along.

“Balloons? Nothing of the sort,” Fatiaitsev protested violently. “That phase of my life is over. Now I write speeches.”

“For the government?” Irka asked in surprise.

Fatiaitsev shook his head. “I haven’t fallen so low yet. They have their own clowns there. I compose confessions of love for romantics devoid of eloquence; tragic epitaphs to brothers lost prematurely, when those who blew them up crowded around with tears in their eyes – sincere tears, mind you!; wedding invitations; and other things. There are the unexpected orders. Recently, for example, I wrote a speech for a modest employee who wanted to ask his boss for a raise.”

“So, did he get the raise?”

“Alas, no. The boss turned out to be a tough redneck. But then my charge, in the process of studying the speech – and the speech turned out heartfelt! – started an affair with a colleague. For half a year before that, they sat almost desk to desk but didn’t even look at each other. The affair has gone quite far, and now I write excuses for the wretch, since he’s married. His wife is a rather clever woman, not easy to deceive, and now and then I rack my brain for hours concocting something fresh. Where he was and why he stayed late at work.”

Essiorh shook his head reproachfully. Fatiaitsev was on fire and shot amusing stories one after another. Already at the end of the meal, he mentioned in passing that soon he would be in hospital for surgery.

“What surgery?” Irka asked.

“Well that, no big deal. A matter of several days,” Fatiaitsev replied.

“Serious?”

The clown shook his head. “What is serious, a little thing… I had a granny, smart old woman, but thoroughly sick. I won’t tell you how many times she was under the knife, but she lived carefree the whole time. ‘Eh, Alec!’ she said. ‘Will you really protect yourself? A person dies only once, arms and legs not worn out as they should be, eyes not ruined. Isn’t it a shame? He lies in the coffin, legs are whole, arms aren’t wasted, but where’s the person – gone! Better to leave this world in pieces, but live longer!’ Well, please don’t think badly of me!”

Fatiaitsev inflated his cheeks and smacked them, making a shot louder than a pistol. Then he looked anxiously at the clock and, shouting, “Business! Business! The heart begs for peace!”[9 - This is an adaptation of It’s time, my friend (1834), a poem by Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin (1799–1837), the greatest Russian poet.] dashed away somewhere.

“Well, what do you think of Fatiaitsev? Isn’t he great?” Essiorh asked.

“Your friend is a very sad person,” said Irka.

“Who’s sad, him?” the keeper asked incredulously.

“Yes. Even when he jokes, he has sad eyes.”

“It’s probably because he’s a former clown. All clowns have sad eyes. They make others laugh, but they are not funny to themselves at all,” Essiorh said after thinking.

* * *

The room, which the keeper was proud of, turned out to be tiny. A small semicircular balcony – approximately about two steps – was attached to the window. However, according to Essiorh, it was dangerous to step out onto the balcony – it was in an unsafe state. But then the pigeons loved to visit it. Here they cooed, pecked bread, and left white autographic smudges.

“Well, here we are, home!” Essiorh said with obvious satisfaction.

On each of the four walls, the floor, and the ceiling, Irka saw a shielding rune of Light, remote like the sea, the kind drawn by small children. Irka had never seen a small room guarded with such magical care.

After shutting the door behind himself, Essiorh stuck his ear to it and listened attentively to something for a while. Then he approached the window and looked outside for a long time. He breathed on the glass and with the long nail of his little finger drew a line of strange signs on it. Some of them immediately melted, others were imprinted on the glass, as if burnt on it forever.

Essiorh must have been satisfied with the result. He relaxed and turned to Irka. “And now we can talk business! I’m sure that Gloom would very much want to acquire this…” the keeper said, nodding to a small rectangular object resting against the wall and covered with a blanket. Before pulling off the blanket, Essiorh quickly glanced at all the runes. Then he leaned over, pulled the blanket by the edge, and stepped back.

Irka realized that before her was a portrait. She saw the face of a boy of about eight. His dark hair was naturally curly. Dressed in a white shirt with an unbuttoned collar, he looked calmly from the portrait, leaning on a sabre in its scabbard. For the aforementioned age, the boy’s face was rather too clever and mocking. It was noticeable that he was tired of posing, bored of holding the sabre, and secretly wanted to stick his tongue out at the artist. The portrait must have been painted not on the best canvas and with poor paint. A network of small cracks had already managed to cover its outside.

“Who’s this?” Irka asked.

“Matvei Bagrov, son of the Orlovsky landowner Theodore Bagrov,” Essiorh replied.

“Is this portrait magical?” Irka asked.

The keeper shook his head. “Ordinary. Until the invention of photography, many artists travelled to estates of the gentry, ready to paint everything that was ordered. Portraits of masters, romantic mills, favourite horses, dogs… Then photography ruined everything, and the craft gradually disappeared.”

“Where did you get this portrait?” Irka asked.

Essiorh smiled. “You’ll be surprised. I stole it today from the restoration studio!” he said.

“YOU STOLE IT?”

“Well, why repeat? I told you: I stole it. Everything was done cleanly, with minimal use of magic. I teleported, making use of the absence of the restorers, covered the video camera with a sock, took the portrait together with its frame, and that was it. A matter of two minutes. I spent much more time destroying all the reproductions of this picture and the images stored in the catalogs. Fortunately, there turned out to be not too many of them. The portrait isn’t the most well-known and the majority of the time it was gathering dust in storage.”

“But why did you steal it?”

Essiorh looked at Irka patiently. “Two options. Select one. First: in order to sell it on the flea market and purchase an idiot’s pink dream – a Kawasaki Ninja ZX-R motorcycle. Second: so that Gloom or dark wizards wouldn’t get it.”

“The second,” said Irka.

“I would choose the first. Indeed, awfully attractive. Unfortunately, you’re right, the second,” Essiorh confirmed with disappointment.

“But why is it so important that Gloom doesn’t know what the boy looks like? The portrait is old, and the one in it is long gone,” Irka said, looking with regret at the clever and lively face in the portrait.

The keeper glanced at her with polite surprise. “I wouldn’t rush to conclusions. Do you know for sure that he’s dead? Do you have proof? Is there something that I don’t know?” he asked greedily.

“No, but if one simply estimates the date, then…” Irka began.

“So I thought, you don’t have proof,” Essiorh interrupted her severely. “When a moronoid (let it even be a former one) goes into a standoff, he immediately begins to refer to arithmetic… It’s a well-known practice! Perhaps you’ll even say that three plus three is six?”

“How much?”

“This rule is correct only if you count bricks. But if we, for example, take three kindnesses and three tomatoes and add them up, will this also be six?”

“Excuse me. You’re probably right. I’m a bad valkyrie,” said Irka.

“Well, well…” Essiorh instantly thawed. “I’m not a good keeper, crazy about motorcycles and renting a room in a communal dwelling with payment of euphoric tears! On the whole, the reason I showed you the portrait is that all this is terribly important. But now listen to me. I’ll tell you everything I know about Matvei Bagrov…”

“How was it not you? Really, it was not you! Oh, no! I’m dead! I dream of that girl every day!” Fatiaitsev said and, sobbing, covered his face with his hands.

He was sobbing so credibly, with splashes and even streams of tears, that Irka even got scared and nudged Essiorh with an elbow. In response, Essiorh silently pointed a finger at Fatiaitsev’s ears. It turned out, the former clown, sobbing, did not forget to move his ears comically.

“Enough clowning around! You’re frightening the girl!” Essiorh said with displeasure.

Fatiaitsev lifted a red indignant face to the ceiling. “I’m not clowning around! I’m truly suffering! I’m a clown mime! The eternal Pierrot! And you’re the shameless Harlequin![8 - Pierrot and Harlequin are both stock characters of pantomime, Pierrot being the sad clown and Harlequin the nimble and witty servant, both pursuing the same love interest – Columbine.] No more than that!” he rumbled.

True, Fatiaitsev did not make a noise for long. He stopped playing the fool after only half a minute and invited Irka and Essiorh to dine with him. “Do you know how I live now, where this wine, smoked sausage, grapes, and other elements of aristocratic degradation come from?” he asked, nodding proudly at the table.

“You wander along Arbat in a red wig, with a red round nose on an elastic band, and sell balloons?” Essiorh smiled, knowing the correct answer but having decided to play along.

“Balloons? Nothing of the sort,” Fatiaitsev protested violently. “That phase of my life is over. Now I write speeches.”

“For the government?” Irka asked in surprise.

Fatiaitsev shook his head. “I haven’t fallen so low yet. They have their own clowns there. I compose confessions of love for romantics devoid of eloquence; tragic epitaphs to brothers lost prematurely, when those who blew them up crowded around with tears in their eyes – sincere tears, mind you!; wedding invitations; and other things. There are the unexpected orders. Recently, for example, I wrote a speech for a modest employee who wanted to ask his boss for a raise.”

“So, did he get the raise?”

“Alas, no. The boss turned out to be a tough redneck. But then my charge, in the process of studying the speech – and the speech turned out heartfelt! – started an affair with a colleague. For half a year before that, they sat almost desk to desk but didn’t even look at each other. The affair has gone quite far, and now I write excuses for the wretch, since he’s married. His wife is a rather clever woman, not easy to deceive, and now and then I rack my brain for hours concocting something fresh. Where he was and why he stayed late at work.”

Essiorh shook his head reproachfully. Fatiaitsev was on fire and shot amusing stories one after another. Already at the end of the meal, he mentioned in passing that soon he would be in hospital for surgery.

“What surgery?” Irka asked.

“Well that, no big deal. A matter of several days,” Fatiaitsev replied.

“Serious?”

The clown shook his head. “What is serious, a little thing… I had a granny, smart old woman, but thoroughly sick. I won’t tell you how many times she was under the knife, but she lived carefree the whole time. ‘Eh, Alec!’ she said. ‘Will you really protect yourself? A person dies only once, arms and legs not worn out as they should be, eyes not ruined. Isn’t it a shame? He lies in the coffin, legs are whole, arms aren’t wasted, but where’s the person – gone! Better to leave this world in pieces, but live longer!’ Well, please don’t think badly of me!”

Fatiaitsev inflated his cheeks and smacked them, making a shot louder than a pistol. Then he looked anxiously at the clock and, shouting, “Business! Business! The heart begs for peace!”[9 - This is an adaptation of It’s time, my friend (1834), a poem by Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin (1799–1837), the greatest Russian poet.] dashed away somewhere.

“Well, what do you think of Fatiaitsev? Isn’t he great?” Essiorh asked.

“Your friend is a very sad person,” said Irka.

“Who’s sad, him?” the keeper asked incredulously.

“Yes. Even when he jokes, he has sad eyes.”

“It’s probably because he’s a former clown. All clowns have sad eyes. They make others laugh, but they are not funny to themselves at all,” Essiorh said after thinking.

* * *

The room, which the keeper was proud of, turned out to be tiny. A small semicircular balcony – approximately about two steps – was attached to the window. However, according to Essiorh, it was dangerous to step out onto the balcony – it was in an unsafe state. But then the pigeons loved to visit it. Here they cooed, pecked bread, and left white autographic smudges.

“Well, here we are, home!” Essiorh said with obvious satisfaction.

On each of the four walls, the floor, and the ceiling, Irka saw a shielding rune of Light, remote like the sea, the kind drawn by small children. Irka had never seen a small room guarded with such magical care.

After shutting the door behind himself, Essiorh stuck his ear to it and listened attentively to something for a while. Then he approached the window and looked outside for a long time. He breathed on the glass and with the long nail of his little finger drew a line of strange signs on it. Some of them immediately melted, others were imprinted on the glass, as if burnt on it forever.

Essiorh must have been satisfied with the result. He relaxed and turned to Irka. “And now we can talk business! I’m sure that Gloom would very much want to acquire this…” the keeper said, nodding to a small rectangular object resting against the wall and covered with a blanket. Before pulling off the blanket, Essiorh quickly glanced at all the runes. Then he leaned over, pulled the blanket by the edge, and stepped back.

Irka realized that before her was a portrait. She saw the face of a boy of about eight. His dark hair was naturally curly. Dressed in a white shirt with an unbuttoned collar, he looked calmly from the portrait, leaning on a sabre in its scabbard. For the aforementioned age, the boy’s face was rather too clever and mocking. It was noticeable that he was tired of posing, bored of holding the sabre, and secretly wanted to stick his tongue out at the artist. The portrait must have been painted not on the best canvas and with poor paint. A network of small cracks had already managed to cover its outside.

“Who’s this?” Irka asked.

“Matvei Bagrov, son of the Orlovsky landowner Theodore Bagrov,” Essiorh replied.

“Is this portrait magical?” Irka asked.

The keeper shook his head. “Ordinary. Until the invention of photography, many artists travelled to estates of the gentry, ready to paint everything that was ordered. Portraits of masters, romantic mills, favourite horses, dogs… Then photography ruined everything, and the craft gradually disappeared.”

“Where did you get this portrait?” Irka asked.

Essiorh smiled. “You’ll be surprised. I stole it today from the restoration studio!” he said.

“YOU STOLE IT?”

“Well, why repeat? I told you: I stole it. Everything was done cleanly, with minimal use of magic. I teleported, making use of the absence of the restorers, covered the video camera with a sock, took the portrait together with its frame, and that was it. A matter of two minutes. I spent much more time destroying all the reproductions of this picture and the images stored in the catalogs. Fortunately, there turned out to be not too many of them. The portrait isn’t the most well-known and the majority of the time it was gathering dust in storage.”

“But why did you steal it?”

Essiorh looked at Irka patiently. “Two options. Select one. First: in order to sell it on the flea market and purchase an idiot’s pink dream – a Kawasaki Ninja ZX-R motorcycle. Second: so that Gloom or dark wizards wouldn’t get it.”

“The second,” said Irka.

“I would choose the first. Indeed, awfully attractive. Unfortunately, you’re right, the second,” Essiorh confirmed with disappointment.

“But why is it so important that Gloom doesn’t know what the boy looks like? The portrait is old, and the one in it is long gone,” Irka said, looking with regret at the clever and lively face in the portrait.

The keeper glanced at her with polite surprise. “I wouldn’t rush to conclusions. Do you know for sure that he’s dead? Do you have proof? Is there something that I don’t know?” he asked greedily.

“No, but if one simply estimates the date, then…” Irka began.

“So I thought, you don’t have proof,” Essiorh interrupted her severely. “When a moronoid (let it even be a former one) goes into a standoff, he immediately begins to refer to arithmetic… It’s a well-known practice! Perhaps you’ll even say that three plus three is six?”

“How much?”

“This rule is correct only if you count bricks. But if we, for example, take three kindnesses and three tomatoes and add them up, will this also be six?”

“Excuse me. You’re probably right. I’m a bad valkyrie,” said Irka.

“Well, well…” Essiorh instantly thawed. “I’m not a good keeper, crazy about motorcycles and renting a room in a communal dwelling with payment of euphoric tears! On the whole, the reason I showed you the portrait is that all this is terribly important. But now listen to me. I’ll tell you everything I know about Matvei Bagrov…”