England and Germany

In Poland there were well over 500,000 German colonists, besides a large number of new-comers, whose unwritten “privileges” included, as we saw, occasional permission to their young men liable to serve a few weeks annually in the ranks of the German army to discharge that duty under German officers in Russian Poland! In the Ukraine and the most fertile districts of the Volga basin hundreds of thousands of Germans lived, throve, and upheld the traditions as well as the language of the Fatherland, under the eyes of tolerant local authorities.

Hard by old Novgorod, the once famous Russian republic and cradle of the Russian State, a number of German colonists settled some 150 years ago. The population of two of these settlements numbers several thousand souls, descendants of the original settlers, in the fourth and fifth generation. They had had time enough, one would think, during that century-and-a-half to assimilate Russian ways and to acquire a thorough knowledge of the Russian tongue. Well, these colonists do not speak the language of the country in which they and their forbears have been living for over 150 years! They still consider themselves German, and if you ask them who their sovereign is they answer unhesitatingly – Kaiser Wilhelm! During Russia’s recent military reverses, which threatened for a time to culminate in the capture of Riga, and possibly of Petrograd as well, these parasites in the body politic of Russia displayed their joy in various unseemly ways, which aroused the indignation of their Slav neighbours. In one of their schools the Russian visiting authorities were received with demonstrations of hostility. It is usual for the portrait of the Russian Tsar to be set up in every school in the Empire. In one of these educational establishments it was discovered in the lavatory with the eyes gouged out.

Long before this war Berlin had become alive to the importance of these colonies as factors in the work of pacific interpenetration and political propaganda. Wandering teachers from the Fatherland were accordingly sent among them to link them up with their brethren at home, and fan the embers of patriotism which long residence in the Tsardom had not quenched. Little by little, the political fruits of these apostolic labours began to show themselves: the colonists, whose main preoccupation had been to occupy the most fertile soil in the district, began to take over the approaches to Russia’s strategic plans, and to display an absorbing interest in Russian politics. Several Zemstvos fell into their hands, and were practically controlled by them, and they contrived to gain considerable influence in the elections to the Duma.

The chance of a useful part for these German colonies to perform having thus unexpectedly arisen on the horizon, they seized it with promptitude and utilized it with the thoroughness that characterizes their race. The numbers prosperity, and influence of the colonies grew rapidly. Land that had belonged to the Russian peasantry was taken over by the foreign parasites, and while the Tsar’s Minister, were toiling and moiling to transport hundreds of thousands of Russian husbandmen and their families in search of land beyond the Ural Mountains to the virgin forests of Eastern Siberia, there in the very heart of European Russia were hundreds of thousands of intruders, who, with the help of their German Colonial banks, were acquiring additional tracts of land from which their native owners had been ousted.

I pointed out this anomaly over and over again, and long before the war I described it in review articles. The well-known German Professor, Hans Delbrück, replied shortly afterwards, in the Contemporary Review,38 denying point-blank the truth of my statements, which were drawn from official sources, and confirmed by the evidence of my senses. For I had visited several of the colonies in question. Besides these German settlements, there had also been a number of German industrial and commercial establishments in the Empire which, at first nowise harmful, were afterwards taken in hand by emissaries from Berlin, linked up together, affiliated to one or other of the great financial houses of Germany, and transformed into redoubtable instruments of Teuton domination. Capital was subscribed, syndicates were formed, railway-building and electro-technical industries were organized, Russia’s railways policy modified, and metallurgical works were monopolized by the Germans. Here again financial institutions discharged the functions of motive power. At the beginning, about thirty million roubles were subscribed for the creation of banks, and by dint of push, importunity, secret influence and intrigue, these institutions received on deposit the savings of the Russian peasant, merchant, landowner, and official, which finally mounted up to several hundreds of millions. With this money they were enabled to control the markets and constrain Russian institutions and individuals to bow to their will.

Contracts in Russia were appropriately drafted in the German language, being directed to the promotion of German interests. Incipient and even long-established Russian firms were either killed by unfair competition or compelled to enter the syndicates and forego their national character. Inventions and new appliances were tested, plagiarized, and employed in the service of the Fatherland. And while preparing for the war which was to set Germany above the nations —Deutschland über Alles– these syndicates followed the policy dictated from Berlin, sowed discord between Russian firms and various State departments, organized strikes and paid the strikers in competing establishments, and thus deprived the Russian State of industrial organs on which it would necessarily have to rely in war-time. To give but one example of this cleverly devised attack, the cotton industry of the Tsardom was in the hands of the Germans when war was declared. Another of the most important groups of Russian industries is that of naphtha. When this precious liquid is dear, many of the lesser works have to close; when it is cheap, even small industrial enterprises are able to go on working. By way of obtaining complete control of this vital element of Russia’s industrial life, the Deutsche Bank went to work to form a syndicate, had a number of private wells bought up, united them in one, acquired numerous shares in Russian oil companies, and had the manager of another German bank – the well-known Disconto Gesellschaft – made a member of the Board of the Russian Nobel Company.

One of the results of this ingenious deal was a sharp rise in the prices of all the products and some of the by-products of naphtha. The increase continued at an alarming rate, filling the pockets of the German shareholders, whose syndicates received the oil at cost price for their own consumption, while Russian firms were forced to acquire it at the market value or to shut down their works. Amongst the worst sufferers from these anti-Russian tactics were the steam-navigation companies of the Volga, which had jealously warded off all attempts to germanize them.

In conditions as restrictive as these, it is well-nigh impossible for Russian industry to hold its own, much less prosper and grow. And only the most vigorous and best-organized enterprises in the Empire, like that of the Morozoffs in Moscow, managed to pursue their way unscathed. In Russian Poland, where textile industries flourished, and the total annual production was valued at 294,000,000 roubles, over one-third of these industries belonged to the Germans, whose yearly output amounted to more than one-half of the grand total, i. e., to 150,000,000 roubles.39 In all these industrial and commercial campaigns the German prime movers had carried out their operations more or less openly. But where interests affecting the defences of the Empire were concerned, caution was the first condition of success, and, as usual, the Teutons proved supple and adaptable. By way of levying an attack against the shipbuilding industry, they pushed shaky Russian concerns into the foreground, while studiously keeping themselves out of view. Thus in one case new Russian banks were founded, and old ones in a state of decay were revived by means of German capital and encouraged to form a syndicate with the Nikolayeffsky shipbuilding works and certain foreign banks. An official inquiry, presided over by Senator Neidhardt, lately revealed the significant fact that each firm of this syndicate had bound itself to demand identical prices for the construction of Russian ships, and under no circumstances to abate an iota of the demand. And it was further agreed that these prices should be so calculated as to yield to the members of the syndicate one hundred per cent. profit.

This allegation is not a mere inference, nor a rumour. It is an established fact. Neither is the proof circumstantial; it consists of the original agreement in writing signed by the authorized representatives of the institutions concerned. The data were laid before the members of the Russian Duma by A. N. Khvostoff.40 Thus the Russian peasant is taxed for the creation of a fleet, and the Duma votes an initial credit of, say, 500,000,000 roubles for the purpose. And if the shipbuilding companies and their financial bankers were honest the aim could be achieved. But in the circumstances what it comes to is that the nation must pay 500,000,000 more, in order to get what it wants. And this tax of a hundred per cent. is levied by German parasites on the Russian people. One might scrutinize the history of corruption in every country of Europe without finding anything to beat this Teutonic device, which at the same time gratified the cupidity of the money-makers and dealt a stunning blow at the Russian State. Half of the shares of the celebrated Putiloff munitions factory are said to have belonged to the Austrian Skoda Works.

At the outset of the present war, when Russia’s needs were growing greater and more pressing, the works controlled by Germans and Germany’s agents diminished their output steadily. In lieu of turning out, say, 30,000 poods of iron they would produce only 5,000, and offer instead of the remainder verbal explanations to the effect that lack of fuel or damage to the machinery had caused the diminution. Again, one of these ubiquitous banks buys a large amount of corn or sugar, but instead of having it conveyed to the districts suffering from a dearth of that commodity, deposits it in a safe place and waits. In the meantime prices go up until they reach the prohibition level. Then the bank sells its stores in small quantities. The people suffer, murmur, and blame the Government. Nor is it only the average man who thus complains. In the Duma the authorities have been severely blamed for leaving the population to the mercy of those money-grubbers whom German capital and Russian tribute are making rich. “Averse to go to the root of the matter,” one Deputy complained, “the Government punishes a woman who, on the market sells a herring five copecks dearer than the current price, yet at the same time it permits the Governors to promulgate their own arbitrary laws regulating imports and exports from their own provinces. In this way Russia is split up into sixty different regions, each one of which pursues its own policy unchecked.”

The importance of the rôle played by the banks financed by German capital in Russia can hardly be overstated. They advance money on the crops and take railway and steamship invoices as guarantees – they are centres of information respecting everybody who resides and everything that goes on in the district and the province. I write with personal knowledge of their working, for I watched it at close quarters in the Volga district and the Caucasus with the assistance of an experienced bank manager. Their political influence can be far-reaching, and the services which they are enabled to render to the Fatherland are appreciable. And they rendered them willingly. As extenders of Germany’s economic power in the Empire they merited uncommonly well of their own kindred. Thus of Russia’s total imports in the year 1910, which were valued at 953,000,000 roubles, Germany alone contributed goods computed at 440,000,000. These consisted mainly of raw cotton, machinery, prepared skins, chemical products, and wool.

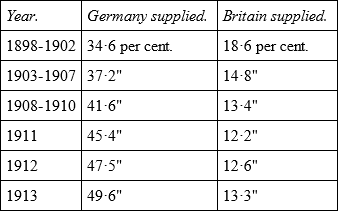

How steadily our rivals kept ousting the British out of Russian markets by those means may be gathered from the following comparative tables. The percentage of Russia’s requirements supplied by the two competing nations varied, during the fifteen years between 1898 and 1913, as follows —

In the year 1901 Germany supplied 31 per cent. of the total value of Russia’s imports; in 1905 her contribution was 42 per cent.; and the increase went steadily forward, reaching over 50 per cent. in the year 1913. If we add to this the net profits of German industrial and commercial undertakings in the Russian Empire, we may form a notion of the appropriateness of the comparison which likened the Tsardom to a vast German colony. The entire economic system of the country was rapidly approaching the colonial type. And to these economic results one should add the political.

It is fair to assume that at the outset the main motive of this industrial invasion was the quest of commercial profit. Subconsciously political objects may have been vaguely present to the minds of these pioneers, as indeed they have ever been to the various categories of German emigrants in every land, European and other. But in the first instance the creation of German industries in Russia was part of a deliberate plan to elude the heavy tariffs on manufactured goods. It has been aptly described by an Italian publicist41 as legal contraband, and it supplies us with a striking example of German enterprise and tenacity. It attained its object fully. About three-fourths of the textile and metallurgical production in the Tsardom, the entire chemical industry, the breweries, 85 per cent. of the electrical works and 70 per cent. of gas production were German. And of the capital invested in private railways no less than 628,000,000 roubles belongs to Germans. Even Russian municipalities were wont to apply to Germany for their loans, and of the first issues of thirty-five Russian municipal loans no less than twenty-two were raised in the Fatherland.

The necessity of waging war against this potent enemy within the gates intensified Russia’s initial difficulties to an extent that can hardly be realized abroad, and was a constant source of unexpected and disconcerting obstacles. Some time before the opening of the war, a feeling of restiveness, an impulse to throw off the German yoke, had been gradually displaying itself in the Press, in commercial circles, and in the Duma. These aspirations and strivings were focussed in the firm resolve of the Russian Government, under M. Kokofftseff, to refuse to renew the Treaty of Commerce which was enabling Germany to flood the Empire with her manufactures and to extort a ruinous tribute from the Russian nation. Two years more and the negotiations on this burning topic would have been inaugurated, and there is little doubt in my mind – there was none in the mind of the late Count Witte – that the upshot of these conversations would have been a Russo-German war. For there was no other less drastic way of freeing the people from the domination of German technical industries and capital, and the consequent absorption of native enterprise.

When diplomatic relations were broken off, and war was finally declared, Germany was already the unavowed protectress of Russia. And when people point, as they frequently do, to the war as the greatest blunder ever committed by the Wilhelmstrasse since the Fatherland became one and indivisible, I feel unable to see with them eye to eye. Seemingly it was indeed an egregious mistake, but so obvious were the probable consequences which made it appear so that even a German of the Jingo type would have gladly avoided it had there not been another and less obvious side to the problem. We are not to forget that in Berlin it was perfectly well known that Russia was determined to withdraw from her Teutonic neighbour the series of one-sided privileges accorded to her by the then existing Treaty of Commerce, and that this determination would have been persisted in, even at the risk of war. And for war the year 1914 appeared to be far more auspicious to the German than any subsequent date.

Handicapped by these foreign parasites who were systematically deadening the force of its arm, the Russian nation stood its ground and Germany drew the sword.

Improvisation – the worst possible form of energy in a war crisis – was now the only resource left to the Tsar’s Ministers. And the financial problems had first of all to be faced. In this, as in other spheres, the country was bound by and to Germany, so that the task may fairly be characterized as one of the most arduous that was ever tackled by the Finance Minister of any country – even if we include the resourceful Calonne. And M. Bark, who had recently come into office, was new not only to the work, but also to the politics of finance in general. Happily, his predecessor, who, whatever his critics may advance to the contrary, was one of the most careful stewards the Empire has ever possessed, had accumulated in the Imperial Bank a gold reserve of over 1,603,000,000 roubles, besides a deposit abroad of 140,720,000 roubles. Incidentally it may be noted that no other bank in the world has ever disposed of such a vast gold reserve.

Although one of the richest countries in Europe, Russia’s wealth is still under the earth, and therefore merely potential. Her burden of debt was heavy. For at the outbreak of the war the disturbing effects of the Manchurian campaign and its domestic sequel, which had cost the country 3,016,000,000 roubles, had not yet been wholly shaken off. And, unlike her enemy, Russia had no special war fund to draw upon. As the national industries were unable to furnish the necessary supplies to the army, large orders had to be placed abroad and paid for in gold. At the same moment Russia’s export trade practically ceased, and together with it the one means of appreciably easing the strain. The issue of paper money in various forms was increased, loans were raised, private capital was withdrawn from the country, various less abundant sources of public revenue vanished, and the favourable balance of trade dropped from 442,000,000 roubles to 85,500,000. Germany, on the other hand, possessed her war fund, in addition to which she had levied a property tax of a milliard marks a year before the outbreak of hostilities; she further drew in enormous sums in gold from circulation, and generally mobilized her finances systematically.

But Russia was compelled to improvise, to make bricks without straw. Her war on a front of two thousand versts long had to be waged with whatever materials happened to be available. Japan – who, I have little doubt, will be found at the close of the great struggle to have benefited largely by her pains – exerted herself to provide munitions for her new friend and ally. The United States, Great Britain and France also contributed their quota. For many of these orders placed abroad gold had to be exported, and as Russia has no other natural way of importing gold but by selling corn, which there were no means of transporting, a sensible depreciation of the rouble resulted. Great Britain and France have also had to make heavy purchases abroad for their military needs, but these two countries can still export wares extensively and keep the payments in gold within certain limits. Even Italy receives a noteworthy part of her annual revenue in the shape of emigrants’ remittances from abroad. But once Russia’s gates were closed and her corn had to remain in the granaries, elevators, or at railway stations, the shortage in her revenue became absolute. During the first three months of the year 1915 the value of Russian exports over the Finnish frontier and the Caucasian coast of the Black Sea was only 23,000,000 roubles, showing a falling off of about 93 per cent., as compared with the worth of the produce exported during the corresponding three months of the preceding year.

It is a curious fact that part of this reduced trade continued to be carried on with Germany for months after the war had begun. A Russian publicist has remarked that at the opening of the campaign the voice of the nation was heard saying: “Corn we have in plenty, and vegetables and salt. It is we who feed Europe. Germany will therefore starve without our corn. Our armies may retreat, but our corn will go with them; and the more the Germans advance into Russia, the further they are away from their bread.” And in this the average Russian saw a pledge of victory. But before six months had lapsed, the everyday man grew indignant. For he learned that his corn was being conveyed through Finland and Sweden into Germany, and in such vast quantities as had never before been heard of. Here is a street scene illustrative of this traffic and the feelings it aroused. A long string of carts laden with flour blocks in one of the Petrograd streets leading to a bridge over the Neva; a General walking with his wife stops one of the drivers and asks: “Wherever are you taking the flour to?” “Where do you suppose? Sure we’re taking it to the Germans. We have to feed the creatures. They are a bit faint.” “There you see!” exclaimed the General to his wife; “didn’t I tell you? And every morning without fail the same long line of carts blocks the streets while our corn is being taken to the Germans!”42 It is to be feared that this commerce has not yet wholly ceased. For the Russians, like ourselves, are considerate of the Germans.

That that story of trading with the enemy is no idle anecdote is evident from the circumstance, based on official Russian statistics, that during ten months from August to May, while the war was being waged relentlessly between the two empires, Russia bought from Germany no less than 36,000,000 roubles’ worth of manufactures. How much the Central Empires purchased from Russia, I am unable to say. That commerce is one of the almost inevitable consequences of improvisation and one of the most sinister. Some months after the outbreak of the war the Imperial Government levied a duty of a hundred per cent. on all commodities coming from Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. That was assumed to be a prohibitive tariff. But it failed to keep out imports from the Fatherland. In the one month of April 1915, Germany sent 3,000,000 roubles’ worth of manufactured goods into Russia, and in May 2,500,000 roubles’ worth. And the Allied Press was then descanting on the stagnation in German trade and the starvation of the German people. The explanation of this anomaly lies in the unforeseen and enormous scarcity and rise of prices in the home markets. Some metal wares – for instance, various kinds of instruments and of wire appliances, etc. – are not to be had in Russia for love or money, consequently a hundred per cent. duty is but a heavy tax paid by the consumer, not an effective prohibition.43 Since then, I am assured, the Government has adopted stringent measures which some people believe to have put an end to that form of trading with the enemy.

It is hard for foreigners to realize the plight to which Russia has been reduced by the closing of her gates. As the Nile waters were the source of Egypt’s prosperity, so the abundant Russian harvests constitute the life-giving ichor which flows in the veins of the Russian nation. Without superfluous corn for exportation, the State would be unable to meet its obligations, maintain its solvency, or provide the motive power of progress. The exportation of agricultural produce was the fountain head not only of Russia’s material well-being, but of her moral and cultural evolution: everything, in a word, was dependent upon plentiful harvests and extensive sales of cereals abroad. And, suddenly, the gates were closed, the corn was stored, and the nation left without its revenue. Nobody but a Russian, or one who has lived long in the country, can realize fully all that this tremendous blow connotes. Parenthetically, it may be remarked that it adds a motive, and one of the most potent, to those which inspire the heroic sacrifices of the people, quickening the flame of devotion to their Allied cause. Russia is now literally fighting for her own liberty, for escape from the iron circle that shuts her off from the sea, and isolates her from the western world in which it is her ambition and her mission to play a helpful part.