По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

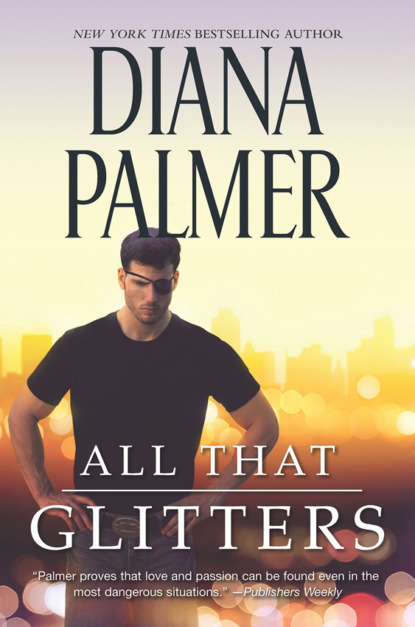

All That Glitters

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Ivory was going to escape, though. She was going to get away from the smothering dependence of her mother and the contemptuous attitude of her community at last! She was going to make a name for herself. Then, one day, she’d come back here dressed in furs and glittering with diamonds, and then the people who’d made fun of her would see that she wasn’t worthless!

The late-model Ford stopped at the front gate, raising a cloud of dust on the farm road. Their neighbor, a middle-aged man in a suit, leaned across and pushed the door open.

“Hop in, girl, I’m late for my flight already,” he said kindly.

“Hello, Bartley,” Marlene said sweetly, leaning in the window after Ivory had closed the door. “My, don’t you look handsome today!”

Bartley smiled at her. “Hello, honey. You look pretty good yourself.”

“Come over for a drink when you have a minute,” she invited. “I’m going to be all alone now that my daughter’s deserting me.”

“Mother,” Ivory protested miserably.

“She thinks she wants to be a fashion designer. It doesn’t bother her in the least to leave me out here all alone with nobody to look after me if I get sick,” Marlene said on a sigh.

“You have the Blakes and the Harrises,” Ivory reminded her, “just up the road. And you’re perfectly healthy.”

“She likes to think so,” Marlene told Bartley. “Children can be so ungrateful. Now, you be sure to write, Ivory, and do try to stay out of trouble, because other people won’t be as understanding as I am about...well, about money disappearing.”

Ivory went red in the face. She’d never been in trouble, but her mother had most of the local people convinced that her daughter stole from her and attacked her. Ivory had never been able to contradict her successfully, because Marlene had a way of laughing and agreeing with her while her eyes made a lie of everything she said. At least she’d get a chance to start over in Houston.

“I don’t steal, Mother,” Ivory declared tensely.

Marlene smiled sweetly at Bartley and rolled her eyes. “Of course you don’t, darling!”

“We’d better go,” Bartley said, uncomfortably restraining himself from checking to make sure his wallet was still in his hip pocket. “See you soon, Marlene.”

“You do that, Bartley, honey,” she drawled. She patted Ivory’s arm. “Be good, dear.”

Ivory didn’t say a word. Her mouth was tightly closed as the car pulled away. Her last sight of her mother was bittersweet, as she thought of all the pain and humiliation she’d suffered and how different everything could have been if her mother had wanted a child in the first place.

Houston might not be perfect, but it would give Ivory a chance at a career and a brighter future. Her mother wouldn’t be there to criticize and demean her. She would assume a life of class and style that would make her forget that she’d ever lived in Harmony, Texas. Once she made her way to the top, she thought, she’d never have to look back again.

CHAPTER ONE (#u74fe02ea-31e9-5cf5-b2a0-fb2b09030f32)

THE NOVEMBER AIR was brisk and cold. The stark streetlights of the Queens neighborhood wore halos of frosty mist. The young woman, warm in her faded tweed overcoat and a white beret, sat huddled beside a small boy on the narrow steps of an apartment house that had been converted into a shelter for the homeless. She looked past the dingy faces of the buildings and the oil-stained streets. Her soft gray eyes were on the stars she couldn’t see. One day, she promised herself, she was going to reach right up through the hopelessness and grab one for herself. In fact, she was already on the way there. She’d won a national contest during her last month of design school in Houston, and first prize was a job with Kells-Meredith, Incorporated, a big clothing firm in New York City.

“What are you thinking about, Ivory?”

She glanced down at the small, dark figure sitting at her side. His curly brown hair was barely visible under a moth-eaten gray stocking cap. His jacket was shabbier than her tweed coat and his shoes were stuffed with cardboard to cover the holes in the soles. A tooth was missing where his father had hit him in a drunken rage a year or so before the family had lost their apartment. It was a permanent tooth, and it wouldn’t grow back. But there was no money for cosmetic dentistry. There wasn’t even enough money to fill a cavity.

“I’m thinking about a nice, warm room, Tim,” she said. She slid an affectionate arm around him and hugged him close for warmth. “Plenty of good food to eat. A car to drive. A new coat...a jacket for you,” she teased, and hugged him closer.

“Aw, Ivory, I don’t need a coat. This one’s fine!” His black eyes twinkled as he smiled up at her.

She remembered that smile from her first day as a volunteer at the homeless shelter, because Tim had been the first person she’d seen when she came with her friend Dee, who already worked there. Ivory had not been eager to offer her services at first, because the place brought back memories of the poverty she’d endured as a child in rural Texas. But her prejudice hadn’t lasted long. When she saw the people who were staying at the shelter, her compassion for them overcame her own bitterness.

Tim had been sitting on these same steps that first day. He and his mother had been staying at the homeless shelter along with his two sisters. It was a cold day and he wore only a torn jersey jacket. Ivory had sat down and talked with him while she waited for Dee. Afterward, when Dee had asked casually if Ivory would like to volunteer a day a week to work there with her, she had agreed. Now, she almost always found Tim waiting for her when she came on Saturdays. Sometimes she brought him candy, sometimes she had a more useful present, such as a pair of mittens or a cap.

Tim’s mother loved him and did all she could for him; but she also had a toddler and a nursing baby, and her situation, like that of so many, was all but hopeless. She had a low-paying job and the shelter did, at least, provide a home.

“I would like a room,” Tim mused, interrupting her thoughts. He’d propped his face in his hands and was dreaming. “And a cat. They don’t let us have cats at the shelter, you know, Ivory.”

“Yes, I know.”

“I made a new friend today,” he said after a companionable silence had passed.

“Did you?”

“He stays at the shelter sometimes. His name’s Jake.” He sighed. “He used to be a bundle boy in a manufacturing company. What’s a bundle boy, Ivory?”

“Someone who carries bundles of cut cloth to be sewn,” she explained. She worked in the fashion sector. It wasn’t the job she’d dreamed of, but it paid her way.

“Well, the place he worked closed down and they moved his job to Mexico,” Tim told Ivory. “He can’t get another job on account of he can’t read and write. He shoots up.”

Her arm around him tightened. “I hope you don’t think that’s cool,” she said.

He shook his head. “I wouldn’t do that. My mama says it’s nasty and you can get AIDS from dirty needles.” He glanced at her with a worried look that she didn’t see. “Is that true, Ivory?”

“Hmm? Oh, AIDS from needles? Well, if you used a dirty needle, maybe. That’s something you shouldn’t have to worry about,” she added firmly, thinking how sad it was that an eight-year-old should know so much of the bad side of life.

He sighed. “Ivory, this is a real bad time to be poor.”

She smoothed a wrinkle in his cap and wished for the hundredth time that she could do more for Tim and his family. After paying the rent and utilities for her own apartment and sending money home to Marlene, there wasn’t a lot left. Even though she was comfortable now, she remembered the hopelessness of being poor, with nothing to look forward to except more deprivation.

“There’s never a good time to be poor, I’m afraid, but, listen, Mrs. Horst down the hall from me gave me a plate full of gingerbread and I brought some today. Would you like a slice of it, and some milk?”

Tim’s face brightened. “Ivory, that would be nice!”

* * *

KELLS-MEREDITH, INCORPORATED WAS on Seventh Avenue in the garment district. It was an old business that Curry Kells, the newest mover and shaker in the New York financial world, had bought out and redesigned. Ivory had never seen him in person, but the senior design staff held him in awe. He didn’t have much to do with the day-to-day working of the company, spending most of his days at his corporate office on Wall Street. He looked in occasionally, to see that everything was in working order; but since Ivory had been working for the company, she hadn’t been around during his rare visits.

She wondered what it would be like to ride around in stretch limousines and eat at the finest hotel restaurants. She had worked hard to improve her speech and her table manners, but she hadn’t had much chance to test her new social graces in high society. Her dreams of becoming an overnight sensation in the New York world of fashion had gone awry from the day she arrived in town, fresh out of design school. Winning first place in the design contest had, indeed, secured her a job as a sketcher-assistant to a designer at Kells-Meredith. It was a far cry from the junior design position she’d hoped for. She knew that years of hard work were required for even the smallest promotion, but she’d dared to hope that she was talented enough to go right to the top.

The big designs, the ones that would be shown in seasonal fashion shows, however, were those of the top in-house designers. Ivory wasn’t permitted to submit designs of her own because the senior designer, Miss Virginia Raines, felt she hadn’t enough experience to think up usable ones. Ivory’s job was to do freehand illustrations of Miss Raines’s designs. She also accessorized outfits for fashion shows—such as the spring showings that had just finished—and made appointments for Miss Raines. Because Ivory was only twenty-two, Miss Raines considered her too young to make contact with buyers and kept that chore for herself. Nor was she receptive to suggestions from Ivory on any designs, despite the fact that nothing new or particularly original ever came from Miss Raines’s mind.

Ivory was walking briskly to work one morning carrying a portfolio of drawings. She had some ideas for the summer line that would be shown in January—if only she could get Miss Raines to take a look at them. Ever the optimist, she was cheerful even if she knew her cause was probably hopeless.

She came to a halt in front of the church half a block from Kells-Meredith. A man sat on the wide stone steps, wrapped up in what appeared to be a fairly expensive gray overcoat. He stared straight ahead at nothing with his one good eye. The other was covered by a black eye patch held in place by a band that cut across his lean, handsome face. He looked like a film star, she thought idly, with his wavy black hair and smooth olive complexion and even features. He had nice hands, too. They were clasped on his lap, the nails very flat, very clean. On the right little finger was a ruby set in a thick, oddly Gothic gold ring. A thin gold watch peeked out from the spotless white cuff over his left wrist. His black shoes had a polish that reflected the sheen of his gray slacks. He was leaning forward, as if in pain, and although people who walked by glanced curiously at him, no one stopped. It was dangerous to stop and help anyone these days. People got killed trying.

Ivory looked at him indecisively, her portfolio of drawings clutched to the front of her buttoned old overcoat. Her jaunty white beret was tilted just a little to the right over her short, wavy golden blond hair. Her gray eyes studied him quietly, intently. She didn’t want to intrude, but he looked as if he needed help.

She approached him slowly, dodging the onrush of people on their way to work, and stopped just in front of him.

He glanced up. His one eye was black as coal, and it glittered with anger and coldness. “What do you want?” he demanded.

The abruptness of the question caught her unawares. She hesitated. “Well...”