Dr. Lavendar's People

"Not for a year, anyway," his wife said, hopefully. "And, besides, I don't think Neddy's thinking of such a thing."

"I hope not, at his age."

"You were engaged when you were nineteen."

"My dear, I wasn't Ned."

Mrs. Dilworth was silent.

"The Packards telegraphed to-day that they wouldn't take that reaper," Tom Dilworth said.

Milly seemed to search for words of sympathy, but before she found them Tom began to talk of something else; he never waited for his wife's replies, or, indeed, expected them. He was so constituted that he had to have a listener; and during all their married life she had listened. When she replied, she was a sounding-board, echoing back his own opinions; when she was silent, he took her silence to mean agreement. Tom used to say that his Milly wasn't one of the smart kind; he didn't like smartness in a woman, anyway; but she had darned good sense; – for, like the rest of us, Thomas Dilworth had a deep belief in the intelligence of the people who agreed with him…

"I have a great mind," he rambled on, "to go up to the Hayeses'. You know that note is due on the 15th, and I believe I'll have to ask him to extend it. I hate to do it, but Packard has upset my calculations, and I'll have to get an extension, or else sell something out; and just now I don't like to do that."

"Very well," she said. It was her birthday – the one day in the year that her Thomas remembered that he had been in love with her for so many years, months, days, hours, minutes – a fact she never for one day in the year forgot. But she could no more have reminded him of the day than she could have flown. She was constitutionally inexpressive.

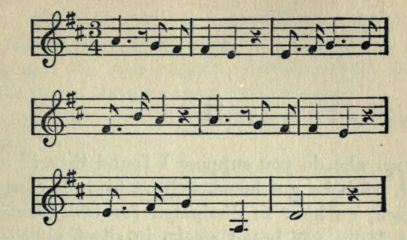

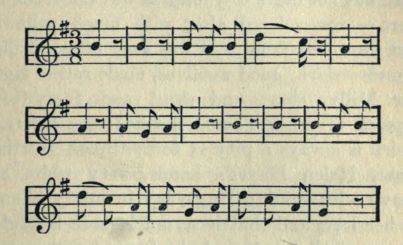

Tom began to whistle:

but broke off to say, "Well, since you advise it, I'll see Hayes"; then he gave her a kiss, and immediately forgot her – as completely as he had forgotten his supper or any other comfortable and absolutely necessary thing. Then he lighted his cigar and started for the Hayeses'.

II"And who do you suppose I found there?" he said, when he got home, well on towards eleven o'clock, an hour so dissipated for Old Chester that Milly was broad awake in silent anxiety. "Why, Ned, if you please! He was talking to Hayes's daughter Helen. She seems a mighty nice girl, Milly. I packed young Edwin off at nine; he was boring Miss Helen to death. Boys have no sense about such things. Can't you give him a hint that women of twenty-five don't care for little boys' talk? By-the-way, she talks mighty well herself. After I settled my business with Hayes, we got to discussing the President's letter; she had just read it."

"Do you mean to say that the President has written to Helen Hayes?" cried Mrs. Dilworth, sitting up in bed in her astonishment.

Thomas roared, and began to pull his boots. "Why, they are regular correspondents! Didn't you know it?"

"No! I hadn't the slightest idea – Tom, you're joking?"

"My dear, you can't think I am capable of joking? But, Milly, look here, I'll tell you one thing: she was mighty sensible about Ned. She thinks there's a good deal to him – "

"I don't need Helen Hayes to tell me that," said Ned's mother.

Tom, who never paused for his wife's reply, was whistling joyfully:

Helen Hayes had been very comforting to him; he had protested, when Ned reluctantly departed, that a boy never knew when to clear out; and Miss Helen had pouted, and said Ned shouldn't be scolded; "I wouldn't let him 'clear out' – so there!" Few women of thirty-two can be cunning successfully, but Tom thought Miss Helen very cunning. "I just perfectly love to hear him talk about his music," she said.

"He can't talk about anything else," Ned's father said. "That's the trouble with him."

"The trouble with him? Why, that's the beauty of him," said Miss Hayes, with enthusiasm; and Thomas said to himself that she was a mighty good-looking girl. The rose-colored lamp-shade cast a soft light on a face that was not quite so young as was the frock she wore – rose-colored also, with much yellowish lace down the front. It was very unlike Milly's dresses – dark, good woollens, made rather tight, for Milly, short and stout and forty-three, aspired (for her Thomas's sake) to a figure, – which is always a pity at forty-three. Furthermore, Helen Hayes's hands, very white and heavy with shining rings, lay in lovely idleness in her lap; and that is so much more restful in a woman's hands than to be fussing with sewing "or everlasting darning," Thomas thought. In fact, what with her lovely idleness and her praise of his boy, Tom Dilworth thought he had rarely seen so pleasing a young woman. "Though she's not so very young, after all; she must be twenty-five," he told his wife.

"She'll never see thirty again."

"Well, she's a mighty nice girl," Thomas said.

Except to look pretty, Miss Helen Hayes had done nothing to produce this impression, for she had contradicted Mr. Dilworth up and down about Ned.

"He has genius, you know."

"You mean his fiddle?" Tom said, incredulously.

"I mean his music. We'll hear of him one of these days."

"I don't care much whether we ever hear from his music," he said, "but I wish I could hear that he was applying himself to business."

"Business!" cried Helen Hayes. "What is business compared to Art?"

Thomas looked over at Mr. Hayes in astonishment, for in those days, in Old Chester, this particular sort of talk had not been heard; the older man sneered and changed his cigar from one corner of his mouth to the other. Miss Hayes did not get much sympathy from her family. But she went on with pretty dogmatism:

"You see, in a man like your son – "

"A man! He's only twenty, my dear young lady."

"In a man, sir! like your son – genius is the thing to consider; and you owe it to the world to let genius have its fullest play. Don't bring Pegasus down to plough Old Chester cornfields. Why, it seems to me," said Helen Hayes, "that he ought to be allowed to just soar. We common folk ought to do the ploughing."

"Thunder an' guns!" said Tom Dilworth.

"I don't care if he can't be sure that two and two make four," cried Miss Helen (Thomas, bubbling into aggrieved confidence on this sore subject, had alleged this against his son); "he can put four notes together that open the gates of heaven. And he'll distinguish himself in music, because his father's son is bound to have tremendous perseverance and energy."

Old Mr. Hayes snorted and spat into the fire; but Miss Helen's look when she said "his father's son" made Mr. Thomas Dilworth simper.

"That girl has sense," he said to himself as he walked home at a quarter to eleven. But he only told Mrs. Dilworth that she had better hint to Ned to be a little more backward in coming forward. "That Hayes girl is nice to him on our account," said Tom, "but he needn't bore her to death. Milly, why don't you have one of those pink wrappers? She had one on to-night. Loose, you know, and trimmed down the front."

"A wrapper isn't very suitable for company," Mrs. Dilworth said, briefly. "It didn't matter with you, because you're an old married man; but she oughtn't to go round in wrappers when Neddy's there."

"Why, it was a sort of party dress – all lace and stuff. I wish you had one like it. As for Ned, he's a babe; and her wrapper thing was perfectly proper, of course. Can't you ask her for the pattern?"

And then Thomas went to sleep and dreamed of a large order for galvanized buckets; but his Milly lay awake a long time, wondering how she could get a pink dress; pleased, in her silent way, that Tom should be thinking about her clothes; but with a slow resentment gathering in her heart that Helen Hayes's clothes should have suggested his thought.

"And pink isn't my color," she thought, a vision of her own mild, red face rising in her mind. Still, a fresh pink lawn – "that's always pretty," Milly Dilworth said to herself, earnestly.

IIITom Dilworth's boy was a curious sport from the family stock. He did, indeed, look down on the hardware business, but not much more than on any business, although galvanized utensils were perhaps a little more hideous than most things. Business in itself did not interest him. Money-making was sordid folly, he said; because, "What do you want money for? Isn't it to buy food and clothes and shelter? Well, you can't eat more food than enough; you can only wear one suit of clothes at a time; and an eight-foot cell is all the shelter that is necessary."

"Eight-foot —grandmother!" his father would retort; "you'll inventory that lot of spades, young man, and dry up."

And Ned, with shrinking hands and ears that shuddered at the hideous screech of scraping shovels, would make out his inventory with loathing. His mother was not impatient or contemptuous with him – she could not have been that to any one; she simply could not understand what he meant when he spouted upon the folly of wealth (for, like most shy people, he occasionally burst into orations upon his theories), or when he set off some fireworks of scepticism borrowed from Mr. Ezra Barkley, or undertook (when Thomas was not present) to prove his father's politics entirely wrong. On such occasions Nancy would say, "Oh, Ned, do be quiet!" and Mary would yawn openly. As for his music, nobody cared about it, except, perhaps, his mother. "But I must say, Neddy, I like a tune," she would say, mildly, after Edwin had tucked his violin under his chin and poured out all his young soul in what was a true and simple passion.

"A tune!" poor Ned said, and groaned. "Mother, I wish you wouldn't call me that ridiculous name."

"I'll try not to, Neddy, dear," she would promise, anxiously; and Ned would groan again.

With such a family circle, one can fancy what it was to the lad when quite by accident he found a friend. It was the summer that he was twenty, that once, coming back in the stage with him from Mercer, Miss Helen Hayes showed a keen interest in something he said; then she asked a question or two; and when, hesitating, waiting for the laugh which did not come, he began to talk, she listened. Oh, the joy of finding a listener! She looked at him, as they sat on the slippery leather seat of the old stage, with soft, intelligent eyes, her slightly faded prettiness giving a touch of charm to the high and flattering gravity of her manner. When she asked him to bring his violin sometime and play to her, the boy could almost have wept with joy. He made haste to work off several of his dearest and most shocking phrases, which she took with deep seriousness: A whale's throat is not large enough to swallow a man – therefore the Biblical account is false, etc., etc. "In fact," said Ned, "if I could have a half-hour's straight conversation with Dr. Lavendar, I could prove to him the falsity of most of the Old Testament."

Helen Hayes was shocked; she regretted Mr. Dilworth's scepticism with almost tearful warmth; yet she realized that a powerful mind must search for truth, above all. She wished, however, that he would read such and such a book. "I can't argue with you myself," she said – "you are far too clever for my poor little reasoning powers."

It was in April that Edwin entered into this experience of feminine sympathy; and by mid-summer, at the time when Mr. Thomas Dilworth also found Miss Helen Hayes so remarkably intelligent, the boy was absorbed in his new emotion of friendship. He never spoke of it at home, hence his father's astonishment at finding him at the Hayeses'. And when, a week later, he found him a second time, Tom Dilworth was much perplexed.

"I dropped in on my way back from the store," he told his wife, "and there was that boy. I said to Miss Helen that she really must not let him bother her. I told her he was a blatherskite, and she must just tell him to dry up if he talked too much."

"Tom, I don't think you ought to talk that way about Neddy," Mrs. Dilworth said. "He's a dear boy."

"He may be a dear boy, but he is a great donkey," Ned's father said, dryly; "and I think it is very good in Helen Hayes to put up with him. I can see she does it on my account. Milly, why don't you ask her to come to supper, sometime? I like to talk to her; she's got brains, that girl. And she's good-looking, too. Ask her to tea, and have waffles and fried chicken, and some of that fluffy pink stuff the children are so fond of, for dessert."

"She's not much of a child," said Mrs. Dilworth, her face growing slowly red. "She's thirty-two if she's a day."

"My dear, she has aged rapidly; you said thirty a month ago. I like the pink stuff myself, and I'm nearly fifty. I bet the Hayeses don't have anything better at their house."

Milly softened at that. Where is the middle-aged housekeeper who does not soften at being told that her pink stuff is better than anything the Hayeses can produce? Yet Tom's talk of Miss Helen's brains pierced through her vagueness and bit into her heart and mind; and she could not forget that he had called the girl good-looking. "Girl!" said Mrs. Dilworth. She was standing before the small swinging glass on her high bureau, looking at herself critically; then she slipped back and locked her door; then took a hand-glass and stood sidewise to look again. Her hair was drawn tightly from her temples and twisted into a hard knot at the back of her head; she remembered that the Hayes girl wore high rats, which were very fashionable, and had a large curl at one side of her waterfall. "But it's pinned on," Milly said to herself; "anyway, mine's my own." Then she pulled her cap farther forward (in those days mothers of families began to wear caps when they were thirty) and looked in the glass again: Helen Hayes did not have a double chin. "She's a skinny thing," Milly said to herself. Yet she knew, bitterly, that she would rather be skinny than see those cruel lines, like gathers on a drawing-string, puckering the once round neck below the chin. And her forehead: she wondered whether if, every day, she stroked it forty-two times, she could smooth out the wrinkles? – those wrinkles that stood for the tender and anxious thought of all her married life! She had heard of getting rid of wrinkles in that way. "It would take a good deal of time," she thought, doubtfully. Still, she might try it – with the door locked. These reflections did not, however, interfere with the invitation which Thomas had suggested.

Milly had her opinion of a middle-aged woman who wore wrappers in public; but if Tom wanted her and her wrappers, he should have them. He should have anything in the world he desired, if she could procure it. Had he desired Miss Hayes hashed on toast, Milly would have done her best to set the dainty dish before her king. And no doubt poor Miss Helen in this form would have given Mrs. Dilworth more personal satisfaction than did her presence at Tom's side (for the invitation was promptly accepted) in some trailing white thing, her eyes fixed on her host's face, intent, apparently, upon any word he might utter. Watching that absorbed and flattering gaze, Milly grew more and more silent. She heard their eager talk, and her mild eyes grew round and full of pain with the sense of being left out; for Miss Hayes, though patient with her hostess, and even kind in a condescending way, hardly spoke to her. Once when, her heart up in her throat, Mrs. Dilworth ventured a comment, it seemed only to amuse Thomas and his guest – and she did not know why.

"This morning," Tom said, "I was h'isting up a big bunch of galvanized buckets to our loft with a fall and tackle, and all of a sudden the strap slipped, and the whole caboodle just whanged down on the pavement – "

"O-o-o-o!" said Helen Hayes, putting her hands over her ears with dramatic girlishness.

"It was terrific, and just at that moment up came Dr. Lavendar. Well, of course I couldn't express my feelings – "

"Poor Mr. Dilworth!"

" – he came up, and gave me a rap with his stick. 'Thomas,' he said (you know how his eyes twinkle!) – 'Thomas, this is the most profane silence I ever heard.'"

Everybody laughed, except Milly and Edwin, the latter remarking that he didn't see anything funny in that. At which Miss Hayes said to him, under her breath, "Oh, you superior people are so contemptuous of our frivolity!" And Ned blushed with satisfaction, and murmured, "Why, no; I'm not superior, I'm sure."

As for Milly, with obvious effort and getting very red, she said that she didn't see how silence could be profane. "As long as you didn't say anything, you conquered your spirit," she added, faintly.

And then they all (except Edwin) laughed again. After that she made no attempt to be taken into the gayety about her, but her heart burned within her. The next morning at breakfast some words struggled out: "You'd think she was a young thing, she laughs so. And she's nearly thirty-five."

"How time flies!" said Tom, chuckling. And then, to everybody's astonishment, the mute Edwin spoke up, and said that as for age it was a matter of the soul and not of the body. "Some people are always young," said Edwin. "Dr. Lavendar is, and you are, father – "

"Thank you, grave and reverend seignior."

" – and mother," continued the candid youth, "has always been old. Haven't you, mother?"

"True, for you, my boy," said the father; "your mother has the wisdom of the family."

Milly Dilworth's face grew dully red to the roots of her hair; a wave of anger rose up in her inarticulate heart. They called her old, these two. She could hardly see her plate for tears.

Edwin, however, was so thrilled by the elegance of his sentiment that he was eager to repeat it to Miss Hayes; but, somehow, he always had difficulty in introducing the subject of age. When he did succeed in getting in his little speech, she said that he impressed her very much when he said things like that. "Your insight is wonderful," she murmured, looking at him with something like awe in her eyes. (Miss Helen was never cunning with Ned.)

"I guess you're the only person that thinks so," Ned said; "at home they're always making fun of me."

"My friend," she said, gravely, "what else can you expect? You are an eagle in a pigeon's nest. I don't mean to criticise your family, but you know as well as I that you are – different. You are an inspiration to me," she ended. And Ned blushed with joy.

It certainly is inspiring to be told you are an inspiration… Mr. Thomas Dilworth did not blush when he learned that mentally he was the most stimulating person that Miss Hayes had ever met; but he had an agreeable consciousness of his superiority, which he made no effort to conceal from his wife. He never made any effort to conceal anything from Milly, not even that fondness for female society which Mrs. Drayton had deplored.

And by-and-by Milly's tears began to lie very near the surface. They never gathered and fell, but perhaps they dropped one by one on her heart, leaving their imprint of patiently accepted pain. At this time she thought of her own mental deficiencies very constantly. Her mind had no flexibility, and she reached conclusions only by toilsome processes; but once reached, they were apt to be permanent. Her slow reasoning at this time led her to conclude that her Thomas was not to blame because he admired some one who was cleverer than she. "Why, he'd be foolish not to," she thought, sadly.

But this eminently reasonable conclusion did not save Mrs. Dilworth from turning white and red with misery, when, for instance, her husband observed that he had had to take down two bars of the Gordon fence, so that Miss Hayes could go home across lots. Then Thomas chuckled, and added that Helen Hayes was the brightest woman he knew.

He did not go on to tell of his walk in the October dusk, and Miss Helen's arch appeal to him for instruction on a certain political point on which she was ignorant. Thomas had instructed her so fully and volubly, while she looked at him with her reverent gaze, that it had grown dark; and that was why he had to take her home across lots. Thomas had not mentioned these details; he merely said he thought Miss Helen Hayes a bright woman – the brightest, to be exact, that he knew. And yet his Milly went into the kitchen pantry and hid her face in the roller behind the door and sobbed.

Well, of course! It's very absurd. A fat, wordless woman, who ought to be darning her children's stockings, it's very absurd for her to be weeping into a roller because her man, who has loved her for forty-three years, eleven months, twenty-nine days, twenty-three hours, and forty minutes – her man, to whom she is as absolutely necessary as his old slippers or his shabby old easy-chair – because this man does not think her the brightest woman he knows. But absurd as it is, it is suffering.

The woman of faithful heart who has been left behind mentally by her husband is a tragic figure, even if she is at the same time a little ridiculous – poor soul! Her futile, panting efforts to catch up; her brave, pitiful blunders; her antics of imitation; her foolish pink lawn frocks – of course they are funny; but the midnight tears are not funny, nor the prinking (behind locked doors), nor the tightened dresses, nor the stealthy reading to "improve the mind" – that poor, anxious, limited mind which knows only its duty to its dearest and best. These things mean the pain – a hopeless pain – of the recognition of limitations. What did it matter that once a year Tom announced that he had loved his Amelia for so many years, months, days, hours, and minutes? – He did not talk to her about the President's letter! But he talked to Helen Hayes about it. And yet she was a pale thing. "She never had my color," poor Milly thought; "and they say she doesn't get along well at home. And she's no housekeeper. Mrs. Hayes herself told me she was just real useless about the house. I can't understand it."

Of course she could not understand it. What feminine mind ever understood why uselessness attracts a sensible man? It is so foolish that even the most foolish woman cannot explain it.

As the autumn closed in on Old Chester, nobody in the family noticed Milly Dilworth's heavier look and deeper silence. Tom himself was more talkative than usual; business had been good, and he was going to get something handsome out of a deal he had gone into with Hayes. This took him often to the Hayeses' house; and after the two men had had their talk, Miss Helen was to be found at the parlor fireside, very arch and eager with questions, but most of all so respectful of Tom's opinions. His Amelia was respectful of his opinions, too, but in such a different way. Perhaps just at this time Thomas Dilworth pitied himself a little – the middle-aged husband does pity himself once in a while. Perhaps he sighed – certainly he whistled. There is no doubt that Mrs. Drayton would have felt he was wandering from his Amelia – at least in imagination. And yet Tom was as settled and grounded in love for his middle-aged wife as he ever had been.

This, however, cannot be understood by those who do not know that the male creature, good and honest and faithful as he may be, is at heart a Mormon.

"I declare," Tom said, coming home at twelve o'clock at night – "I declare I feel younger."

Milly was silent.

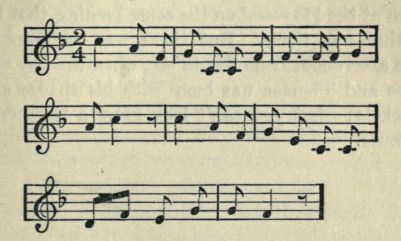

Then Tom began to whistle:

Then he broke off to say that he didn't think that Helen Hayes was over-happy at home. "The Hayeses are commonplace people, and she is very superior. I guess they don't get along well."

Milly thought to herself that when a girl didn't get along with her own mother it didn't speak well for the girl; but she did not say so.

But Thomas went on to declare that he didn't know what to make of Ned. "Hanging round the Hayeses till I'm ashamed of him! Why doesn't he know better? I never bored a woman to death when I was his age." And his wife thought, in heavy silence, that there were other people who hung round the Hayeses.

However, Thomas made his feeling so clear to his son that during the winter Ned was never seen at the Hayeses' on the same evening that his father was there. But there was an hour in the afternoon, from five to six, when the boy was free and Thomas was busy with his spades and buckets; – but you can't look after a boy every minute.