По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

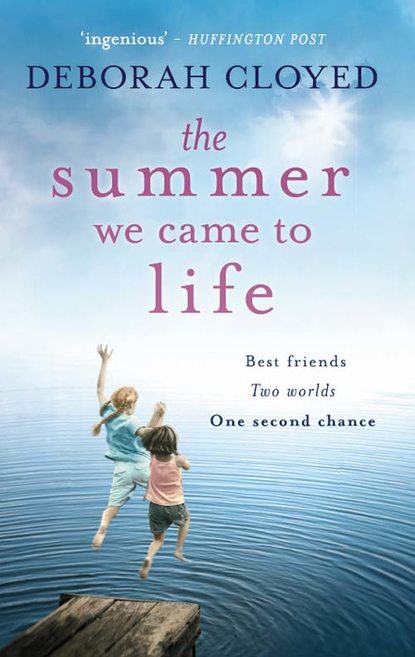

The Summer We Came to Life

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Mina always knew what I was thinking. At that moment, on a rooftop in Paris, without even a glance at my hardening face, she put her hand over mine.

“We are lucky bastards.”

On a cold, hard floor in Tegucigalpa, I looked down at my empty hands lying in my lap, then up at my empty apartment in the middle of nowhere. And then I cried as loud as I wanted. There was nobody to hear.

October 27

Samantha

Our research is not “going nowhere.” We’ll just dig deeper.

The essential problem, Mina, is this:

Nobody knows what consciousness is or exactly how it arises and functions.

Scientists don’t really have a clue what’s happening at a fundamental level of reality. They have fancy equations that explain everything from particle interaction to black holes, but the “how” is linguistically and conceptually challenging, to say the least.

Light really does behave as both a wave and a particle. Matter and energy are interchangeable. Particles really can influence each other at opposite ends of the earth instantaneously. A single electron does somehow go through two holes at once to interfere with itself.

It is the “how” of envisioning such things, and the metaphysical implications, that are disturbing.

Or encouraging.

Mina, this is gonna work. I promise I’ll find you.

Sleep tight.

—Sam.

CHAPTER

3

I WOKE UP THE NEXT MORNING TO THE SOUND of fluttering pages. I wrested my heavy head from the air mattress in pursuit of the source.

Mina’s journal lay open, its pages oscillating. I watched it for a second, mesmerized, then smacked it still and dragged it over.

But then I couldn’t help thumbing through the pages myself, touching Mina’s elegant script and grinning sheepishly at my surplus of graphs and exclamation points. Page after page I read the words I’d read a thousand times. Luv, Sam. Always, Mina. I’ll find you. Promise me.

In the margins were notes I’d added after her death, next to specific tasks we’d planned. I landed on a page from October, where I’d rambled on about Amit Goswami’s Physics of the Soul and consciousness. I’d boldly listed methods of communication Goswami mentioned. The first thing on the list was automatic writing.

I closed the journal.

I lay back on the air mattress and clenched and unclenched my hands at my sides. My mind drifted to a night in my second month in Paris. I watched myself slip out of bed, leaving Remy snoring upon his Egyptian cotton sheets, and walk onto his balcony in the middle of the night. High above the rain-soaked streets, I watched my shaky hand hover over a blank page in the journal, willing every part of my soul to disband or vibrate or do whatever it was supposed to do to connect with Mina’s. I envisioned her—down to the tiny scar on her cheekbone. I conjured her seven different ways of laughing. I replayed our favorite memories. Then I brushed away every sound and image like sweeping a storefront, and waited.

I didn’t even realize I was sobbing until Remy appeared like a ghost on the balcony. When our eyes met, it would be hard to say who was more startled. Without a word, he took off the plush bathrobe he was wearing and wrapped it tight around my shoulders. Then, with a cooing “silly girl,” he took the journal and the pen away, and led me back to bed.

The air mattress protested as I lifted my arms and hugged myself. I had no desire whatsoever to roller-skate that day.

And then my phone rang.

CHAPTER

4

“ET TU, JESSE?” I QUIPPED, HOPING IT WOULD make me sound less like the puddle of misery I was that morning. Isabel’s mother had absolutely no tolerance for misery.

“Samantha, get that tush o’ yours out of bed this instant!” She took a loud slurp of something for emphasis, and I imagined a mocha frappuccino.

“Jesse—”

“Don’t Jesse me, sister, get out your calendar and tell me if you prefer Monday or Tuesday.”

“I don’t get it.”

“We’re comin’, honey. All of us.”

I sat up so fast my butt smacked the floor through the air mattress. “What? Didn’t you talk to Isabel?”

“You bet I did. And Kendra and her mama, too. If ever there was a need for a Honduran vacation, this is it, kiddo.”

“Are you talking about this Monday and Tuesday?”

“Yup and yup.”

“Um, no and no. And I’m done discussing it, so please don’t plan on calling in any more reinforcements.”

“Well,” Jesse said, and slurped, “just so happens I’ve considered your reservations in advance and have called in new reinforcements to address ’em. The boys are comin’, too.”

The journal’s cover flipped open again next to the bed, a breeze shuffling through the first few pages. “What boys?”

“What boys do you think? Cornell and Arshan.”

The thought of Kendra’s and Mina’s fathers joining in on the already unwelcome festivities made my jaw clench in indignation.

“Sorry, Jesse.” I was shaking. “I have to call you back.”

I shut the journal and shoved it under the air mattress.

I paced the stuffy room until I was sure I was suffocating. My phone read noon when I hauled myself out onto the balcony. The city was in full gear, engines chugging along clogged streets, shouts of every emotion fighting to be heard. I looked at my phone. How was I going to fix this? How could I explain? Could I really tell them I don’t fit anymore? You’re not my real family. My life’s a mess. I don’t want you to see me like this. I failed Mina just like I’m failing at everything else.

Halfway to the railing, my foot scraped across something soft and scratchy at the same time. I froze in trepidation. Please don’t be a squished tarantula, please don’t be—

A curling red and yellow maple leaf bolted out from under my toes, so sudden I dropped my phone while bounding after it, just barely rescuing the leaf from a nosedive over the edge.

I pinched the leaf by its stem in between my thumb and forefinger and stared at it as if I’d found a diamond ring in my salad bowl. Not willing to risk the slightest breeze, I held it fast against my chest before leaning forward to peer in every direction around the balcony. Barely any trees at all, and certainly no autumn maple trees like the ones in Virginia outside Mina’s window. I gripped the balcony with one hand to steady myself as I gasped aloud. Then I burst out laughing.

Holding the leaf up to the sun, I wept and laughed simultaneously like a hurricane survivor—juggling hope and grief inside a single human heart. The leaf was a labyrinth of glowing gold and amber veins. The way they were lit up, they looked like crisscrossing canals or waterways. Like the routes of ships. Or airplanes.