По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

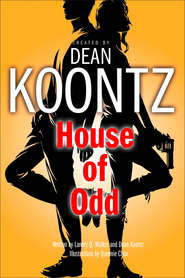

Odd Apocalypse

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Practiced as I am at spirit charades, I figured that she must be indicating the current height of the baby whom she’d once borne, not an infant now but perhaps nine or ten years old. “Not your baby any longer. Your child.”

She nodded vigorously.

“Your child still lives?”

Yes.

“Here in Roseland?”

Yes, yes, yes.

Ablaze in the western sky, those ancient warships built of clouds were burning down from fiery orange to bloody red as the heavens slowly darkened toward purple.

When I asked if her child was a girl or a boy, she indicated the latter.

Although I knew of no children on this estate, I considered the anguish that carved her face, and I asked the most obvious question: “And your son is … what? In trouble here?”

Yes, yes, yes.

Far to the east of the main house in Roseland, out of sight beyond a hurst of live oaks, was a riding ring bristling with weeds. A half-collapsed ranch fence encircled it.

The stables, however, looked as if they had been built last week. Curiously, all the stalls were spotless; not one piece of straw or a single cobweb could be found, no dust, as though the place was thoroughly scrubbed on a regular basis. Judging by that tidiness, and by a smell as crisp and pure as that of a winter day after a snowfall, no horses had been kept there in decades; evidently, the woman in white had been dead a long time.

How, then, could her child be only nine or ten?

Some spirits are exhausted or at least taxed by lengthy contact, and they fade away for hours or days before they renew their power to manifest. This woman seemed to have a strong will that would maintain her apparition. But suddenly, as the air shimmered and a strange sour-yellow light flooded across the land, she and the stallion—which perhaps had been killed in the same event that claimed the life of his mistress—were gone. They didn’t fade or wither from the edges toward the center, as some other displaced souls occasionally did, but vanished in the instant that the light changed.

Precisely when the red dusk became yellow, a wind sprang out of the west, lashing the eucalyptus grove far behind me, rustling through the California live oaks to the south, and blustering my hair into my eyes.

I looked into a sky where the sun had not quite yet gone down, as if some celestial timekeeper had wound the cosmic clock backward a few minutes.

That impossibility was exceeded by another. Yellow from horizon to horizon, without the grace of a single cloud, the heavens were ribboned with what appeared to be high-altitude rivers of smoke or soot. Gray currents streaked through with black. Moving at tremendous velocity. They widened, narrowed, serpentined, sometimes merged, but came apart again.

I had no way of knowing what those rivers were, but the sight strummed a dark chord of intuition. I suspected that high above me raced torrents of ashes, soot, and fine debris that had once been cities, metropolises pulverized by explosions unprecedented in power and number, then vomited high into the atmosphere, caught and held in orbit by the jet stream, by the many jet streams of a war-transformed troposphere.

My waking visions are even rarer than my prophetic dreams. When one afflicts me, I am aware that it’s an internal event, occurring only in my mind. But this spectacle of wind and baleful light and horrific patterns in the sky was no vision. It was as real as a kick in the groin.

Clenched like a fist, my heart pounded, pounded, as across the yellow vault came a flock of creatures like nothing I had seen in flight before. Their true nature was not easily discerned. They were larger than eagles but seemed more like bats, many hundreds of them, incoming from the northwest, descending as they approached. As my heart pounded harder, it seemed that my reason must be knocking to be let out so that the madness of this scene could fully invade me.

Be assured that I am not insane, neither as a serial killer is insane nor in the sense that a man is insane who wears a colander as a hat to prevent the CIA from controlling his mind. I dislike hats of any kind, though I have nothing against colanders properly used.

I have killed more than once, but always in self-defense or to protect the innocent. Such killing cannot be called murder. If you think that it is murder, you’ve led a sheltered life, and I envy you.

Unarmed and greatly outnumbered by the incoming swarm, not sure if they were intent upon destroying me or oblivious of my existence, I had no illusions that self-defense might be possible. I turned and ran down the long slope toward the eucalyptus grove that sheltered the guesthouse where I was staying.

The impossibility of my predicament didn’t inspire the briefest hesitation. Now within two months of my twenty-second birthday, I had been marinated for most of my life in the impossible, and I knew that the true nature of the world was weirder than any bizarre fabric that anyone’s mind might weave from the warp and weft of imagination’s loom.

As I raced eastward, breaking into a sweat as much from fear as from exertion, behind and above me arose the shrill cries of the flock and then the leathery flapping of their wings. Daring to glance back, I saw them rocking through the turbulent wind, their eyes as yellow as the hideous sky. They funneled toward me as though some master to which they answered had promised to work a dark version of the miracle of loaves and fishes, making of me an adequate meal for these multitudes.

When the air shimmered and the yellow light was replaced by red, I stumbled, fell, and rolled onto my back. Raising my hands to ward off the ravenous horde, I found the sky familiar and nothing winging through it except a pair of shore birds in the distance.

I was back in the Roseland where the sun had set, where the sky was largely purple, and where the once-blazing galleons in the air had burned down to sullen red.

Gasping for breath, I got to my feet and watched for a moment as the celestial sea turned black and the last embers of the cloud ships sank into the rising stars.

Although I was not afraid of the night, prudence argued that I would not be wise to linger in it. I continued toward the eucalyptus grove.

The transformed sky and the winged menace, as well as the spirits of the woman and her horse, had given me something to think about. Considering the unusual nature of my life, I need not worry that, when it comes to food for thought, I will ever experience famine.

Two (#ulink_3fd64596-36f3-56bb-821e-42fc5770a6db)

AFTER THE WOMAN, THE HORSE, AND THE YELLOW SKY, I didn’t think I would sleep that night. Lying awake in low lamplight, I found my thoughts following morbid paths.

We are buried when we’re born. The world is a place of graves occupied and graves potential. Life is what happens while we wait for our appointment with the mortician.

Although it is demonstrably true, you are no more likely to see that sentiment on a Starbucks cup than you are the words COFFEE KILLS.

Even before coming to Roseland, I had been in a mood. I was sure I’d cheer up soon. I always do. Regardless of what horror transpires, given a little time, I am as reliably buoyant as a helium balloon.

I don’t know the reason for that buoyancy. Understanding it might be a key part of my life assignment. Perhaps when I realize why I can find humor in the darkest of darknesses, the mortician will call my number and the time will have come to choose my casket.

Actually, I don’t expect to have a casket. The Celestial Office of Life Themes—or whatever it might be called—seems to have decided that my journey through this world will be especially complicated by absurdity and violence of the kind in which the human species takes such pride. Consequently, I’ll probably be torn limb from limb by an angry mob of antiwar protesters and thrown on a bonfire. Or I’ll be struck down by a Rolls-Royce driven by an advocate for the poor.

Certain that I wouldn’t sleep, I slept.

At four o’clock that February morning, I was deep in disturbing dreams of Auschwitz.

My characteristic buoyancy would not occur just yet.

I woke to a familiar cry from beyond the half-open window of my suite in Roseland’s guesthouse. As silvery as the pipes in a Celtic song, the wail sewed threads of sorrow and longing through the night and the woods. It came again, nearer, and then a third time from a distance.

These lamentations were brief, but the previous two days, when they woke me too near dawn, I could not sleep anymore. The cry was like a wire in the blood, conducting a current through every artery and vein. I’d never heard a lonelier sound, and it electrified me with a dread that I could not explain.

In this instance, I awakened from the Nazi death camp. I am not a Jew, but in the nightmare I was Jewish and terrified of dying twice. Dying twice made perfect sense in sleep, but not in the waking world, and the eerie call in the night at once pricked the air out of the vivid dream, which shriveled away from me.

According to the current master of Roseland and everyone who worked for him, the source of the disturbing cry was a loon. They were either ignorant or lying.

I didn’t mean to insult my host and his staff. After all, I am ignorant of many things because I am required to maintain a narrow focus. An ever-increasing number of people seem determined to kill me, so that I need to concentrate on staying alive.

But even in the desert, where I was born and raised, there are ponds and lakes, man-made yet adequate for loons. Their cries were melancholy but never desolate like this, curiously hopeful whereas these were despairing.

Roseland, a private estate, was a mile from the California coast. But loons are loons wherever they nest; they don’t alter their voices to conform to the landscape. They’re birds, not politicians.

Besides, loons aren’t roosters with a timely duty. Yet this wailing came between midnight and dawn, not thus far in sunlight. And it seemed to me that the earlier it came in the new day, the more often it was repeated during the remaining hours of darkness.

I threw back the covers, sat on the edge of the bed, and said, “Spare me that I may serve,” which is a morning prayer that my Granny Sugars taught me to say when I was a little boy.

Pearl Sugars was a professional poker player who frequently sat in private games against card sharks twice her size, guys who didn’t lose with a smile. They didn’t even smile when they won. My grandma was a hard drinker. She ate a boatload of pork fat in various forms. Only when sober, Granny Sugars drove so fast that police in several Southwestern states knew her as Pedal-to-the-Metal Pearl. Yet she lived long and died in her sleep.