По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

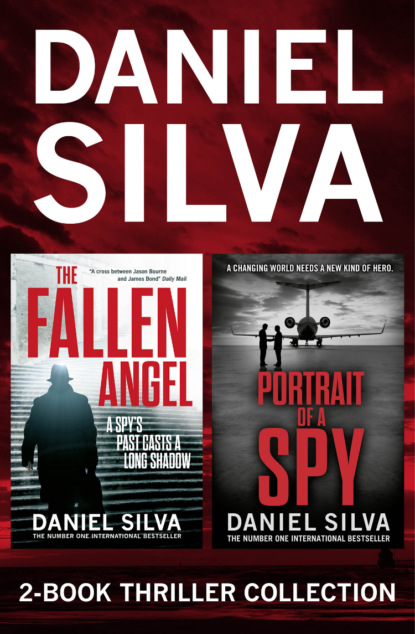

Daniel Silva 2-Book Thriller Collection: Portrait of a Spy, The Fallen Angel

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Because neither Scotland Yard nor the Security Service wanted a rerun of the Menezes fiasco. As a result of his death, a number of new guidelines and procedures were put in place to make sure nothing like it ever happens again. Suffice it to say a single warning does not meet the threshold for taking lethal action—even if the source happens to be named Gabriel Allon.”

“So eighteen innocent people died as a result?”

“What if he wasn’t a terrorist? What if he was another street performer, or someone with mental problems? We would have been burned at the stake.”

“But he wasn’t a street performer or a mental patient, Graham. He was a suicide bomber. And I told you so.”

“How did you know?”

“He might as well have been wearing a sign declaring his intentions.”

“Was it that obvious?”

Gabriel listed the attributes that first raised his suspicions and then explained the calculations that led him to conclude the terrorist intended to detonate his device at 2:37. Seymour shook his head slowly.

“I’ve lost count of how many hours we’ve spent training our police officers to spot potential terrorists, not to mention the millions of pounds we’ve poured into behavior-recognition software for CCTV. And yet a jihadi suicide bomber walked straight into Covent Garden, and no one seemed to notice. No one but you, of course.”

Seymour lapsed into a brooding silence. They were headed north along the floodlit white canyon of Regent Street. Gabriel leaned his head wearily against the window and asked whether the bomber had been identified.

“His name is Farid Khan. His parents immigrated to the United Kingdom from Lahore in the late seventies, but Farid was born in London. Stepney Green, to be precise,” Seymour said. “Like many British Muslims of his generation, he rejected the mild, apolitical religious beliefs of his parents and became an Islamist. By the late nineties, he was spending far too much time at the East London Mosque in Whitechapel Road. Before long, he was a member in good standing of the radical groups Hizb ut-Tahrir and al-Muhajiroun.”

“It sounds to me as if you had a file on him.”

“We did,” Seymour said, “but not for the reasons you might think. You see, Farid Khan was a ray of sunlight, our hope for the future. Or so we thought.”

“You thought you’d turned him around?”

Seymour nodded. “Not long after 9/11, Farid joined a group called New Beginnings. Its goal was to deprogram militants and reintegrate them into the mainstream of Islam and British public opinion. Farid was considered one of their great successes. He shaved his beard. He severed ties to his old friends. He graduated near the top of his class at King’s College and landed a well-paying job with a small London ad agency. A few weeks ago, he became engaged to a woman from his old neighborhood.”

“So you checked him off your list?”

“In a manner of speaking,” Seymour said. “Now it appears it was all a clever deception. Farid was literally a ticking time bomb waiting to explode.”

“Any idea who activated him?”

“We’re poring over his telephone and computer records as we speak, along with the suicide video he left behind. It’s clear his attack was connected to the bombings in Paris and Copenhagen. Whether they were coordinated by the remnants of al-Qaeda Central or a new network is now a matter of intense debate. Whatever the case, it’s none of your concern. Your role in this affair is officially over.”

The Jaguar crossed Cavendish Place and stopped outside the entrance of the Langham Hotel.

“I’d like my gun back.”

“I’ll see what I can do,” Seymour said.

“How long do I have to stay here?”

“Scotland Yard would like you to remain in London for the rest of the weekend. On Monday morning, you can go back to your cottage by the sea and think of nothing other than your Titian.”

“How do you know about the Titian?”

“I know everything. Everything except how to prevent a British-born Muslim from carrying out an act of mass murder in Covent Garden.”

“I could have stopped him, Graham.”

“Yes,” Seymour said distantly. “And we would have repaid the favor by tearing you to pieces.”

Gabriel stepped from the car without another word. “Your role in this affair is officially over,” he murmured as he entered the lobby. He repeated it, again and again, like a mantra.

Chapter 8 New York City (#ulink_f94d41c7-19eb-5b7b-8fb5-1532e68bc7b6)

THAT SAME EVENING, THE OTHER universe inhabited by Gabriel Allon was also on edge but for decidedly different reasons. It was the fall auction season in New York, the anxious time when the art world, in all its folly and excess, convenes for two weeks of frenzied buying and selling. It was, as Nicholas Lovegrove liked to say, one of the few remaining occasions when it was still considered fashionable to be vastly rich. It was also, however, a deadly serious business. Great collections would be built, great fortunes made and lost. A single transaction could launch a brilliant career. It could also destroy one.

Lovegrove’s professional reputation, like Gabriel Allon’s, was by that evening firmly established. British-born and educated, he was regarded as the most sought-after art consultant in the world—a man so powerful he could move markets with an offhand remark or a wrinkle of his elegant nose. His knowledge of art was legendary, as was the size of his bank account. Lovegrove no longer had to troll for clients; they came to him, usually on bended knee and with promises of vast commissions. The secret of Lovegrove’s success lay in his unfailing eye and in his discretion. Lovegrove never betrayed a confidence; Lovegrove never gossiped or engaged in double-dealing. He was the rarest of birds in the art trade—a man of his word.

His reputation notwithstanding, Lovegrove was beset by his usual case of pre-auction jitters as he hurried along Sixth Avenue. After years of falling prices and anemic sales, the art market was at last beginning to show signs of renewal. The season’s first auctions had been respectable but had fallen short of expectations. Tonight’s sale, the Postwar and Contemporary at Christie’s, had the potential to set the art world ablaze. As usual, Lovegrove had clients at both ends of the action. Two were sellers—vendors, in the lexicon of the trade—while a third was looking to acquire Lot 12, Ocher and Red on Red, oil on canvas, by Mark Rothko. The client in question was unique in that Lovegrove did not know his name. He dealt only with a certain Mr. Hamdali in Paris, who in turn dealt with the client. The arrangement was unorthodox but, from Lovegrove’s perspective, highly lucrative. During the past twelve months alone, the collector had acquired more than two hundred million dollars’ worth of paintings. Lovegrove’s commissions on those sales were in excess of twenty million dollars. If things went according to plan tonight, his net worth would rise substantially.

He rounded the corner onto West Forty-ninth Street and walked a half block to the entrance of Christie’s. The soaring glass-walled lobby was a sea of diamonds, silk, ego, and collagen. Lovegrove paused briefly to kiss the perfumed cheek of a German packaging heiress before making his way to the coat check line, where he was promptly set upon by a pair of secondary dealers from the Upper East Side. He put them off with a defensive movement of his hand, then collected his bidding paddle and headed upstairs to the salesroom.

For all its intrigue and glamour, it was a surprisingly ordinary room, a cross between the United Nations General Assembly hall and the church of a television evangelist. The walls were a drab shade of gray-beige, as were the folding chairs, which were smashed tightly together to maximize the limited space. Behind the pulpitlike rostrum was a revolving display case and, next to the case, a bank of telephones staffed by a half-dozen Christie’s employees. Lovegrove glanced up at the sky suites, hoping to glimpse a face or two behind the tinted glass, then turned warily toward the reporters penned like cattle in the back corner. Concealing his paddle number, he hurried past them and headed to his usual seat at the front of the room. It was the Promised Land, the place where all dealers, consultants, and collectors hoped one day to sit. It was not a spot for the faint of heart or the short of cash. Lovegrove referred to it as “the kill zone.”

The auction was scheduled to begin at six. Francis Hunt, Christie’s chief auctioneer, granted his fidgety audience five additional minutes to find their seats before taking his place. He had polished manners and a droll English urbanity that for some inexplicable reason still made Americans feel inferior. In his right hand was the famous “black book” that held the secrets of the universe, at least as far as this evening was concerned. Each lot in the sale had its own page containing information such as the seller’s reserve, a seating chart showing the location of expected bidders, and Hunt’s strategy for extracting the highest possible price. Lovegrove’s name appeared on the page devoted to Lot 12, the Rothko. During a private presale viewing, Lovegrove had hinted he might be interested, but only if the price was right and the stars were in proper alignment. Hunt knew Lovegrove was lying, of course. Hunt knew everything.

He wished the audience a pleasant evening, then, with all the fanfare of a maître d’ summoning a party of four, said, “Lot One, the Twombly.” The bidding commenced immediately, moving swiftly upward in hundred-thousand-dollar increments. The auctioneer deftly managed the process with the help of two immaculately coiffed spotters who strutted and posed behind the rostrum like a pair of male models at a photo shoot. Lovegrove might have been impressed with the performance had he not known it was all carefully choreographed and rehearsed in advance. At one million five, the bidding stalled, only to be revived by a telephone bid for one million six. Five more bids followed in quick succession, at which point the bidding paused for a second time. “The bid is two point one million, with Cordelia on the telephone,” Hunt intoned, eyes moving seductively from bidder to bidder. “It’s not with you, madam. Nor with you, sir. Two point one, on the telephone, for the Twombly. Fair warning now. Last chance.” Down came the gavel with a sharp crack. “Thank you,” murmured Hunt as he recorded the transaction in his black book.

After the Twombly, it was the Lichtenstein, followed by the Basquiat, the Diebenkorn, the De Kooning, the Johns, the Pollock, and a parade of Warhols. Each work fetched more than the presale estimate and more than the previous lot. It was no accident; Hunt had cleverly stacked the deck to create an ascending scale of excitement. By the time Lot 12 slid onto the display case, he had the audience and the bidders exactly where he wanted them.

“On my right we have the Rothko,” he announced. “Shall we start the bidding at twelve million?”

It was two million above the presale estimate, a signal that Hunt expected the work to go big. Lovegrove drew a mobile phone from the breast pocket of his Brioni suit jacket and dialed a number in Paris. Hamdali answered. He had a voice like warm tea sweetened with honey.

“My client would like to get a sense of the room before making a first bid.”

“Wise move.”

Lovegrove placed the phone on his lap and folded his hands. It quickly became apparent they were in for a tough fight. Bids flew at Hunt from all corners of the room and from the Christie’s staff manning the telephones. Hector Candiotti, art adviser to a Belgian industrial magnate, was holding his paddle in the air like a crossing guard, a blusterous bidding technique known as steamrolling. Tony Berringer, who worked for a Russian aluminum oligarch, was bidding as though his life depended on it, which was not beyond the realm of possibility. Lovegrove waited until the price reached thirty million before picking up the phone again.

“Well?” he asked calmly.

“Not yet, Mr. Lovegrove.”

This time, Lovegrove kept the phone pressed to his ear. In Paris, Hamdali was speaking to someone in Arabic. Unfortunately, it was not one of the several languages Lovegrove spoke fluently. Biding his time, he surveyed the sky suites, searching for secret bidders. In one he noticed a beautiful young woman holding a mobile phone. After a few seconds, Lovegrove noticed something else. When Hamdali was speaking, the woman was sitting silently. And when the woman was speaking, Hamdali was saying nothing. It was probably a coincidence, he thought. But then again, maybe not.

“Perhaps it’s time to test the waters,” suggested Lovegrove, his eyes on the woman in the skybox.

“Perhaps you’re right,” answered Hamdali. “One moment, please.”

Hamdali murmured a few words in Arabic. A few seconds later, the woman in the skybox spoke into her mobile phone. Then, in English, Hamdali said, “The client agrees, Mr. Lovegrove. Please make your first bid.”

The current bid was thirty-four million. With the arch of a single eyebrow, Lovegrove raised it by another million.