По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

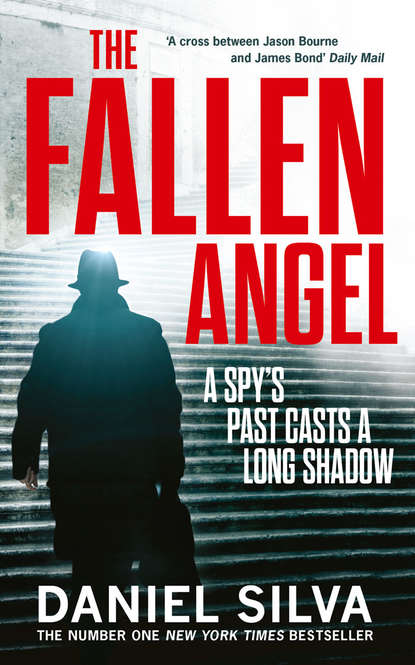

The Fallen Angel

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Italians had imposed two conditions upon the restorer’s return—that he reside in the country under his real name and that he tolerate the presence of occasional physical surveillance. The first he accepted with a certain relief, for after a lifetime on the secret battlefield he was anxious to shed his many aliases and to assume something of a normal life. The second condition, however, had proved more burdensome. The task of following him invariably fell to young trainees. Initially, the restorer had taken mild professional offense until he realized he was being used as the subject of a daily master class in the techniques of street surveillance. He obliged his students by evading them from time to time, always keeping a few of his better moves in reserve lest he find himself in circumstances that required slipping the Italian net.

And so it was that as he made his way through the quiet streets of Rome, he was trailed by no fewer than three probationers of varying skills from the Italian security service. His route presented them with few challenges and no surprises. It bore him westward across the ancient center of the city and terminated, as usual, at St. Anne’s Gate, the business entrance of the Vatican. Because it was technically an international frontier, the watchers had no choice but to entrust the restorer to the care of the Swiss Guard, who admitted him with only a cursory glance at his credentials.

The restorer bade the watchers farewell with a doff of his flat cap and then set out along the Via Belvedere, past the butter-colored Church of St. Anne, the Vatican printing offices, and the headquarters of the Vatican Bank. At the Central Post Office, he turned to the right and crossed a series of courtyards until he came to an unmarked door. Beyond it was a tiny foyer, where a Vatican gendarme sat in a glass box.

“Where’s the usual duty officer?” the restorer asked in rapid Italian.

“Lazio played Milan last night,” the gendarme said with an apathetic shrug.

He ran the restorer’s ID badge through the magnetic card swipe and motioned for him to pass through the metal detector. When the machine emitted a shrill pinging, the restorer stopped in his tracks and nodded wearily at the gendarme’s computer. On the screen, next to the restorer’s unsmiling photograph, was a special notice written by the chief of the Vatican Security Office. The gendarme read it twice to make certain he understood it correctly, then, looking up, found himself staring directly into the restorer’s unusually green eyes. Something about the calmness of his expression—and the hint of a mischievous smile—caused the officer to give an involuntary shiver. He nodded toward the next set of doors and watched intently as the restorer passed through them without a sound.

So, the gendarme thought, the rumors were true. Gabriel Allon, renowned restorer of Old Master paintings, retired Israeli spy and assassin, and savior of the Holy Father, had returned to the Vatican. With a single keystroke, the officer cleared the file from the screen. Then he made the sign of the cross and for the first time in many years recited the act of contrition. It was an odd choice, he thought, because he was guilty of no sin other than curiosity. But surely that was to be forgiven. After all, it wasn’t every day a lowly Vatican policeman had the chance to gaze into the face of a legend.

Fluorescent lights, dimmed to their night settings, hummed softly as Gabriel entered the main conservation lab of the Vatican Picture Gallery. As usual, he was the first to arrive. He closed the door and waited for the reassuring thud of the automatic locks, then made his way along a row of storage cabinets toward the floor-to-ceiling black curtains at the far end of the room. A small sign warned the area beyond the curtains was strictly off-limits. After slipping through the breach, Gabriel went immediately to his trolley and carefully examined the disposition of his supplies. His containers of pigment and medium were precisely as he had left them. So were his Winsor & Newton Series 7 sable brushes, including the one with a telltale spot of azure near the tip that he always left at a precise thirty-degree angle relative to the others. It suggested the cleaning staff had once again resisted the temptation to enter his workspace. He doubted whether his colleagues had shown similar restraint. In fact, he had it on the highest authority that his tiny curtained enclave had displaced the espresso machine in the break room as the most popular gathering spot for museum staff.

He removed his leather jacket and switched on a pair of standing halogen lamps. The Deposition of Christ, widely regarded as Caravaggio’s finest painting, glowed under the intense white light. Gabriel stood motionless before the towering canvas for several minutes, hand pressed to his chin, head tilted to one side, eyes fixed on the haunting image. Nicodemus, muscular and barefoot, stared directly back as he carefully lowered the pale, lifeless body of Christ toward the slab of funerary stone where it would be prepared for entombment. Next to Nicodemus was John the Evangelist, who, in his desperation to touch his beloved teacher one last time, had inadvertently opened the wound in the Savior’s side. Watching silently over them were the Madonna and the Magdalene, their heads bowed, while Mary of Cleophas raised her arms toward the heavens in lamentation. It was a work of both immense sorrow and tenderness, made more striking by Caravaggio’s revolutionary use of light. Even Gabriel, who had been toiling over the painting for weeks, always felt as though he were intruding on a heartbreaking moment of private anguish.

The painting had darkened with age, particularly along the left side of the canvas where the entrance of the tomb had once been clearly visible. There were some in the Italian art establishment—including Giacomo Benedetti, the famed Caravaggisto from the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro—who wondered whether the tomb should be returned to prominence. Benedetti had been forced to share his opinion with a reporter from La Repubblica because the restorer chosen for the project had, for inexplicable reasons, failed to seek his advice before commencing work. What’s more, Benedetti found it disheartening that the museum had refused to make public the restorer’s identity. For many days, the papers had bristled with familiar calls for the Vatican to lift the veil of silence. How was it possible, they fumed, that a national treasure like The Deposition could be entrusted to a man with no name? The tempest, such as it was, finally ended when Antonio Calvesi, the Vatican’s chief conservator, acknowledged that the man in question had impeccable credentials, including two masterful restorations for the Holy See—Reni’s Crucifixion of St. Peter and Poussin’s Martyrdom of St. Erasmus. Calvesi neglected to mention that both projects, conducted at a remote Umbrian villa, had been delayed due to operations the restorer had carried out for the secret intelligence service of the State of Israel.

Gabriel had hoped to restore the Caravaggio in seclusion as well, but Calvesi’s decree that the painting never leave the Vatican had left him with no choice but to work inside the lab, surrounded by the permanent staff. He was the subject of intense curiosity, but then, that was to be expected. For many years, they had believed him to be an unusually gifted if temperamental restorer named Mario Delvecchio, only to learn that he was something quite different. But if they felt betrayed, they gave no sign of it. Indeed, for the most part, they treated him with a tenderness that came naturally to those who care for damaged objects. They were quiet in his presence, mindful to a point of his obvious need for privacy, and were careful not to look too long into his eyes, as if they feared what they might find there. On those rare occasions when they addressed him, their remarks were limited mainly to pleasantries and art. And when office banter turned to the politics of the Middle East, they respectfully muted their criticism of the country of his birth. Only Enrico Bacci, who had lobbied intensely for the Caravaggio restoration, objected to Gabriel’s presence on moral grounds. He referred to the black curtain as “the Separation Fence” and adhered a “Free Palestine” poster to the wall of his tiny office.

Gabriel poured a tiny pool of Mowolith 20 medium onto his palette, added a few granules of dry pigment, and thinned the mixture with Arcosolve until it reached the desired consistency and intensity. Then he slipped on a magnifying visor and focused his gaze on the right hand of Christ. It hung in the manner of Michelangelo’s Pietà, with the fingers pointing allegorically toward the corner of the funerary stone. For several days, Gabriel had been attempting to repair a series of abrasions along the knuckles. He was not the first artist to struggle over the composition; Caravaggio himself had painted five other versions before finally completing the painting in 1604. Unlike his previous commission—a depiction of the Virgin’s death so controversial it was eventually removed from the church of Santa Maria della Scala—The Deposition was instantly hailed as a masterwork, and its reputation quickly spread throughout Europe. In 1797, the painting caught the eye of Napoléon Bonaparte, one of history’s greatest looters of art and antiquities, and it was carted over the Alps to Paris. It remained there until 1817, when it was returned to the custody of the papacy and hung in the Vatican.

For several hours, Gabriel had the lab to himself. Then, at the thoroughly Roman hour of ten, he heard the snap of the automatic locks, followed by Enrico Bacci’s lumbering plod. Next came Donatella Ricci, an Early Renaissance expert who whispered soothingly to the paintings in her care. After that it was Tommaso Antonelli, one of the stars of the Sistine Chapel restoration, who always tiptoed around the lab in his crepe-soled shoes with the stealth of a night thief.

Finally, at half past ten, Gabriel heard the distinctive tap of Antonio Calvesi’s handmade shoes over the linoleum floor. A few seconds later, Calvesi came whirling through the black curtain like a matador. With his disheveled forelock and perpetually loosened necktie, he had the air of a man who was running late for an appointment he would rather not keep. He settled himself atop a tall stool and nibbled thoughtfully at the stem of his reading glasses while inspecting Gabriel’s work.

“Not bad,” Calvesi said with genuine admiration. “Did you do that on your own, or did Caravaggio drop by to handle the in-painting himself?”

“I asked for his help,” Gabriel replied, “but he was unavailable.”

“Really? Where was he?”

“Back in prison at Tor di Nona. Apparently, he was roaming the Campo Marzio with a sword.”

“Again?” Calvesi leaned closer to the canvas. “If I were you, I’d consider replacing those lines of craquelure along the index finger.”

Gabriel raised his magnifying visor and offered Calvesi the palette. The Italian responded with a conciliatory smile. He was a gifted restorer in his own right—indeed, in their youth, the two men had been rivals—but it had been many years since he had actually applied a brush to canvas. These days, Calvesi spent most of his time pursuing money. For all its earthly riches, the Vatican was forced to rely on the kindness of strangers to care for its extraordinary collection of art and antiquities. Gabriel’s paltry stipend was a fraction of what he earned for a private restoration. It was, however, a small price to pay for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to clean a painting like The Deposition.

“Any chance you might actually finish it sometime soon?” Calvesi asked. “I’d like to have it back in the gallery for Holy Week.”

“When does it fall this year?”

“I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that.” Calvesi picked absently through the contents of Gabriel’s trolley.

“Something on your mind, Antonio?”

“One of our most important patrons is dropping by the museum tomorrow. An American. Very deep pockets. The kind of pockets that keep this place functioning.”

“And?”

“He’s asked to see the Caravaggio. In fact, he was wondering whether someone might be willing to give him a brief lecture on the restoration.”

“Have you been sniffing the acetone again, Antonio?”

“Won’t you at least let him see it?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

Gabriel gazed at the painting for a moment in silence. “Because it wouldn’t be fair to him,” he said finally.

“The patron?”

“Caravaggio. Restoration is supposed to be our little secret, Antonio. Our job is to come and go without being seen. And it should be done in private.”

“What if I get Caravaggio’s permission?”

“Just don’t ask him while he has a sword in his hand.” Gabriel lowered the magnifying visor and resumed his work.

“You know, Gabriel, you’re just like him. Stubborn, conceited, and far too talented for your own good.”

“Is there anything else I can do for you, Antonio?” asked Gabriel, tapping his brush impatiently against his palette.

“Not me,” Calvesi replied, “but you’re wanted in the chapel.”

“Which chapel?”

“The only one that matters.” Gabriel wiped his brush and placed it carefully on the trolley. Calvesi smiled.

“You share one other trait with your friend Caravaggio.”

“What’s that?”

“Paranoia.”

“Caravaggio had good reason to be paranoid. And so do I.”

3

THE SISTINE CHAPEL

THE 5,896 SQUARE FEET OF the Sistine Chapel are perhaps the most visited piece of real estate in Rome. Each day, several thousand tourists pour through its rather ordinary doors to crane their necks in wonder at the glorious frescoes that adorn its walls and ceiling, watched over by blue-uniformed gendarmes who seem to have no other job than to constantly plead for silenzio. To stand alone in the chapel, however, is to experience it as its namesake Pope Sixtus IV had intended. With the lights dimmed and the crowds absent, it is almost possible to hear the quarrels of conclaves past or to see Michelangelo atop his scaffolding putting the finishing touches on The Creation of Adam.

On the western wall of the chapel is Michelangelo’s other Sistine masterwork, The Last Judgment. Begun thirty years after the ceiling was completed, it depicts the Apocalypse and the Second Coming of Christ, with all the souls of humanity rising or falling to meet their eternal reward or punishment in a swirl of color and anguish. The fresco is the first thing the cardinals see when they enter the chapel to choose a new pope, and on that morning it seemed the primary preoccupation of a single priest. Tall, lean, and strikingly handsome, he was cloaked in a black cassock with a magenta-colored sash and piping, handmade by an ecclesiastical tailor near the Pantheon. His dark eyes radiated a fierce and uncompromising intelligence, while the set of his jaw indicated he was a dangerous man to cross, which had the added benefit of being the truth. Monsignor Luigi Donati, private secretary to His Holiness Pope Paul VII, had few friends behind the walls of the Vatican, only occasional allies and sworn rivals. They often referred to him as a clerical Rasputin, the true power behind the papal throne, or “the Black Pope,” an unflattering reference to his Jesuit past. Donati didn’t mind. Though he was a devoted student of Ignatius and Augustine, he tended to rely more on the guidance of a secular Italian philosopher named Machiavelli, who counseled that it is far better for a prince to be feared than loved.

Among Donati’s many transgressions, at least in the eyes of some members of the Vatican’s gossipy papal court, were his unusually close ties to the notorious spy and assassin Gabriel Allon. Theirs was a partnership that defied history and faith—Donati, the soldier of Christ, and Gabriel, the man of art who by accident of birth had been compelled to lead a clandestine life of violence. Despite those obvious differences, they had much in common. Both were men of high morals and principle, and both believed that matters of consequence were best handled in private. During their long friendship, Gabriel had acted as both the Vatican’s protector and a revealer of some of its darkest secrets—and Donati, the Holy Father’s hard man in black, had served as his willing accomplice. As a result, the two men had done much to quietly improve the tortured relationship between the world’s Catholics and their twelve million distant spiritual cousins, the Jews.