По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

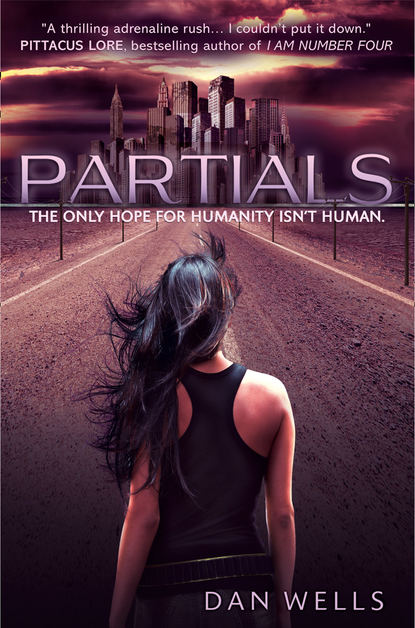

Partials

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

PART 3 - FOUR HOURS LATER

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_0e74806b-7a62-53a0-a21d-f7555cd0fe93)

(#ulink_1d7f1e5d-55f1-55d2-bb03-5c14be9f8a91)

Newborn #485GA18M died on June 30, 2076, at 6:07 in the morning. She was three days old. The average lifespan of a human child, in the time since the Break, was fifty-six hours.

They didn’t even name them anymore.

Kira Walker looked on helplessly while Dr. Skousen examined the tiny body. The nurses—half of them pregnant as well—recorded the details of its life and death, faceless in bodysuits and gas masks. The mother wailed despondently from the hallway, muffled by the glass. Ariel McAdams, barely eighteen years old. The mother of a corpse.

“Core temperature ninety-nine degrees at birth,” said a nurse, scrolling through the thermometer readout. Her voice was tinny through the mask; Kira didn’t know her name. Another nurse carefully transcribed the numbers on a sheet of yellow paper. “Ninety-eight degrees at two days,” the nurse continued. “Ninety-nine at four o’clock this morning. One-oh-nine point five at time of death.” They moved softly through the room, pale green shadows in a land of the dead.

“Just let me hold her,” cried Ariel. Her voice cracked and broke. “Just let me hold her.”

The nurses ignored her. This was the third birth this week, and the third death; it was more important to record the death, to learn from it—to prevent, if not the next one, then the one after that, or the hundredth, or the thousandth. To find a way, somehow, to help a human child survive.

“Heart rate?” asked another nurse.

I can’t do this anymore, thought Kira. I’m here to be a nurse, not an undertaker—

“Heart rate?” asked the nurse again, her voice insistent. It was Nurse Hardy, the head of maternity.

Kira snapped back to attention; monitoring the heart was her job. “Heart rate steady until four this morning, spiking from 107 to 133 beats per minute. Heart rate at five o’clock was 149. Heart rate at six was 154. Heart rate at six-oh-six was . . . 72.”

Ariel wailed again.

“My figures confirm,” said another nurse. Nurse Hardy wrote the numbers down but scowled at Kira.

“You need to stay focused,” she said gruffly. “There are a lot of medical interns who would give their right eye for your spot here.”

Kira nodded. “Yes, ma’am.”

In the center of the room Dr. Skousen stood, handed the dead infant to a nurse, and pulled off his gas mask. His eyes looked as dead as the child. “I think that’s all we can learn for now. Get this cleaned up, and prepare full blood work.” He walked out, and all around Kira the nurses continued their flurry of action, wrapping the baby for burial, scrubbing down the equipment, sopping up the blood. The mother cried, forgotten and alone—Ariel had been inseminated artificially, and there was no husband or boyfriend to comfort her. Kira obediently gathered the records for storage and analysis, but she couldn’t stop looking at the sobbing girl beyond the glass.

“Keep your head in the game, intern,” said Nurse Hardy. She pulled off her mask as well, her hair plastered with sweat to her forehead. Kira looked at her mutely. Nurse Hardy stared back, then raised her eyebrow. “What does the spike in temperature tell us?”

“That the virus tipped over the saturation point,” said Kira, reciting from memory. “It replicated itself enough to overwhelm her respiratory system, and the heart started overreaching to try to compensate.”

Nurse Hardy nodded, and Kira noticed for the first time that her eyes were raw and bloodshot. “One of these days the researchers will find a pattern in this data and use it to synthesize a cure. The only way they’re going to do that is if we . . . ?” She paused, waiting, and Kira filled in the rest.

“Track the course of the disease through every child the best we can, and learn from our mistakes.”

“Finding a cure is going to depend on the data in your hands.” Nurse Hardy pointed at Kira’s papers. “Fail to record it, and this child died for nothing.”

Kira nodded again, numbly straightening the papers in her manila folder.

The head nurse turned away, but Kira tapped her on the shoulder; when she turned back, Kira didn’t dare to look her in the eye. “Excuse me, ma’am, but if the doctor’s done with the body, could Ariel hold it? Just for a minute?”

Nurse Hardy sighed, weariness cracking through her grim, professional facade. “Look, Kira,” she said. “I know how quickly you breezed through the training program. You clearly have an aptitude for virology and RM analysis, but technical skills are only half the job. You need to be ready, emotionally, or the maternity ward will eat you alive. You’ve been with us for three weeks—this is your tenth dead child. It’s my nine hundred eighty-second.” She paused, her silence dragging on longer than Kira expected. “You’ve just got to learn to move on.”

Kira looked toward Ariel, crying and beating on the thick glass window. “I know you’ve lost a lot of them, ma’am.” Kira swallowed. “But this is Ariel’s first.”

Nurse Hardy stared at Kira for a long time, a distant shadow in her eyes. Finally she turned. “Sandy?”

Another young nurse, who was carrying the tiny body to the door, looked up.

“Unwrap the baby,” said Nurse Hardy. “Her mother is going to hold her.”

Kira finished her paperwork about an hour later, just in time for the town hall meeting with the Senate. Marcus met her in the lobby with a kiss, and she tried to put the long night’s tension behind her. Marcus smiled, and she smiled back weakly. Life was always easier with him around.

They left the hospital, and Kira blinked at the sudden burst of natural sunlight on her exhausted eyes. The hospital was like a bastion of technology in the center of the city, so different from the ruined houses and overgrown streets it may as well have been a spaceship. The worst of the mess had been cleaned up, of course, but the signs of the Break were still everywhere, even eleven years later: abandoned cars had become stands for fish and vegetables; front lawns had become gardens and chicken runs. A world that had been so civilized—the old world, the world from before the Break—was now a borrowed ruin for a culture one step up from the Stone Age. The solar panels that powered the hospital were a luxury most of East Meadow could only dream of.

Kira kicked a rock in the road. “I don’t think I can do this anymore.”

“You want a rickshaw?” asked Marcus. “The coliseum’s not that far.”