По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

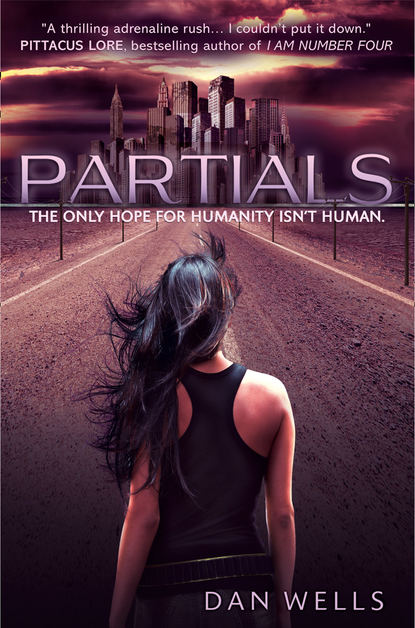

Partials

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“We don’t get certain minerals in our diets here,” Kira whispered. “Pregnant cravings are your body’s way of telling you what nutrients it needs. Dirt’s not that uncommon with our diet.”

“I’m going to go into the hospital in a few days to get tested for real,” said Madison, “but I wanted to tell you first.”

“No,” said Kira again, shaking her head. This couldn’t be happening—she knew that it could, that it was in fact very likely, but at the same time she knew that no, this was Madison, this was the closest thing to a sister, to a family, that Kira had left. “Do you have any idea what it’s like?” she asked. “The pain? The danger? Women die in childbirth; even with all our equipment and experience at the hospital it still happens, and then even if you live, your baby won’t. We haven’t cured RM yet—you’re going to live with this for a few more months, and go through all that pain and terror and blood and everything else, and then it’s going to die.” Kira felt herself tearing up, felt a hot wetness welling up in her eyes and spilling coldly down her face. She imagined Madison where Ariel had been, wide-eyed and screaming, banging on the glass as her daughter squirmed and wailed and died. “Haru is right to be upset,” she said, wiping her face with her fingers. “This is too much for you, you don’t need this.”

“Yes, I do,” said Madison softly.

“It’s a stupid law,” said Kira, raising her voice angrily before glancing nervously toward the hallway and lowering it again. “You don’t have to go through with this. Give me more time—fake sterility or something, it happens, just don’t—”

“It’s already done,” said Madison. Her smile was the sweet, beatific smile Kira had seen on a dozen other mothers, and it broke her heart. Madison put her hand on Kira’s. “I didn’t do this for the Hope Act, and I didn’t do this for the Senate, I did it for me.”

Kira shook her head, tears still rolling down her face.

“I want this,” said Madison. “I was born to be a mother—it’s in my genes, it’s right here in the center of who I am.” She clutched at her chest and blinked back a few tears of her own. “I know that it scares you, and I know it scares Haru. It scares me too, it scares me to death, but it’s the right thing to do. Even if it only lasts for a few days—even if it only lasts for a few hours.”

“Oh, Madison.” Kira leaned forward, clasping her friend in an embrace. She felt terrified and guilty, knowing she was right but ashamed of herself for dumping on Madison like that. Of course Madison knew the risks; everyone on the island knew them. Madison wasn’t running away from them, she was meeting them head-on.

Kira pulled back, wiping her eyes again.

“One of these days we will have a survivor,” she said. “It’s inevitable. A child will live. It might be yours.”

Marcus walked in with a broad wooden tray and stopped at the sight of them hugging and crying. “Is everything okay?”

“I’ll tell you later,” said Kira, pulling back from Madison and wiping her eyes again. Her cheeks felt raw from the constant scrubbing.

“Okay,” he said slowly, setting the tray on the low central table. Xochi had covered it with a whole roast chicken, crusted with herbs and dripping with juices, and a heaping pile of pan-fried potatoes. Xochi followed next with a tray of vegetables—all fresh in honor of the holiday—and Nandita came last with a tray of chocolate-covered doughnuts. Kira’s mouth watered; she couldn’t remember the last time she’d had anything so good. It might have been a full year ago on the last Rebuilding Day.

Marcus stooped in front of Kira. “Do you need anything? Can I get you a drink or whatever?”

Kira shook her head. “I’m fine, but could you get Mads some water?”

“I’ll get some for you, too.” He slid his hand gently across her shoulder, then walked back to the kitchen.

Xochi looked at Madison, then at Kira. She said nothing, but turned to the stereo. “I think we need something a little more laid-back.” The music hub was a small panel on a shelf along the wall, connected wirelessly to a series of speakers around the room. The center of the panel held a small dock for a digital music player, which Xochi unplugged and dropped into a basket. “Any requests?”

Madison smiled. “Laid-back sounds nice.”

“Use Athena,” said Kira, standing up to help. “I always like Athena.” She and Xochi sifted through the basket—a wide wicker thing filled with slim silver bricks. Most of them were monogrammed: TO CATELYN, FROM DADDY. TO CHRISTOPH: HAPPY BIRTHDAY. Even the ones without monograms bore some kind of identifying mark: a plastic cover with a picture or pattern; an image etched into the back; a small charm dangling from the corner. They were more than receptacles for music, they were records of a personality—an actual person, their likes and dislikes, their tastes and inner thoughts reflected in their playlists. Xochi had spent years scavenging the players from the rubble, and she and Kira would lie on the floor for hours on end, listening to each player and imagining what its owner must have been like. TO KATHERINE ON HER GRADUATION was full of country music, cheerful and twangy and wearing its heart on its sleeve. JIMMY OLSEN listened to everything, from ancient chants to orchestral symphonies to thrashing rock and metal. Kira found her favorite almost at the bottom, ATHENA, MY ANGEL, and plugged it into the dock. A few seconds later the first song started, soft and driving at once, a subtle wall of electronic waves and dissonant guitars and intimate, throaty vocals. It was calming and comfortable and sad all at once, and it fit Kira’s mood perfectly. She closed her eyes and smiled. “I think I would have liked Athena. Whoever she was.”

Marcus returned with the water, and a moment later Haru came in from the back porch. His face was solemn, but he seemed calmer, and he nodded politely to Xochi. “This smells delicious. Thank you for making it.”

“My pleasure.”

Kira glanced quickly around. “Are we waiting for anyone?”

Madison shook her head. “I tried to talk to Ariel, but she’s still not talking to me. And Isolde’s going to be late, and said to start without her—there’s something big at the Senate, and Hobb’s keeping her longer.”

“Lucky girl,” said Xochi. She passed out plates and forks, and they paused before digging into the food.

“Happy Rebuilding Day,” said Marcus. He raised his glass of water, and the others did the same; the glasses were perfectly matched, crystal goblets salvaged from a huge estate outside of town, and the water inside was boiled and fresh, tinged slightly yellow from the chemicals in Nandita’s purifier.

“The old world ended,” said Madison, intoning the familiar words, “but the new one is only beginning.”

“We will never forget the past,” said Haru, “and we will never forsake the future.”

Xochi raised her chin, holding her head high. “Life comes from death, and weakness teaches us strength.”

“Nothing can defeat us,” said Kira. “We can do anything.” She paused, then added softly, “We will do everything.”

They drank, and for a moment all was silent but the music, soft and haunting in the background. Kira swallowed the water in slow gulps, sloshing it thoughtfully in her mouth, tasting the chemical tang. She rarely even noticed it anymore, but it was there, sharp and bitter. She thought about Madison and Haru, and about their baby, perfect and innocent and doomed. She thought about Gianna, and Mkele, and the explosion and the Voice and the Senate and everything else, the entire world, the future and the past. I’m not going to let it die, she thought, and looked at Madison’s belly, still firm and flat and unchanged. I’m going to save you, no matter what it takes.

We will do everything.

(#ulink_efa4ce01-8819-5b6d-b37f-4ddf6c5653b9)

“I need a sample of your blood,” said Kira.

Marcus raised an eyebrow. “I didn’t know we’d reached that stage of our relationship.”

She ripped up a tuft of grass and threw it at him. “It’s for work, genius.” They were on Kira’s front lawn, enjoying a rare instance when they both had the same day off. They’d helped Nandita with the herb garden for a few hours, and their hands were rough and fragrant. “I’m going to cure RM.”

Marcus laughed. “I wondered when someone would finally get around to that. It’s been on my to-do list for ages, but you know how things are: Life gets so busy, and saving the human race is such an inconvenience—”

“I’m serious,” said Kira. “I can’t just watch children die anymore. I can’t just stand there and take notes while Madison’s baby dies. I’m not going to do it. It’s been weeks since she told us, and I’ve been racking my brain for anything I can do to help, and I think I finally have a workable starting point.”

“All right, then,” said Marcus, sitting up in the grass. His face was more serious now. “You know that I think you’re brilliant, and you got better grades in virology than . . . anyone. Ever. How do you expect to suddenly solve the biggest medical mystery in history? I mean, there’s an entire research team at the hospital that’s been trying to figure out RM for a decade, and now a medical intern is going to step in and just . . . cure it? Just like that?”

Kira nodded; it really did sound stupid when he said it like that. She glanced over at Nandita, wondering what her opinion would be on the matter, but the old woman was still working in the garden, completely unaware. Kira turned back to Marcus. “I know it sounds like the most arrogant thing in the whole world, but I—” She paused and took a breath, looking him squarely in the eyes. He was watching, waiting; he was taking her seriously. She put her hand on his. “I know I can help, at the very least. There has to be something that’s been overlooked. I joined maternity because I thought that was the nerve center, you know? I thought that was the whole point, the place where it all happened. But now that I’ve been there and I’ve seen what they’re doing, I know it’s not going to work.

“If I can put together something concrete for Skousen, I bet I can transfer to research full-time—it’ll take another month or two, but I can do it.”

“That’s a good move for you,” said Marcus. “It’ll be good for them, too—coming from maternity like that, you’ll have a different perspective from the others. And I know there’s an opening, because we got a transfer from research into surgery last month.”

“That’s exactly what I mean,” said Kira, “a new perspective. The maternity team, the research team, everybody’s been studying the infants exclusively. But we don’t need to look for a cure, we need to look for immunity. We’re resistant to the symptoms, so there has to be something in us that fends off the virus. The only ones who aren’t immune are the babies, and yet that’s where we keep looking.”

“That’s why you need my blood,” said Marcus.

Kira nodded, rubbing her fingers over the back of his hand. That was why she loved Marcus: He was funny when she needed to laugh, and serious when she needed to talk. He understood her, plain and simple.

She plucked a blade of grass and slowly peeled it until nothing remained but the soft yellow core. She studied it a moment, then threw it at Marcus; it traveled only a few inches before it caught the air, stopped, and fluttered in erratic circles straight back into her lap.

“Nice shot,” grinned Marcus. He looked up over her shoulder. “Isolde’s coming.”

Kira turned and smiled, waving at her “sister.” Isolde was tall and pale and golden-haired—the lone light-skinned outlier in Nandita’s makeshift foster home. Isolde waved back, grinning, though Kira could see that the smile was forced and tired. Marcus scooted over as she approached, making room beside them on the grass, but Isolde shook her head politely.

“Thanks, but this is my best suit.” She dropped her briefcase and stood next to them wearily, arms folded, staring straight ahead.

“Rough day in the Senate?” Kira asked.