По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

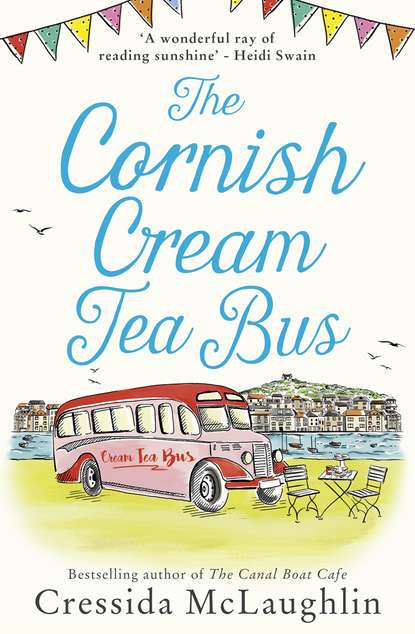

The Cornish Cream Tea Bus

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘And I can’t wait to see what the locals think of the bus.’ Daniel’s eyes shone. ‘They’re quite protective of their way of life. You’ll find that out sooner rather than later.’

‘Oh, I think I already have. Thanks for the lesson.’ She smiled sweetly.

Daniel shook his head and sighed. He tugged on the German shepherd’s lead just as Marmite inched forwards, his fear fading. ‘Nice to meet you, Charlie. Lawrence, Juliette.’ He nodded a brief goodbye and led his dog away.

‘See what I mean?’ Juliette said, once the door had closed behind Daniel. ‘He is selfish, obsessed with that hotel and completely uncaring.’ She folded her arms, and Lawrence reached over and squeezed her hand.

Charlie sipped her drink. Her friend was so mild-mannered and always saw the good in people, so for her to be so vehemently against Daniel was unusual. He certainly hadn’t endeared himself to Charlie, but he hadn’t come across as a monster, either. He was obviously passionate about his hotel, and confident to the point of arrogance, but she had seen amusement and intelligence in his eyes, and couldn’t believe he was entirely thoughtless. She was sure there was something more personal to Juliette’s dislike of him – something that she was reluctant to share. She wondered how she could tease the answer out of her.

‘So, back to Gertie,’ Juliette said, topping up their glasses. ‘When do we start work on her?’

It was a week later and Gertie was gone from the car park.

Charlie walked down the hill with Marmite, the sun almost absent today, just a weak pulse behind rolling clouds as if it was trying to push open a heavy door. She glanced up at Crystal Waters, and wondered if Daniel had thrown himself a party when she’d driven Gertie out of Porthgolow. Then again, from what little she’d seen, he didn’t seem like the partying kind. He’d more likely poured himself a large whisky in his walnut-panelled office and thrown fish chum to the sharks swimming in the glass tank underneath the floor. Charlie shook her head to clear the image; she’d been watching too many Bond films with Lawrence and Juliette.

But Gertie wasn’t gone because of what Daniel had said in the pub, or because he’d subsequently pulled strings with some Cornwall government cronies. Gertie was gone because Lawrence’s friend, Pete, who ran a surfing supplies shop in Newquay and refurbished camper vans in his spare time, had taken on Charlie’s project with gusto. He had listened to her and Juliette’s ideas in a hipster café overlooking Newquay sands while they drank coffee out of Kilner jars, and turned around the plans within a couple of days.

His realization of her ideas was amazing, and Charlie had been in a perpetual state of excitement ever since, picturing the tables with cup-holders built in, so that Charlie could drive the bus with customers on it but without fear of spillage; the scarlet and royal-blue seat covers, the kitchen area downstairs complete with sink, fridge and compact oven; a built-in coffee machine that would have no chance of slipping off the counter. The plans were as breathtaking as the price of the renovations, but once Charlie had heard them, she couldn’t imagine anything less for Gertie.

The sale of the flat had gone through, and she’d been able to put down the deposit for the work. Now Gertie had gone to stay in Pete’s workshop for the next month, to be gutted and rebuilt, with the necessary water tanks and generators, everything plumbed in, fixed and decorated. Charlie was looking forward to the final result with a heady mix of excitement and extreme nerves. At the same time she had been applying for her food handlers permit and her trading consent. Her food hygiene was up to date from working in The Café on the Hill, and even though she had concerns – mainly from the reactions of some of the locals – that she wouldn’t be welcome in Porthgolow, Cornwall Council seemed happy for her to have a pitch on the hard-packed sand at the top of the beach. Charlie couldn’t help but wonder if that was because, even in their eyes, the village needed livening up.

She pushed open the door of the Porthgolow Pop-In, the general store which, beyond the milk, bread and newspapers, was a treasure trove of weird and wonderful objects. Myrtle Gordon looked up from the Jackie Collins paperback she was reading, her glasses low on her nose.

‘Hi Myrtle,’ Charlie called tentatively.

‘Your dog, ’ees not peeing on my paintwork, is ’ee?’ she called. ‘If ’ee is, you can pay for it.’

Charlie felt herself blush. ‘He won’t, he’s just been— he’ll be fine.’

‘Good to know,’ Myrtle replied coldly, and went back to her book.

Charlie walked down the narrow aisles, marvelling at the Matchbox tin cars, the intricately designed thimbles and the Houdini-themed playing cards that looked as if they’d been there for at least thirty years. Antiques Roadshow would have a field day in here, she realized, as she picked up a figurine of a ballet dancer. It was heavy, possibly pewter, and she wondered who would want it as a souvenir of their time in a Cornish village. Not that she had the nerve to ask Myrtle about her shop-stocking policy. It was clear that the older woman wasn’t a fan of newcomers to the village. Or, at least, not a fan of her.

‘What y’after?’ Myrtle called, after a couple of minutes.

‘Picking up some biscuits,’ Charlie called back.

‘Not down there. Over by the tea and coffee.’

Charlie was about to respond when the bell dinged and a young voice said, ‘Morning Mrs Gordon.’

Myrtle’s voice softened. ‘Myttin da, Jonah. What can I help you with?’

Charlie had established, after a couple of confusing encounters, that “myttin da” meant good morning in Cornish.

‘We need some more sun lotion,’ Jonah said. ‘Dad asked me to come and get it.’

‘Next to the toilet paper.’

‘Cheers. How are you anyway, Mrs Gordon?’ Charlie thought Jonah sounded far too young to be asking such polite questions.

‘Not too bad, cheel. And yourself?’

‘I’m grand, thanks.’

Charlie peered around the corner of her aisle. Jonah, the cheel – or child, looked about eleven, with his blond hair spiky at the front, a bold yellow T-shirt and his legs, below shorts, as thin as sticks.

Jonah turned towards her and held his arm out. ‘I’m Jonah. My mum and dad run SeaKing Safaris from the jetty. Nice to meet you. You’re staying with Juliette and Lawrence, aren’t you? It’s your bus that’s caused a stir, isn’t it?’

‘Wow. News travels fast here.’ Charlie shook his hand.

‘Bleedin’ bus,’ Myrtle muttered. ‘What’s it for, anyway? Driving grockles around?’

Charlie frowned.

‘She means tourists,’ Jonah said, grinning. ‘We take the grockles out on the water, and you’re going to drive them around in your bus.’

‘Unless you are one,’ Myrtle added, drumming her fingers on the table. ‘Juliette said you were staying a few weeks. Tha’ right? Not longer?’

‘I’m going to see how it goes,’ Charlie said, her palms suddenly slick with sweat. Why was everyone so keen for her to leave so quickly? So much for a relaxing holiday.

‘What’s your dog’s name?’ Jonah asked. ‘He’s a Yorkipoo isn’t he? A cross between a Yorkshire terrier and a poodle.’

‘That’s right. He’s called Marmite.’

‘Great name,’ Jonah said, laughing.

‘Bleddy ridiculous if y’ask me,’ Myrtle muttered. ‘Dog and name.’

Charlie wondered if she really needed biscuits after all.

‘You should come on one of our SeaKing trips, if you’re staying for a while,’ Jonah said. ‘They’re great fun, and you get to see all sorts of wildlife. Here’s a card.’ He turned back to the shop counter where Myrtle had a plastic stand full of local business cards and leaflets: The Eden Project, Land’s End, Trebah Garden and SeaKing Safaris.

‘I’d like that,’ Charlie said, taking the card. It seemed Jonah knew how to ride above Myrtle’s curtness. He might only be young, but she could learn a thing or two from him.

‘We’re not too busy during the week,’ he added, not meeting her eye. ‘But if you’re desperate for a weekend slot, I’m sure we could fit you in then, too. Now that you’re local.’

‘Great. I’ll check my calendar.’

Charlie waited while he paid for the sun cream and left, flashing her and Myrtle a winning smile as he closed the door behind him. She put her biscuits on the counter.

‘Lovely lad, that one,’ Myrtle said. ‘Solid head on young shoulders.’

‘Are the safaris any good?’ Charlie blurted, shocked that she was suddenly being spoken to like an equal.

‘Never bin,’ Myrtle admitted. ‘Don’t particularly have sea legs, which isn’t ideal, I know, living somewhere like here. But they’ve a good reputation. You should take ’im up on it. They could do with a few more customers.’

‘I got that impression,’ Charlie said quietly.