По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

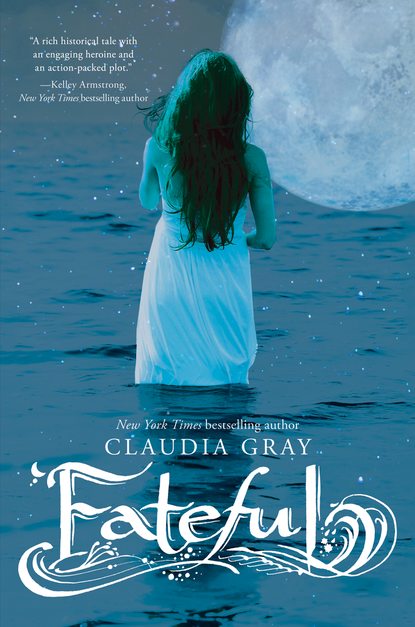

Fateful

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But I can’t shake the thought of it until I realize, all in an instant, that this is the last night I will ever spend in England.

That pulls me into the here and now as nothing else could. I tug my thin blanket more securely around myself and think of everything I’m leaving behind. My home village. Mum. The wheat fields where I used to play. Daisy and Matthew. Everything from my life before. The voyage before me seems more perilous and frightening than anything that happened in the alley.

Yet I know that this is the best chance I’ll ever have to make a new life for myself. Quite possibly it’s the only chance.

No, it’s not too late for me to turn back. But I won’t.

Chapter 2 (#u8c0857c3-555f-5905-b0d4-05fecd7554af)

APRIL 10, 1912

It’s a fine spring morning at the seaside—the sort of thing I’ve dreamt of my whole life. Novels describe the scene by saying that the air is fresh and the blue water dappled with sunlight. I’ve pictured it a thousand times, up in my dark attic. This morning, the very first thing I thought was, At last I will see the ocean.

But the ocean isn’t blue, not this close to land; it’s the same silt-brown color as the millpond, except with an eerie greenish cast to the waves. The harbor is no peaceful oasis for a young girl to stroll; instead it’s more packed with people than the streets were last night—poor people, rich ones, fine lace up against coarse weave, and the smell of sweat thicker in the air than that of seawater. People shout at one another, some happy, others impatient or angry, but the fevered energy of the throng makes it hard to tell which is which. Crammed in the water are as many ships as could be made to fit, including our liner—the largest of them all. The ship is the only thing I see here that’s actually beautiful. Stark black and white, with vibrant red smokestacks reaching into the sky. It’s so enormous, so graceful, so perfect in its way that it’s hard to think of it as anything built by human hands. It looks more like a mountain range.

At least, more like the way novels describe mountain ranges. I’ve never been to one of those either.

“Enough dawdling, Tess,” says Lady Regina, who, as she is fond of reminding everyone, is the wife of my employer, the Viscount Lisle. “Or do you want to be left on the dock?”

“No, ma’am.” Caught daydreaming again. I’m lucky Lady Regina doesn’t light into me about it the way she usually does. Probably she has spied one of her society friends in this crowd and doesn’t want to be seen dressing down a servant in public.

“Mother, you forget.” Irene—the elder daughter of the family, precisely my age, with a face as wholesome as it is plain—gives me an uncertain smile. “You ought to call her ‘Davies,’ now that she’s my ladies’ maid. It’s more respectful.”

“I’ll give Tess respect when she’s earned it.” Lady Regina looks down her long nose at me, as I hurry to catch up. I readjust my grip as I go; none of the hatboxes are that heavy on their own, but it’s a bit much to handle four at once. Fashion has made hats large this year.

“Is that Peregrine Lewis?” says Layton, the lone son and heir of the Lisle family. He’s long and lean, nearly bony, with sharp shoulders and elbows. He peers through the people around us and smiles so that his thin mustache curls. “Seeing his aunt off, I suppose. Polishing her trunks and begging for postcards. The way he licks her boots and fawns for her! It’s vile.”

“He won’t inherit his fortune from his parents, so he must be attentive to the family he has.” Irene glances up at her brother; her lace-gloved hands knotted together at her waist. She is always so shy, even when she’s trying to defend another. “He hasn’t had your advantages.”

“Still, one must have some pride,” Layton insists, oblivious as ever to the fact that he’s following his mother like an obedient lapdog.

Next to me, Ned mutters, “Noodle.”

This one word makes me bite my lip to hold in the laugh. It’s a nickname Ned gave Layton below stairs, and it’s stuck: Layton is just that skinny, that pale, and that limp. He was almost handsome during his university years; I used to have a bit of a crush, before I was old enough to know better. But the bloom of youth is fading for him much faster than it does for most.

“You’re lucky to have a position at all, disrespectful as you are.” Mrs. Horne, even grumpier than usual, glares at both of us as she shepherds her charge along—little Beatrice, Lady Regina’s change-of-life baby. Only four years old, Beatrice is wearing a straw hat bedecked with ribbons that cost more money than I make in a year. “Both of you, look lively. It’s an honor to be brought on a journey such as this, and like as not the most excitement you’ll ever have in your lives. So attempt to do your work properly!”

This won’t be the most excitement I’ll ever have, I swear to myself. First of all, last night—whatever happened with the wolf and the handsome young man—well, I don’t know what else you’d call it, but it was exciting.

More than that, though, I have plans for my future. Plans more thrilling than any life Horne’s ever dreamed of.

But I mustn’t smile. I imagine the old oil paintings that hang on the walls of Moorcliffe, those moldy ancestors in the fashions of another century, imprisoned by frames dripping with gilt. My face needs to be as serene as theirs. As unreadable. The Lisle family and Mrs. Horne must not suspect.

Ned and I do what Mrs. Horne says and hurry along in the family’s wake, as much a part of their display of wealth and power as the clothes that they wear. He’s Layton’s valet, a job I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy, much less dear friendly Ned. He has a long, thin face, ginger hair, and ears like the handles on a milk jug, and yet he’s charming despite his plain face. Thanks to the isolation of life at Moorcliffe, Ned’s one of the few young men I know—one of the only ones I’ve ever known. But we’ve never had eyes for each other. Honestly, after so many years in service together, he feels more like a brother.

I’ve known Mrs. Horne as long as I’ve known Ned, so perhaps I ought to say that she feels more like a mother to me. She doesn’t feel like anybody’s mother, though. It’s impossible to imagine anyone as dry and joyless as Mrs. Horne having given birth to anything, or doing what you have to do to get with child in the first place. (We call her Mrs., but it’s an honorary title; you don’t have to have a husband to be a Mrs., just really old, so Mrs. Horne counts.) She’s the ladies’ maid for Lady Regina, and essentially has the role of housekeeper at Moorcliffe. Nobody among the servants outranks her except the butler, who’s too senile to matter much.

Most of the time, Mrs. Horne terrifies me. She has total power over my life—how much food I get to eat, how many hours I get to sleep, whether I stay in the house to work or get cast out to starve.

But not anymore, I think, and it’s all I can do not to smile into her shriveled, smug face. One week from now, everything will be different.

As we get closer, walking becomes easier. We’ve made it through the passersby, the curiosity seekers; now, everyone is moving in the same direction, flowing onboard. The ship looms over us, taller than the church steeple, taller than anything I’ve ever seen. It seems larger and more majestic than the mud-colored ocean.

Lady Regina waves at one of her society friends, then says, too casually, “Horne, you ought to know that we’ve put the three of you in third class. I understand that the stewards will show you how best to reach us.”

Ned and I can’t resist looking at each other in dismay, and even Mrs. Horne’s thin lips twist in a poor effort to hide her disappointment. When the Lisle family last took a sea voyage a decade ago, the servants stayed in first class with them—feather beds soft as clouds, they said, and more food than you’d ever seen on your own table in your life. We’d hoped for the same. Some people make their servants travel second class; third class is unheard of.

“We’ll be penned down below with a lot of damned foreigners,” Ned mutters. It does sound dreadful, but I remind myself how little it matters.

Layton waves at their friends—approaching now, no doubt fellow passengers. They will have several days on the ocean to talk to one another, but of course they must pay each other every compliment immediately. My arms ache, and I want nothing more than to lay the hatboxes on the ground while we wait. Irene wouldn’t mind, but Mrs. Horne wouldn’t have it. I call on the muscles I have from years of scrubbing floors to see me through.

Then Lady Regina says, “Tess, set those hatboxes down. Mrs. Horne can see to them.”

Mrs. Horne looks put out, probably because she’s now got to handle a small child and four hatboxes. I do what Lady Regina says straightaway and present myself for whatever task she has in mind—because it’s not even worth asking if she saw I was tired. She wouldn’t care. The only reason I get to lay one piece of work aside is to take up another.

Lady Regina snaps her fingers at one of the porters she hired to help, and he hands me a carved wooden box—heavier than all the hatboxes put together. What can they have in there? I manage to grip the small iron handles, though the twists of the metal press into my palms so sharply that they burn. “Yes, milady?” I say. The words come out breathy, as if I’d been running uphill; last night I was too unnerved by the strange incident with the wolf to sleep well, and my exhaustion is showing earlier than usual.

“This needs to be placed in our suite immediately,” Lady Regina says. “I’m uncomfortable leaving it on the dock so long—there are rough characters about. The stewards onboard will show you the way. We’ve arranged for a safe in our cabin; that’s where you’re to put the box. Don’t go leaving it on a table. Am I understood?”

“Yes, milady.” I’m never meant to say anything else to her besides “yes” and “no.”

Lady Regina stares down at me as though I have deviated from the rules in some way. She is a handsome woman, with vibrant beauty that didn’t come down to her daughter—lustrous brown hair and an aquiline nose. Her wide-brimmed hat is thick with plumes and silk flowers, a striking contrast to my shabby black maid’s dress and white linen cap.

“I don’t like sending you to do this alone,” she says sharply. “But I don’t suppose you can manage as many boxes as Ned, and besides—you won’t run off, will you?”

“No, milady.”

Her full lips curl into a contemptuous smile. “I trust you’re a better sort than your sister.”

It feels like scalding water being poured over me, or perhaps like being thrown outside into a snowdrift on an especially cruel winter’s day—something so shocking the body hardly knows how to take it in. My skin burns with rage, as though it’s too tight for me, and my mouth goes dry. I’d like to rip that hat off Lady Regina’s head. I’d like to rip her hair out with it.

I say, “Yes, milady.”

As I go, I feel a strange wave of dread—as though I were back in that alleyway last night. Hardly likely to find a wolf stalking here, amid the ship’s crowd. And yet I feel something prickling along my neck and back, the way I imagine a rabbit knows the cat is watching.

The weight of the box pulls at the joints of my arms, but it’s worth it for a few moments of escape. Or so I tell myself. In truth, it’s a little frightening to be on my own in a crowd like this—more people than I’ve ever seen in one place, all of them pushing and shoving. Also, I can’t tell precisely where I’m supposed to go. There is an entry for first-class passengers, another for third class—going to different decks of the ship altogether. I look down at my burden. Which of us counts more: me or my employers’ possession?

Then I feel it again, that prickle at the back of my neck. The hunter’s eyes on its prey. I glance behind me, expecting to see—what? The wolf from the night before? The young man who rescued me, then told me to flee for the sake of my life? I see neither. In the crush, perhaps I can’t see them, but then they wouldn’t be able to see me either. But someone’s watching. I know he’s there, down deep within me, in the place that doesn’t respond to thought or logic, just pure animal instinct.

Someone in this crowd of strangers is watching me.

Someone is hunting me.

“Lost your way, miss?” says a bluff sort of man, with red cheeks and sky-blue eyes. His voice makes me jump, but the interruption is welcome. He wears what I believe is an officer’s uniform, so why he’s speaking to the likes of me, I can’t imagine. But his voice and face are kind, and I feel safer having somebody to talk to, no matter who it might be.

“I’m to deliver this to my employers’ cabin,” I say. “I’m in the service of the Viscount Lisle’s family.”

“Then it’s first class for you.”