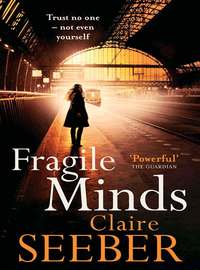

Fragile Minds

‘OK.’ For once he’d fed her enough for her to be happy to hang up. ‘Thanks, Daddy. Love you.’

‘Where are you, Lorraine?’ He stood now.

‘Berkeley Square. I was on my way to the TV place.’

He could hear pure terror in her voice; sensed her trying to suppress panic.

‘Are you OK?’

‘Yes. But – I don’t know what to—’ She was fighting tears. He could hear car alarms jostling for air space. ‘What to do.’

‘Call Control.’ Silver tucked the phone beneath his ear and reached for the remote, snapping the television on. Nothing yet. ‘I will too. And don’t do anything stupid.’

He rang Control; they knew already. He hung up. His phone rang again. It was Malloy.

‘You’d better get down here, Joe. It’s a fucking disaster.’

An appalled Philippa stood behind him as they watched the images begin to unfurl on the television. The tickertape scrolling on the bottom of the screen ‘Breaking News’; the nervous presenter, the ruined bank, the burnt bus, the smart London square now home only to distress and panic. Silver felt that familiar twist in the belly, the lurch of adrenaline that marked crisis.

‘Oh dear Lord,’ Philippa whispered. ‘Not again.’

Eyes glued to the screen, mobile clamped to his ear, Silver watched for a moment. The buzz, the rush; what he lived for. Julie and the stinking gym and the irritation Lana caused him faded entirely. He spoke to his boss.

‘I’m on my way.’

FRIDAY 14TH JULY CLAUDIE

At Natalie’s neat little house in the suburbs, Ella at least was happy to see me, demonstrating her hopping on one leg, her fair curls bouncing up and down, chunky and solid as her mother but far more cuddly.

‘Good hopping,’ I admired her. ‘Can you do the other side?’ But she couldn’t really, despite gallant efforts.

‘Please, Auntie C, can we play Banopoly?’

‘Banopoly?’ She meant Monopoly. ‘Of course. I’d love to.’

‘You can be the boot if you like,’ she said kindly, swinging on my hand. I agreed readily, because I felt like an old boot right now, and it suited me just fine to not think about real life for a moment.

‘Claudia’s hurt, Ella,’ Natalie said, but her heart wasn’t in it. She was so transfixed by the television, by the rolling news bulletins, that she wasn’t concentrating on either of us, so Ella and I sat in the kitchen, away from the television, and had orange squash and digestives as we set the Monopoly board up. In the end, I was the top hat and Ella was the dog, and I let her buy everything, especially the ‘water one with the tap on’ because I knew if she lost, her bottom lip would push out and she would cry. And I found if I didn’t move too suddenly or dramatically, the pain in my head was just about bearable.

At twelve o’clock Natalie washed Ella’s hands and face and took her round to her school nursery for the afternoon session.

‘Will you be here when I get back, Auntie C?’ Ella asked solemnly. ‘We can watch Peter Pancake if you are.’ And I smiled as best I could and said probably. She had once informed me that my complicated name was actually a man’s, and she had long since stopped struggling with it.

‘Of course you’ll be here,’ Natalie snapped, ‘where else are you going to go?’ and we looked at each other in a way that meant we were both acknowledging the reason why I wouldn’t be anywhere else.

‘And of course, we want you here,’ Natalie managed a valiant finish, retying her fussy silk scarf under her chin.

As the door shut behind them, I slid open the French windows and stood in the garden and tried very hard to breathe deeply like Helen had taught me. Natalie’s pink and green garden was so well regimented, just like everything else in her life, that it felt stifling. The air was heavy, rain was on its way, and a strange hush seemed to have descended. Everyone staying inside and a hush that had settled over the whole city – as if we were all waiting. I felt very small suddenly; tiny, a mere dot on the London landscape.

I made myself tea and I put a lot of sugar in it, and then I tried and tried to ring Tessa, but she wasn’t answering; her phone wasn’t even on. No one picked up at the Academy either, so eventually I gave up, and switched on the News again.

MASSIVE EXPLOSION IN CENTRAL LONDON scrolled across the bottom of the screen, and a reporter who looked a little like a rabbit in the headlights informed viewers nervously that Berkeley Square had been hit by some kind of explosion but at the moment no one knew if it was a bomb or a gas main that had blown up. There was no more information, but then numbers were listed for those worried about friends or family; and we were all asked to stay at home.

‘Do not attempt to travel in central London. As a precaution, police have shut down all public transport systems for the moment. We reiterate, it is only a precaution, but the advice is to please remain at home unless your journey is absolutely necessary,’ the dark-skinned reporter warned us gravely, before throwing questions to a sweaty terrorism expert who began to hazard guesses at the cause of the explosion.

My phone rang again. This time I did answer it, praying it was Tessa.

‘Claudie. I’ve been so worried. What the hell’s going on?’ Rafe sounded furious. ‘I thought you’d be here when I got back.’

‘London’s gone mad,’ I said quietly. ‘It’s all exploding.’

‘Never mind that – what the hell happened last night? I waited for you in the restaurant, and you never came, and then there you were, on my doorstep, frozen and practically unconscious. Were you drunk?’ He was accusatory.

‘No,’ I replied. ‘Definitely not drunk.’

‘What then?’

‘I can’t remember, Rafe. I just – I had this terrible migraine, and then—’

‘What do you mean you can’t remember?’

Now was not the time to tell him about the splitting. In fact, I was realising there was never going to be a time to tell him about it. And yet, I was terrified that I was sliding backwards, back to the place I’d gone when Ned died, when my world had caved in and the nightmare became reality.

‘Rafe, one thing—’

‘Yes?’

‘Who is she?’ I stared at my bare feet. The ground beneath them was shifting again and life was not going to be the same now, I realised. My silver nail varnish was very old and chipped. I must do something about it, I thought absently.

‘Who?’

‘The owner of the pink toothbrush. In the bathroom cupboard.’

‘No one.’ There was a long pause. ‘It’s not what it looks like. I mean, she’s just an old friend.’

‘Yeah right.’ I felt so tired I could hardly speak.

‘She stays sometimes when she’s in town. That’s all.’ He was both contrite and angry in turns, as if he hadn’t quite decided the best form of defence.

‘It’s fine. Look, I’ve got to go, Rafe. It’s up to you what you do.’

‘Claudie—’

I hung up. I tried Tessa again. Nothing.

I was frightened. I was fighting panic. Why couldn’t I remember this morning clearly? I debated ringing my psychiatrist Helen, but I wasn’t sure that was a good idea. I couldn’t go running to her every time something went wrong. And she might think I was deluded again, and I wasn’t sure I could bear that.

I switched the News on again, the explosion still headlines, the first pictures I had seen. A bus lay on its side in hideously mangled glory, like a huge inert beast brought down by hunters. The newsreader emitted polite dismay as I stared at the pictures in horror.

‘Speculation is absolutely rife in the absence of any confirmation of what exactly rocked the foundations of Berkeley Square this morning at 7.34 a.m. Immediate assumptions that it was another bomb in the vein of the 7/7 explosions five years ago are looking less likely. Local builders were working on a site to the left of the square, the adjacent corner to the Royal Ballet Academy, on a new Concorde Hotel. The site is situated above an old gas main that has previously been the subject of some concern. The Hoffman Bank has been partially destroyed; at least one security guard is thought to have been inside. So far, Scotland Yard have not yet released a statement.’

At least, thank God, the Academy seemed untouched by the explosion. I tried Tessa one more time, and then Eduardo; both their phones went to voicemail now. I turned the News off and went upstairs, craving respite. I heard Natalie and Ella come in, Ella chattering nineteen to the dozen. I felt limp with exhaustion. I’d tried so hard to stay in control recently, and yet something had gone very wrong.

In the bathroom I rifled through Natalie’s medicine cabinet: finding various bottles of things, I took what I hoped was a sleeping pill. I went to the magnolia-coloured spare bedroom with the matching duvet set, shut the polka-dot curtains against the rain that had just started, and invited oblivion in.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY KENTON

Silver had insisted DS Kenton was checked out by the paramedics, but she knew that she wasn’t injured, only shocked. He wanted her to go home, but Kenton wasn’t sure being alone was the right thing. She kept seeing that hand in the middle of the road, bloody and raw, and the body sliced completely in two, and every time she saw it, she had to close her eyes. She felt numb and rather disconnected from reality; she sat in the station canteen nursing sweet tea and it was a little like the scene around her was a film, all the colours bright and sort of technicolour.

The person Kenton really wanted to speak to was her mother, but that was impossible. So she rang her father, but he was at the Hospice shop in town, doing his weekly shift, and he couldn’t work his mobile phone properly anyway, so he kept cutting her off, until she gave up and said she’d call later. She didn’t even get as far as telling him about her trauma. She drank the tea and stared at the three tea leaves floating at the bottom, and then on a whim, she rang Alison.

Alison didn’t answer, so she left her a rather faltering, stumbling message.

‘Hello. It’s me.’ Long pause. Not wanting to sound presumptuous she qualified: ‘Me being Lorraine.’ Oh God, now she sounded like an idiot. ‘I’ve been in a – in the – I was there when Berkeley Square, when it exploded.’

She panicked and hung up.

On the other side of the canteen she saw Silver stroll in, as calm and unruffled as ever, his expensive navy suit immaculate, not a hair out of place. She could understand why women’s eyes followed him; not particularly tall, not particularly gorgeous, perhaps, but just – assured. Commanding, somehow.

‘Lorraine.’ He bought himself a diet Coke from the machine behind her. ‘How you feeling? Time to go home, kiddo?’

‘I don’t know.’ Her voice was trembly. She cleared her throat. ‘I keep thinking about the hand.’

‘The hand?’ Silver snapped the ring-pull on the can and sat opposite her.

‘There was a hand,’ she whispered. ‘In the road. Just lying there. There were – there were other – bits.’

‘Right.’ He looked at her, his hooded hazel eyes kind. ‘Nasty. Now, look. Go home, get one of the lads to drive you if you want – and call me later. We’ll have a chat. Take the weekend off. And you should think about seeing Merryweather.’

‘I’m not mad,’ Kenton was defensive.

‘No, you’re in shock. Naturally. And you did a great job, Lorraine.’ His phone bleeped. ‘A really great job.’ He checked the message. ‘Explosives officers are at the scene now. Got to go. Call me, OK?’

‘OK.’ She sat at the table for another few minutes. Sighing heavily she began to gather her things. Her phone rang. Her heart skipped a beat. It was Alison.

‘Lorraine.’ She sounded appalled. ‘Oh my God. Are you OK? What happened?’

Kenton felt some kind of warmth suffuse her body. Alison had rung back. She walked towards the door, shoulders back.

‘Well, you see, I was on my way to a TV briefing,’ she began.

MONDAY 17TH JULY CLAUDIE

I woke sweating, like a starfish in a pool of my own salt. A bluebottle smashed itself mercilessly between blind and window, its drone an incessant whirr into my brain. It had been a long night of terrors, the kind of night that stretches interminably as you hover between sleep and consciousness, unsure which is dream and which reality.

‘Where are you? Where are you? Why are you not answering? I’m scared, Claudie, I can’t do it, Claudie …’

My heart was pounding as I tried to think where the hell I was. I tried to hold on to the last dream but it was ebbing away already, and fear was setting in. Momentarily I couldn’t remember anything. Why I was here. I was meant to be somewhere else surely – I just couldn’t think where.

I had spent the weekend at Natalie’s, against my better judgement but practically under familial lock and key. Natalie was truly our mother’s daughter, and I’d found the whole forty-eight hours almost entirely painful. She had fussed over me relentlessly, but it was also as if she could not really see me; as if she was just doing her job because she must. In between cups of tea and faux-sympathy, I’d had to speak to my mother several times, to firstly set her mind at rest and then to listen to her pontificate at length on what had really happened in Berkeley Square, and whether it was those ‘damned Arabs’ again. And all the time she’d talked, without pausing, from the shiny-floored apartment in the Algarve where she spent most of her time now, and wondering whether she should come over, ‘Only the planes mightn’t be safe, dear, at the moment, do you think?’ I’d kept thinking of Tessa and wondering why she didn’t answer her phone now.

Worse, it had poured all weekend, trapping us in the house. The highlight was Ella and the infinite games of Connect 4 we played, which obviously I lost every time. ‘You’re not very good, are you, Auntie C?’ Ella said kindly, sucking her thumb whilst my sister scowled at her ‘babyish habit’. ‘Let her be, Nat,’ I murmured, and then Ella let me win a single round.

The low point was – well, there was a choice, actually. There had been the moment when pompous Brendan drank too much Merlot over Saturday supper and had then started to lecture me on ‘time to rebuild’ and ‘look at life afresh’ whilst Natalie had bustled around busily putting away table-mats with Georgian ladies on them into the dresser. I had glared at my sister in the hope that she might actually tell her husband to SHUT UP but she didn’t; she just rolled table napkins up, sliding mine into a shiny silver ring that actually read Guest. So I sat trying to smile at my brother-in-law’s sanctimonious face, thinking desperately of my little flat and the peace that at least reigned there. Lonely peace, perhaps, but peace nonetheless. After a while, I found that if I stared at Brendan’s wine-stained mouth talking, at the tangle of teeth behind the thin top lip, beneath the nose like a fox’s, I could just about block his words out. For half an hour he thought I was absorbing his sensitive advice, instead of secretly wishing that the large African figurehead they’d bought on honeymoon in the Gambia (having stepped outside the tourist compound precisely once, ‘Getting back to the land, Claudie, and oh those Gambians, such a noble people, really, Claudie; having so little and yet so much. They thrive on it’) would crash from the wall right now and render him unconscious.

The second low came on Sunday morning, just after I had turned down the exciting opportunity to accompany them to the local church for a spot of guitar-led happy clapping.

‘Leave Ella here with me,’ I offered. My head was clearer today, not as sore and much less hazy than it had felt recently. The paranoia was receding a little. ‘It must be pretty boring for her, all that God stuff.’

‘Oh I can’t,’ Natalie actually simpered. ‘Not today. We have to give thanks as a family.’

‘What for?’ I gazed at her. She looked coy, dying to tell me something, that familiar flush spreading over her chest and up her neck and face. I looked at her bosom that was more voluptuous than normal and her sparkling eyes and I realised.

‘You’re pregnant,’ I said slowly.

‘Oh. Yes,’ and she was almost disappointed that she hadn’t got to announce it, but she was obviously wrestling with guilt too. ‘Are you OK with that?’

‘Of course. Why wouldn’t I be?’ I moved forward to hug her dutifully. ‘I’m really pleased for you.’

Natalie grabbed my hands and pushed me away from her so she could search my face earnestly. ‘You know why. It must be so hard for you.’ A little tear had gathered in the corner of one of her bovine brown eyes. ‘I – I’d like you to be godmother though,’ she murmured, as if she was bestowing a great gift. ‘It might, you know. Help.’

‘Great,’ I smiled mechanically. And I was pleased for her, of course I was, but nothing helped, least of all this, though she was well-intentioned; and I knew it was impossible for anyone else to understand me. I was trapped in my own distant land, very far from shore; I’d been there since Ned closed his eyes for the last time and slipped quietly from me. ‘Thank you.’ And I hugged her again, just so I didn’t have to look at the pity scrawled across her face.

‘If it’s a boy,’ she started to say, ‘we might call him—’

I heard an imaginary phone ringing in my room upstairs. ‘Sorry, Nat. Better get it, just in case—’ I disappeared before she could finish.

Whilst they were at church, I gathered my few bits and pieces and wrote her a note. I was truly sorry to leave Ella, I loved spending time with her, but I needed to be home now. I needed to be far, far away from my well-meaning sister and the suffocating little nest she called home.

And so here I lay, alone again. In the next room, the phone rang and I heard a calm voice say ‘Leave us messages, please.’

My voice, apparently; swiftly followed by another – male, low. Concerned. I attempted to roll out of bed, but moving hurt so much I emitted a strange ‘ouf’ noise, like the air being pushed from a ball. I lay still, blinded by pain, my ribs still agony from where I’d apparently fallen on Friday. When it subsided, I tried again. Wincing, I stumbled into the other room, snatched the receiver up.

‘Hello?’

‘You’re all right.’ The accented voice was relieved. ‘Thank God.’

‘Who – who is this?’ I caught my reflection in the mirror. Round-eyed, black-shadowed; face scraped like a child’s. My bare feet sank into the sheepskin rug I hated.

‘Claudie. It’s Eduardo. I didn’t know if you’d be there. Your sister called. I thought you might be away.’

‘Away?’ My brow knitted in concentration. ‘Eduardo.’ I made a concerted effort. Eduardo was head of the Academy. In my mind I conjured up an office, papers stacked high, a man in a grey cashmere v-neck, big hands, dark-haired, moving the paperweight, restacking those papers. ‘Oh, Eduardo.’ I sat heavily on the sofa. ‘No, I’m here. Sorry. I think I – I find it hard to wake up sometimes.’

I had got used to a little help recently, the kind of pharmaceutical help I could accept without complication.

‘I’m ringing round everyone to check. You’ve obviously heard what has happened?’

‘About the explosion? Yes,’ my hands clenched unconsciously. ‘Awful.’

‘Awful,’ he agreed. ‘They have only just let us back into the school. But – well, it’s worse than awful, Claudie, I’m afraid.’ I heard his inhalation. ‘There is some very bad news.’

Bad news, bad news. Like a nasty refrain. I stood very quickly, holding my hands in front of me as if warding something off.

‘I’m sorry.’ I sensed his sudden hesitation. ‘I should have thought. Stupid.’ He’d be banging his own head with the heel of his hand, the dramatic Latino. ‘My dear girl—’

‘It’s OK.’ I leant against the wall. ‘Just tell me, please.’

‘It’s Tessa.’

‘Tessa?’ My cracked hands were itching.

Tessa, with her slight limp and her benign face, her hair pulled back so tight. My friend Tessa who had somehow seen me through the past year; with whom I had bonded so strongly through our shared sense of loss. My skin prickled as if someone was scraping me with sandpaper.

‘Tessa’s dead, Claudie. I’m so sorry to have to tell you.’

Absently, I saw that my hand was bleeding, dripping gently onto the cream rug.

Emboldened by my silence, he went on. ‘Tessa was killed outside the Academy. Outright.’ He paused. ‘She wouldn’t have known anything, chicita.’

‘She wouldn’t have known anything,’ I repeated stupidly. My world was closing to a pin-point, black shadows and ghosts fighting for space in my brain.

‘I’m so sorry to have had to tell you,’ he said, and sighed again. ‘I am just pleased for you that you are not here this week. It is a very bad atmosphere. I think it’s good your sister has arranged for you to have this time off.’ I hadn’t had much choice in the matter: Natalie had taken over. ‘Try to rest, my dear. See you soon.’

Tessa was dead. Outside the birds still sang; somewhere nearby a child laughed, shrieked, then laughed again. The rain had stopped. Someone else was playing The Beatles, Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds; Lennon’s voice floated through the warm morning, like dust motes on dusk sunshine. Death was in the room again. I closed my eyes against the cruel world, a world that kept on turning nonetheless, a sob forming in my throat. I imagined myself now, stepping off the bus, fumbling with the clasp of my bag, raising my hand in greeting, happy to see her …

The birds still sang, but my friend Tessa was dead – and I couldn’t help feeling I should have saved her.

TUESDAY 18TH JULY SILVER

7 a.m., and Silver was exhausted already. It had been a horrendous weekend; the worst kind of police work. Counting the dead, identifying and naming the corpses: or rather, what was left of them. Recrimination and finger-pointing and statistics that meant nothing. Contacting the families, working alongside the belligerent and somewhat over-sensitive Counter Terrorist Branch; waiting for the Explosives Officers who were struggling due to the amount of debris caused by the Hoffman Bank partially collapsing, hampered by torrential rain all weekend.

Images stuck to the whiteboards at the end of the office made him wince; the carnage, the tangle of metal, strewn rubber, clothing, the covered dead and the walking wounded. The life-affirming sight of human helping human – only wasn’t it a little late? Too late to make a difference: one human had hated another enough to do this – possibly … A gas leak was still being mooted, but Silver knew the drill, knew this was to prevent panic spreading through the city, another 7/7, another 9/11, the stoic Londoner weary of it all already. The Asians fed up of ever-wary eyes, the Counter Terrorist Branch overworked and frankly baffled. How do you keep tabs on invisible evil that could snake amongst us unseen? Silver was hanged if he knew.

He yawned and stretched as fully as his desk allowed. That bastard Beer was calling him, whispering lovingly in his ear over and again. He needed a long cold pint, smooth as liquid gold down his thirsty aching throat. He swore softly and checked the change in his pocket. Out in the corridor, he bought himself his fifth diet Coke of the night and unwrapped another packet of Orbit. Distractions. He wished he felt fresher, more alert, but he felt tired and rather useless. However much he preferred work to home, he wished himself there now, asleep, oblivious to the world’s inequities. Leaning against the wall wearily, he drank half the can in one go.

Craven popped his balding head out of the office. ‘Your wife’s on the phone.’

‘Ex-wife,’ Silver said mechanically.

In an exercise of male camaraderie, Craven grimaced. ‘Sorry. Ex-wife.’

Silver checked his expensive Breitling watch. Following Craven, he leant over the desk for the receiver. It was early even for her.

‘Lana?’

There was a long silence. He rolled his eyes; he thought he heard a sniff. Lana never cried.

‘What is it, kiddo?’ he tried kindness. He had ignored so many things recently, he was stamping all over his ‘emotional intelligence’ apparently; the intelligence they’d been lectured on recently at conference.