По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

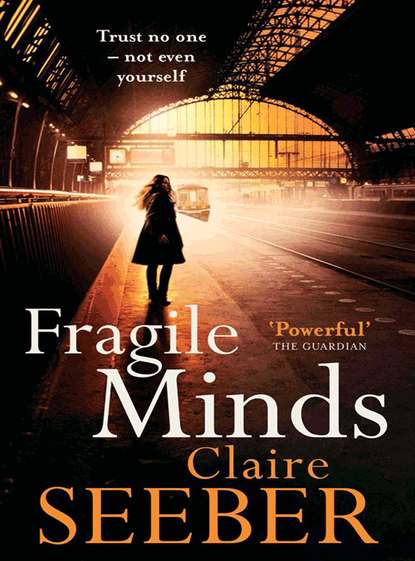

Fragile Minds

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But her concern was unpersuasive. As he lolloped down the stairs two at a time, Silver thought he’d never met anyone who seemed more excited by the apparent disappearance of a friend.

WEDNESDAY 19TH JULY CLAUDIE

The phone woke me with a nasty start at 8 a.m. I held my breath, but it was only Rafe, still seeking forgiveness apparently.

‘Claudia, if you do not ring back by lunchtime, I’m coming round between sittings.’ His voice softened. ‘I saw the thing about Tessa in today’s paper. Such a tragedy.’

I couldn’t help feeling his persistence was more to do with being thwarted than anything more sincere. Rafe did like his own way. Pulling my jeans on, I went down to Ahmed’s on the corner; I bought The Times, a copy of Vogue for the sheer normality of it, a can of Fanta and a Flake, craving sweetness and comfort. I left the shop quickly before Ahmed’s wizened mother could appear through the beaded curtain and ask about my face, which she’d then refer to every day for six months. I hadn’t been out of the flat for two days, I realised, as my feet trod the filthy pavement, and the colours of the day were bright and unreal, piercing my tired brain; as if the rain had washed London clean for once.

I sat beside the open window and drank my drink through a twirly elephant straw I’d found at the back of the cutlery drawer. I breathed in the fresh air, the smell of blossom, the scent of hope; I tried to avoid the tower block that sliced the sky in two before me. I felt a little more normal today; my head wasn’t aching and I felt clearer, but my craving for a cigarette was building again. I had to start denying my fears. I wouldn’t let it happen again, if it was. I’d fight it every step of the way this time.

I read my stars in Vogue, clinging to some vestige of my old life. I looked at the pedigree girls striking odd angular poses, all legs and big hair and surprised eyes. I pulled my own blonde scarecrow-do back and tied it with an elastic band that had held yesterday’s post. Then I scanned the newspaper headlines briefly; they mentioned the ‘Daughters of Light’ claim, but I turned the pages until I found the picture of Tessa, taken from a series the Sunday Telegraph had commissioned of the Academy last year, including Lucie Duffy. The picture showed intense concentration on Tessa’s bony face as she oversaw a class of seniors, black practice skirt flowing from her tall, lean form. I read the tribute. Darcey Bussell had given some flowery comments about the Academy and its brilliant teachers. Prima ballerina Natalia Vodovana had praised Lethbridge’s style, which made me smile wryly as I remembered Tessa’s disparaging views on Vodovana’s ‘showy style and forced line’.

And Lucie Duffy, who had graduated last year and was rocketing up the Royal Ballet’s ranks, was quoted: ‘Tessa Lethbridge was the best.’ I remembered Duffy and her friend Sadie; pretty, spiteful dancers, all about themselves. Sadie, blonde, Northern, tough and horribly bulimic, living in Duffy’s shadow, never reaching the potential of her friend and room mate.

I shut the paper and finished the Flake, tipping my head back to pour the last crumbs into my mouth. I couldn’t have been less like the girl in the technicolour poppy field if I tried. I tried to focus on positive memories, as Helen had taught me. Zoe and I on the beach in Goa last Christmas. Tessa listening; Tessa laughing over crème brulée at Mimi’s. Ned’s hand in mine. Ned’s little hand in mine. Ned’s hand, slipping through mine …

They didn’t work: the positive memories. They never did. The incision was too deep. His hand in mine, clutching so tight – and I, I had let go. I had failed fundamentally as a mother.

Savagely, I pushed the thought away. But the pain when it came was unbearable, like my soul was thrashing around for a refuge – only there wasn’t one. I wanted to pull my hair out, scratch my eyes out: to lacerate myself with pain.

I got up and put another nicotine patch on. I felt better immediately; the craving calmed. I rang the office and left a message for Eduardo, asking if I could come in for a shift or two. I didn’t want to sit here any more, alone with my thoughts and the guilt that was accumulating. I’d be better back at work, occupied; if I sat here any longer alone, I might fall back down. I loved my job; it had been my passion for years, working with the human body, helping people to heal. It had saved me when I had been flailing; it bridged a terrible void.

I filled the old metal watering can at the kitchen sink; I kept seeing myself on the bus on Thursday. Why could I not remember getting to Rafe’s? Where had I been? I was frightened that I was slipping backwards, that was the truth. I contemplated ringing Helen.

As I watered the window-boxes out on the balcony, the scarlet geraniums bright against the overcast sky, the telephone rang again. A swan flew across the canal, brilliant against the murky waters, and landed with elegance.

I thought it would be my boss but it wasn’t.

‘Claudie. It’s nearly time.’ There was a long pause and a sigh. ‘We’re waiting for you now.’

I felt a fierce twist of fear. Transfixed, I gazed at the light blinking belligerently on the machine. I heard the click as the phone was cut off.

Savagely, I pulled the phone out of the wall, dislodging a small cloud of plaster in the process. Someone was angry with me, and I didn’t know why. I had the strangest sensation that my life was shrinking down to this moment – and I had two choices. Run, or face it.

In the bathroom, I scrabbled around for my last few pills. Then I lay on my bed, in the dark, fiddling with the locket on the necklace Tessa had given me; thinking, thinking.

Friday morning was all such a haze still. I had got on the bus outside Rafe’s; I had started towards work. I had this strange idea that was forming, that Tessa had needed me; that I had been summoned …

Thinking, thinking – I fell into a doze.

Dreaming. Tessa and Ned, dancing in a poppy field …

My bedroom door was opening and I was screaming, screaming and—

My sister stood in the doorway, clutching an orange Le Creuset casserole dish, blinking rapidly like a worried rabbit.

‘Oh my God.’ I sat bolt upright on the bed, my heart thudding. ‘I nearly had a heart attack. How the hell did you get in?’

‘I borrowed the spare key from Mum’s,’ she said brightly. ‘I was so worried, Claudia, you haven’t been answering your phone.’

‘Haven’t I?’

‘Don’t be silly. You know you haven’t.’

I didn’t remember her ringing.

‘And I bet you haven’t been eating either. I know you, Claudie Scott.’ She put the dish down on the chest of drawers and opened the blind. ‘Come on, hoppity-skip. Out of bed with you. I’ll put the kettle on.’

She breezed out of the room, retrieving her casserole dish and proudly bearing it before her like a precious icon. At least she was a better cook than our mother.

‘Hoppity-skip?’ I muttered to myself. ‘Dear God.’ But I got out of bed and followed her into the living room, like a child.

‘Your hair needs a brush,’ she said reprovingly, from her station at the kettle. ‘And a trim. I’m surprised you can see out of that fringe. And your roots are showing.’

‘Nat,’ I slumped down at the table. ‘When did you turn into Mum?’

‘Probably when I became one. Now, Earl Grey or builders? Or green. Now that’s very good for you, I’ve read. Cleans your digestive tract. I’ll make some green, and we can have a nice chat.’

‘Do we have to?’ I groaned. ‘I think my digestion’s all right, honestly.’

‘I just wanted,’ her bluster subsided for a moment, ‘I wanted to check you’ve been looking after yourself actually.’

Suddenly she was less sure of herself.

‘Did you?’ I gazed at her. We never talked about my mental state. Natalie found it too shaming.

‘Yes.’ She was too bright. ‘Now, your lovely psychiatrist has been on the phone. Helen, isn’t it? Ever so worried she can’t get hold of you. Has it—’ The brightness was fading; she was struggling now. ‘Has it happened again?’

‘What?’

‘Come on, Claudie.’ She flapped around with the teabags, banging cupboard doors. ‘You know what.’

‘You mean, have I disassociated from reality again?’ I thought of my lost hours. ‘I don’t know,’ I said truthfully.

‘Right.’ She looked supremely uncomfortable.

‘Actually,’ I changed tack midstream. I couldn’t do this with Natalie. ‘I don’t think it has.’

She couldn’t handle it, that much was obvious. Not many people could. Not even my husband, Will – so why put them through it? My own mother had been distraught at losing her three-year-old grandson, but more distraught, I feared, at my own descent into hell. ‘Thank God Phillip’s not here,’ I heard her tell my auntie Jean once, ‘it would have destroyed him to see her like this.’ They’d expected me to be strong, and I failed them too.

‘No. I’m fine,’ I said. I put some cream on my sore hands for something to do.

‘Good,’ she looked infinitely relieved. ‘Also, Mum’s been calling. Can you just ring her back, Claudia? I mean, Portugal is not the other side of the world, is it, love, and she’s not coming back for a while apparently, not unless you need her, she says. Just give her a bit of reassurance, and she’ll leave you alone.’

My little sister and I stared at each other, and then slowly I smiled. Perhaps Natalie did understand a little.

‘Sure. I will. Perhaps I’ll go out and see her.’ The idea of the sun on my weary bones suddenly seemed enticing, although my mother’s incessant chatter and home cooking did not.