По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

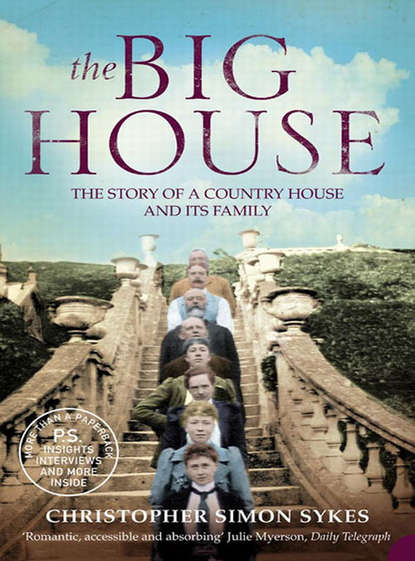

The Big House: The Story of a Country House and its Family

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo) In recognition of his ‘having planted the greatest quantity of Larch Trees’, the secretary, William Ellis, wrote to tell him that ‘you are entitled to make choice of any Book or set of Books not exceeding the price of Five Guineas’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

When John Bigland toured Yorkshire at the end of the first decade of the nineteenth century, his description of Sledmere showed precisely how great a transformation of the landscape had taken place in the relatively short time that Christopher Sykes had lived there.

Sledmere is situated in a spacious vale, in the centre of the Yorkshire Wolds, and may be considered as the ornament of that bleak and hilly district. All the surrounding scenery displays the judicious taste of the late and present proprietors: the circumjacent hills are adorned with elegant farm houses covered with blue slate, and resembling villas erected for the purpose of rural retirement. The farms are in as high a state of cultivation as the soil will admit; and in the summer the waving crops in the fields, the houses of the tenantry elegantly constructed, and judiciously dispersed, the numerous and extensive plantations skirting the slopes of the hills, and the superb mansion with its ornamented grounds, in the centre of the vale, form a magnificent and luxuriant assemblage, little to be expected in a country like the Wolds; and to a stranger on his sudden approach, the coup d’oeil is singularly novel and striking.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was a fitting tribute to Christopher’s great vision.

CHAPTER III The Architect (#ulink_7a4362d5-d507-5e3b-88c1-3be59332e137)

In February, 1783, the month in which the American War of Independence finally drew to a close, Christopher received a letter from his brother-in-law, William. ‘My Sister mentioned in her last’,’ he wrote, ‘that you were looking for a House, I hope you have heard of one by this time that will be comfortable for you at the present, I can’t help wishing very much that the Doctor wou’d give up Sledmere to you, but I conclude that is out of the question.’

(#litres_trial_promo) If only for one reason, this was true: Parson was now an old man in his seventies and suffered from poor health. He had seen little of his son in the previous few years, who, as a result of the war, had taken up a commission as a Captain in Colonel Henry Maister’s Regiment, the East Yorkshire Militia, though while away from home, Christopher had been kept informed as to his father’s condition from regular letters sent to him by the Sledmere butler, John Hopper. Parson suffered constantly from pains in his chest, regular spasms and dreadful gout. ‘He is very Low Spirited and Eats very little,’

(#litres_trial_promo) Hopper wrote in April, 1782, though there were the occasional good days. ‘I have the pleasure to acquaint you,’ wrote Hopper on 15 August, ‘that your Father got out an Airing last Saturday and has continued it every day since, he was at Church on Sunday.’ In a memoir written by my grandfather, he recalled meeting, when he was a child, an old lady who remembered seeing Parson at church, ‘a little old man with a powdered wig carried into Sledmere Church on his footman’s back’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Parson did not recover from his illness, and his death the following year solved Christopher’s housing problem. He survived long enough, however, to be the beneficiary of a great honour bestowed upon him by the King. Writing to Christopher early in February, 1783, Richard Beaumont, his friend and fellow plantsman, told him that he had heard ‘that a Baronet will shortly be created in the East Riding, so saith a Friend connected with the Rulers of the Nation’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Baronetcy to which he referred was to be offered to Christopher as a reward for his contribution to the reclamation of the Wolds. The high esteem in which he held his father is evident from the fact that he chose to turn down the title, insisting that it was conferred upon Parson instead. On 25 February, 1783, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the Rt Hon. Thomas Townshend, signed a patent on behalf of King George III: ‘Our will & pleasure is that you prepare a Bill for our Royal Signature to pass our Great Seal containing the Grant of the Dignity of a Baronet of this our Kingdom of Great Britain unto our trusty and well beloved Mark Sykes, Doctor in Divinity, of Sledmire in our County of York.’

(#litres_trial_promo) So Parson became the Revd Sir Mark Sykes, 1st Baronet of Sledmere.

Amongst the hundreds of letters of congratulation that came pouring in for both the new Baronet and his son was one from Uncle Joseph, who lamented that ‘his poor state of Health will afford him so little enjoyment of this or of almost any earthly Comfort’.

(#litres_trial_promo) They were prophetic words. On 9 September Christopher recorded in his diary, ‘My father taken ill’, and the following Sunday, 14 September, ‘My Dear Father died at 4½ this morning. I got to Sledmere at 8½ not knowing of his illness till the night time at Hull Bank.’ He was buried on 19 September. ‘The Remains of my Dear Father,’ noted Christopher, ‘was taken from Sledmere at 8½ o’clock and was buried at Roos at 6 o’clock in the evening.’

(#litres_trial_promo) His coffin was attended only by his servants, a stipulation he had made in his will. ‘The very painful & lingering life which My Uncle led,’ wrote Parson’s nephew, Nicholas, to Christopher, ‘may make his death be looked upon as a happy release by all his Friends.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

By the end of 1783, Christopher, Bessy and the five children had moved into the big house, unfortunately for them in the middle of an exceptionally cold winter. In an age when most of us live in over-heated houses, it is easy to forget how uncomfortable it must have been to live in a large draughty house in periods of harsh and freezing weather. It was still a number of years before the advent of any kind of central heating, and the inhabitants had to rely on individual fires as their only source of warmth. ‘I hope you all keep well & have plenty of Coals,’ wrote Henry Maister to Christopher in January, 1784, ‘for around a good fire is the only comfortable place’,

(#litres_trial_promo) though the truth is that most fireplaces usually produced more smoke than heat, and the only guaranteed way to keep warm was to wear more clothes. On 3 January, Christopher recorded ‘a heavy storm of snow’ in his diary, and throughout January and February there are regular entries for ‘deep snow’ and sometimes ‘extremely deep snow’. Things finally began to improve on 22 February, when Christopher was able to write ‘began this day to thaw’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

No doubt inspired by the Arctic conditions they had been experiencing, Christopher also set about a new piece of building work at Sledmere, the creation of an ice-house. These buildings, which were de rigueur in most big houses of the day, were an advanced version of a ‘snow-well’ built for the Duke of York at St James’s Palace in 1666. While that had been little more than a pit dug into the ground and thatched with straw, the new models were often architect-designed and vaulted in brick or stone.

(#litres_trial_promo) They were situated close to the nearest large stretch of water – in the case of Sledmere, it would have been the Mere – so that during the winter the ice could be cut and placed in the ice-house, carefully insulated between layers of straw, for use the following summer, when it would have been used primarily for the refrigeration of food as well as for the occasional iced dessert. The design for the Sledmere ice-house came in the form of a working drawing, showing a detailed and carefully labelled section, sent to Christopher in February, 1784 by John Carr, the architect of Castle Farm. It was dug out in July and a sum of 12s. 6d. was entered in the house accounts the following January for ‘filling Ice-House’.

Seventeen eighty-four may well have been a momentous year for Christopher and his family, their feet firmly perched upon the ladder of social ascendancy, but so it was for the outside world too. There was change in the air. The disastrous War of American Independence was over, and the ministry of the man who had presided over it, Lord North, had disintegrated. A new group of radical thinkers was beginning to influence politics, men like Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, Erasmus Darwin and Benjamin Franklin, who believed in the reformation of Parliament and in John Dunning’s famous motion ‘that the power of the Crown has increased, is increasing, and ought to be diminished’. They had found a voice in the short-lived Parliament of Lord Rockingham’s Whig Party and had achieved a number of reforms before his sudden death in July, 1782, including the reorganisation and reduction of the Royal household, the disenfranchisement of revenue officers, and the debarring of government contractors from sitting as MPs.

The short reign of Rockingham’s successor, Lord Shelburne, and the speedy collapse of the ministry which followed – an ill-judged coalition of two implacable enemies, the unpopular Lord North and the Whig, Charles James Fox – allowed King George III to invite a rising young star, William Pitt, to form a Government. Pitt, the second son of the Earl of Chatham, himself Prime Minister over a period of twelve years, made his maiden speech at the age of twenty-one, served in Lord Shelburne’s Cabinet as Chancellor of the Exchequer aged twenty-three, and was only twenty-four when he became First Minister. Though this might seem an extraordinary feat to most people, it would not have surprised his family, whose nicknames for him – ‘William the Great’, when he was a small child, and ‘the Young Senator’, ‘the Orator’ and ‘the Philosopher’ when he was in his teens – suggest that they had a strong hunch he would go far.

(#litres_trial_promo) When aged only seven, his mother had written to her husband, ‘of William, I said nothing, but that was because he cannot be extraordinary for him’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pitt was in the right place at the right time when oratory was becoming more and more a feature of debate. His maiden speech, made on 26 February, 1781, caused the assembled members to prick up their ears, especially since it was made off the cuff as a result of an unexpected call by a number of the opposition, eager to test out the so-called brilliance of Chatham’s son. They were not disappointed. ‘It impressed … from the judgment, the diction and the solemnity that pervaded and characterised it,’ wrote Nathaniel Wraxall, who was present. ‘The statesman, not the student, or the advocate, or the candidate for popular applause, characterised it … All men beheld in him at once a future Minister, and the members of the Opposition, overjoyed at such an accession of strength, vied with each other in their encomiums as well as in their predictions of his certain political elevation.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Indeed Edmund Burke was so overcome with admiration that he is reported as having said ‘he is not merely a chip off the old block, but the old block itself’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was not long before Pitt had the ears of the House whenever he spoke, an honour rarely granted to new young members, and his name soon began to be known to a wider public beyond the benches of the Commons. As early as February, 1783, when he was still only twenty-three, he was the choice of a number of astute politicians to succeed Shelburne, who had resigned after two Government defeats. ‘There is scarcely any other Political Character of consideration in the Country,’ wrote Henry Dundas, ‘to whom many people from Habits, from Connections, from former Professions, from Rivalships and from Antipathies will not have objections. But he is perfectly new ground …’

(#litres_trial_promo) He actually was sent for by the King, but turned down the offer, on the grounds that if he was to come to power it was to be on his own terms. It was a brave and shrewd decision, for when the King asked him a second time the following December and he accepted, he was in an unassailable position. The news was received in the House of Commons with a shout of laughter. It was, after all,

A sight to make surrounding nations stare; A Kingdom trusted to a school-boy’s care.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Any ambitious young man of position would have been swept up in the excitement of the moment, and in the general election of March, 1784 that put Pitt into office, a notorious affair that had gone on for forty days – ‘forty days’ poll, forty days’ riot and forty days’ confusion’ as Pitt himself put it

(#litres_trial_promo) – Christopher stood as MP for Beverley. His election was by no means a foregone conclusion since the rival candidate, Sir James Pennyman, had an enthusiastic following. ‘Sir James came yesterday’ wrote John Hopper, ‘… they all cry Sir James for ever as usual, and the Bells Ringing with Every Demonstration of Joy at seeing him’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is a measure of Christopher’s own popularity that he was returned with a majority of thirty-three, inspiring a local poet, John Bayley of Middleton, to come up with a suitably unctuous set of lines:

Whilst through the Streets loud Acclamations rung,

And Sykes’s Praises dwelt on every Tongue,

‘Twas you whose Merits influenced each Voice,

Unanimous to make so wise a choice.

(#litres_trial_promo)

‘I … heartily congratulate you on your Success,’ wrote Henry Maister, ‘ ’tho I lament the furor of the times which call’d you forth, & only hope you may have no cause to regret the necessity of attending the House which I am sure will not agree with your Constitution, if the Hours in future are too as late as heretofore.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He was sworn in on 20 May, and in the early summer he was summoned to Downing Street – ‘14 at table’ he noted in his diary – where Pitt expressed his gratitude both to him and to his fellow MP, William Wilberforce, for the success of the important Yorkshire vote. Ironically it was the defeated Fox who had said in the past ‘Yorkshire and Middlesex between them make up all England.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

While Christopher voted, there were the first stirrings at Sledmere of a move to improve the old house. On 29 June, 1784, ‘Lady S. laid foundation stone of offices in Court Yard,’

(#litres_trial_promo) noted Christopher in his diary. The work in question was the enlargement and modernisation of the probably rather cramped domestic offices at the north side of the house. The work was especially important as, according to a letter written in September, 1784 by a Miss JC to her sister Nancy, Mrs Marriott, Christopher and Bessy were already entertaining. She attended a small family party, consisting of the Sykeses and their five children, Mr and Mrs Egerton, Bessy’s brother and sister-in-law, and Richard Beaumont, Christopher’s West Yorkshire neighbour, whom she described as a ‘pretty little upright Man of Brazen Nose with a great deal of Linnen about his Neck … a strange being indeed.’ ‘I thought to captivate him,’ she added, ‘but he does not suit my taste.’

JC stayed the better part of a fortnight, and her letter gives a hint of what the atmosphere of the old house was like. ‘ ’Tis now a very good one of its Age,’ she wrote, ‘& reminds me of the Highgate House below stairs – here’s plenty of Books, Pictures good & Antiques, which keep one in constant amusement, besides Organ, Harpsichord, etc. etc.; which strange to tell I’ve exercised my small skill upon, before all the Party every day.’ Though she said she had been ‘taught to dread these Wolds’, she found herself ‘highly delighted & well may; nothing can be finer than the pure air here, only eighteen miles from Bridlington, the beautiful hill & dale of the country makes charming rides etc. Sir C has form’d & is forming great designs in the planting way which will beautify it prodigiously.’ She also confirmed that ‘the house is to be transformed some time’. Of her hosts she wrote, ‘Sir C & Ly Sykes are both extremely obliging, indeed I don’t know in what Family so nearly strangers to me, I cd. have been so agreeably placed for a visit … & not tire of it I assure you. Lady Sykes is very kind yet you must not expect any great polish in her, a resident in the country always, and without Education suitable to her great Fortune but she’ll improve in Londres.’

(#litres_trial_promo) She had, she added, ‘very weak nerves’, and ‘dreads being presented at Court, w’ch you can pity her for: but the family must be elevated’.

(#litres_trial_promo)