По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

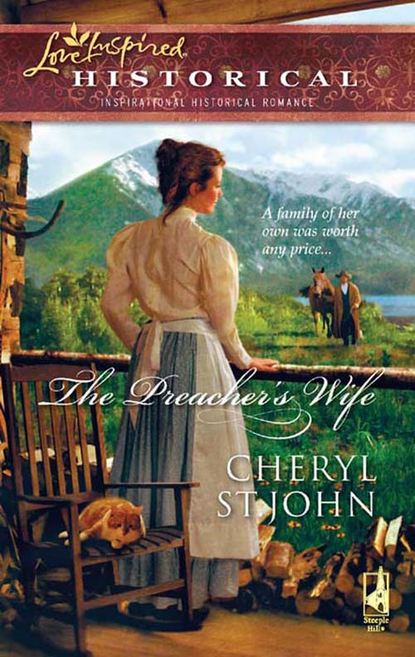

The Preacher's Wife

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You said exactly the right things,” she assured him. “And you’re there for them, that’s what’s important. When they need you, you’re there.”

“It doesn’t seem like enough.”

“We’re never enough in our own ability,” she assured him. “When we acknowledge that is when God works through us. And He worked through you in there.”

He turned his face aside, and his voice was thick when he said, “Thank you.”

She gathered her hem and moved toward the stairs.

Sam watched her leave, his thoughts a little less confusing than they’d been for some time. He recalled what she’d said about not believing in coincidence. It was no accident that his family was staying in this house. He’d been desperate, thinking he was unable to help his daughters. He’d prayed for guidance, for wisdom, for the weight of the burden to be lifted.

And now, for the first time in months, Sam didn’t feel quite so alone.

Josie took the hot iron from the stove and pressed the wrinkles from a pair of plain white pillowcases. The previous evening had been on her mind all morning. A girl as young and sweet as Abigail shouldn’t have nightmares. Her terror had stricken fear into Anna, as well. But their anguish was understandable, considering all they’d gone through.

While it was difficult to observe the younger girls’ misery, Elisabeth’s detachment from the episode was what bothered Josie the most. Elisabeth had watched her sisters until meeting Josie’s gaze, and then she’d turned away—as though unwilling to admit any part in it or to show her feelings. Josie folded the pillowcases and glanced over at Abigail, who was sitting at the table reading a book. Anna was probably cat-watching, and unless her father was present, Elisabeth spent most of her time upstairs.

“What are you reading?” Josie asked.

The girl marked her place with an index finger and looked up. “It’s a story about a boy growing up on a farm. Farms sound like great fun. Have you ever lived on one?”

“No, but I’ve visited quite a few. We’re in the middle of farm country.”

“Maybe we could go see.”

“A lot of the members of our congregation are farmers. If you went along with your father when he makes his calls, you’d get to see where they live.”

“Really?” Abigail looked excited for a moment, but then her expression changed. “Elisabeth joins Papa when he goes calling. Unless there’s school, of course. Do you suppose she saw a farm yesterday?”

Was Abigail feeling unwelcome? “She may have.”

Abigail slid a delicate, tatted marker in the shape of a cross between the pages and closed her book. “I’m gonna go ask her.” She scampered up the stairs.

A knock sounded on the back door, and Josie set the iron on the stove to see who was calling. Grace Hulbert stood holding what appeared to be a pie covered with a dish towel.

“Come in,” Josie greeted her. “The reverend’s in the parlor.”

“I brought an apple pie for the traveling preacher and his family,” Grace told her, peeling back the fabric to reveal a golden-brown crust with a perfectly crimped edge. “Is he here? The preacher man?”

“No, he’s out.”

“Is it true he’s a widower?”

“Sadly so. His wife drowned.” Josie took the pie and set it inside the tin-fronted safe.

“They say he wears a holster and a gun about town. Is it so?”

Josie wondered where that question had come from. “I’m certain everyone on their wagon train needed a gun to protect themselves—and to hunt. Is that so unusual?”

“It’s unusual for a man of the cloth. Has he shot anyone?”

“I have no idea, Grace. What kind of question is that?”

Grace pinched off her white gloves one finger at a time. “He’s the latest bachelor in town, so of course there’s speculation.”

“Bachelor?” Josie’s temperature rose a degree. Grace was a married woman, but she had a daughter who’d been on the shelf since her fiancé ran off six months ago. Josie leveled her gaze on the woman. “Would you like to visit with Reverend Martin? He’s in the parlor.”

“Oh, no.” She had one glove off and stopped removing the other. “I have to run. I just wanted to leave the pie.”

“I’ll let Reverend Martin know you were here.”

Grace headed for the door, but Anna appeared just then. “May I help with the ironing?”

“Is this one of the traveling preacher’s daughters?” Grace asked, turning back.

“This is Anna. Anna, Mrs. Hulbert.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Hulbert,” she said shyly.

“I do quite well, thank you, Anna. It’s a pleasure to meet you. You’re sure a pretty little thing. Do you take after your father?”

Anna moved to stand beside Josie and seemed disinclined to respond.

“You can sprinkle the sheets to dampen them while I see Mrs. Hulbert out,” Josie told her. “Then we’ll figure out what to fix for lunch.”

Grace didn’t give her a chance to move to the door. “I’ll be going.”

She let herself out and the door clicked shut. Josie stared at it for a moment, absorbing that odd exchange. The women of Durham were looking upon Samuel Hart as a bachelor? She tried to shake off the disgust that knowledge made her feel.

Anna was gazing up at her with a curious wrinkle in her brow. “Do I take after my Papa?”

Josie took a sheet from the basket. “Of the three of you, your eyes are most like his. Yours lend themselves to green sometimes, though. Like today, in that pretty green calico dress.”

Anna looked down and wrinkled her freckled nose. “This old thing was Abby’s.”

“You’re fortunate to have sisters who wore such nice clothing and took good care of it.”

The child cocked her head. “Papa says some little girls don’t have nice dresses at all, and they would love to have hand-me-downs.”

“Your papa’s right.”

“He says it’s foolish to buy new dresses, when we already have perfectly good ones that fit me soon enough.”

Josie understood the practicality of reusing their clothing, but she also knew the pleasure of having a new dress. “Surely you’ve had a new dress.”

“I get one for my birthday every year. And one when school starts. But people saw Abigail wear all these other ones.”

“You won’t have that problem now, will you?” she asked. “You’re meeting all new people, and they won’t know someone wore that dress before you.”