По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

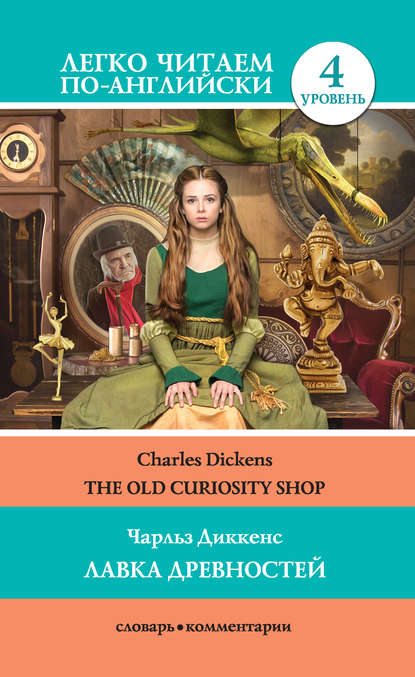

The Old Curiosity Shop / Лавка древностей

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In a few moments Mr. Quilp returned.

“She’s tired, you see, Mrs. Quilp,” said the dwarf. “It’s a long way from her home to the wharf. Poor Nell! But wait, and dine with Mrs. Quilp and me.”

“I have been away too long, sir, already,” returned Nell, drying her eyes.

“Well,” said Mr. Quilp, “if you will go, you will, Nelly. Here’s the note. It’s only to say that I shall see him tomorrow, or maybe next day. Good-bye, Nelly. Here, you sir; take care of her, do you hear?”

Kit made no reply, and turned about and followed his young mistress.

7

Nelly feebly described the sadness and sorrow of her thoughts. The pressure of some hidden grief burdened her grandfather.

One night, the third after Nelly’s interview with Mrs. Quilp, the old man said he would not leave home.

“Two days,” he said, “two whole, clear, days have passed, and there is no reply. What did he tell thee, Nell?”

“Exactly what I told you, dear grandfather, indeed.”

“True,” said the old man, faintly. “Yes. But tell me again, Nell. What was it that he told you? Nothing more than that he would see me tomorrow or next day? That was in the note.”

“Nothing more,” said the child. “Shall I go to him again tomorrow, dear grandfather? Very early? I will be there and back, before breakfast.”

The old man shook his head, and sighing mournfully, drew her towards him.

“It would be of no use, my dear.”

The old man covered his face with his hands, and hid it in the pillow of the couch on which he lay.

8

Mr. Daniel Quilp entered unseen when the child first placed herself at the old man’s side, and stood looking on with his accustomed grin. He soon cast his eyes upon a chair, into which he skipped. Here, then, he sat, one leg cocked carelessly over the other, his head turned a little on one side, and his ugly features twisted into a complacent grimace.

At length, the old man pronounced his name, and inquired how he came there.

“Through the door,” said Quilp pointing over his shoulder with his thumb. “I’m not quite small enough to get through key-holes. I wish I was. I want to have some talk with you, particularly, and in private. With nobody present, neighbour. Good-bye, little Nelly.”

Nell looked at the old man, who nodded to her to retire, and kissed her cheek.

“Ah!” said the dwarf, smacking his lips, “what a nice kiss! What a capital kiss!”

Nell went away.

“Tell me,” said the old man, “have you brought me any money?”

“No!” returned Quilp.

“Then,” said the old man, clenching his hands desperately, and looking upward, “the child and I are lost!”

“Neighbour,” said Quilp, “let me be plain with you. You have no secret from me now.”

The old man looked up, trembling.

“You are surprised,” said Quilp. “Well, perhaps that’s natural. You have no secret from me now, I say; no, not one. For now, I know, that all those sums of money, that all those loans, advances, and supplies that you have had from me, have gone… shall I say the word?”

“Yes!” replied the old man, “say it, if you will.”

“To the gaming-table,” rejoined Quilp, “This was your precious plan to become rich; this was the secret certain source of wealth in which I spent my money; this was your inexhaustible mine of gold, your El Dorado[26 - El Dorado – Эльдорадо], eh?”

“Yes,” cried the old man, “it was. It is. It will be, till I die.”

“I have been blinded,” said Quilp looking contemptuously at him, “by a mere shallow gambler!”

“I am no gambler,” cried the old man fiercely. “I never played for gain of mine, or love of play. Every piece I staked, I whispered to myself that orphan’s name and called on Heaven to bless the venture; which it never did. Who were those with whom I played? Men who lived by plunder, profligacy, and riot.”

“When did you first begin this mad career?” asked Quilp.

“When did I first begin?” he rejoined, passing his hand across his brow. “When was it, that I first began? When I began to think how little I had saved, how long a time it took to save at all.”

“You lost your money, first, and then came to me. While I thought you were making your fortune (as you said you were) you were making yourself a beggar, eh? Dear me!” said Quilp. “But did you never win?”

“Never!” groaned the old man. “Never won back my loss.”

“I thought,” sneered the dwarf, “that if a man played long enough he was sure to win.”

“And so he is,” cried the old man, “so he is; I have always known it. Quilp, I have dreamed, three nights, of winning the same large sum, I never could dream that dream before, though I have often tried. Do not desert me, now I have this chance. I have no resource but you, give me some help, let me try this one last hope.”

The dwarf shrugged his shoulders and shook his head.

“See Quilp, good tender-hearted Quilp,” said the old man, drawing some papers from his pocket with a trembling hand, and clasping the dwarfs arm, “only see here. Look at these figures, the result of long calculation, and painful and hard experience. I must win. I only want a little help once more, a few pounds, dear Quilp.”

“The last advance was seventy,” said the dwarf; “and it went in one night.”

“I know it did,” answered the old man, “but that was the worst night of all. Quilp, consider, consider that orphan child! Help me for her sake, I implore you; not for mine; for hers!”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t do it really,” said Quilp with unusual politeness. “I’d have advanced you, even now, what you want, on your simple note of hand, if I hadn’t unexpectedly known your secret way of life.”

“Who told you?” retorted the old man desperately, “Come. Let me know the name the person.”

The crafty dwarf said, “Now, who do you think?”

“It was Kit, it is the boy; he is the spy!” said the old man.

“Yes, you’re right” said the dwarf. “Yes, it was Kit. Poor Kit!”

So saying, he nodded in a friendly manner, and left, grinning with extraordinary delight.

“Poor Kit!” muttered Quilp. “I think it was Kit who said I was an uglier dwarf than could be seen anywhere for a penny, wasn’t it? Ha ha ha! Poor Kit!”

“She’s tired, you see, Mrs. Quilp,” said the dwarf. “It’s a long way from her home to the wharf. Poor Nell! But wait, and dine with Mrs. Quilp and me.”

“I have been away too long, sir, already,” returned Nell, drying her eyes.

“Well,” said Mr. Quilp, “if you will go, you will, Nelly. Here’s the note. It’s only to say that I shall see him tomorrow, or maybe next day. Good-bye, Nelly. Here, you sir; take care of her, do you hear?”

Kit made no reply, and turned about and followed his young mistress.

7

Nelly feebly described the sadness and sorrow of her thoughts. The pressure of some hidden grief burdened her grandfather.

One night, the third after Nelly’s interview with Mrs. Quilp, the old man said he would not leave home.

“Two days,” he said, “two whole, clear, days have passed, and there is no reply. What did he tell thee, Nell?”

“Exactly what I told you, dear grandfather, indeed.”

“True,” said the old man, faintly. “Yes. But tell me again, Nell. What was it that he told you? Nothing more than that he would see me tomorrow or next day? That was in the note.”

“Nothing more,” said the child. “Shall I go to him again tomorrow, dear grandfather? Very early? I will be there and back, before breakfast.”

The old man shook his head, and sighing mournfully, drew her towards him.

“It would be of no use, my dear.”

The old man covered his face with his hands, and hid it in the pillow of the couch on which he lay.

8

Mr. Daniel Quilp entered unseen when the child first placed herself at the old man’s side, and stood looking on with his accustomed grin. He soon cast his eyes upon a chair, into which he skipped. Here, then, he sat, one leg cocked carelessly over the other, his head turned a little on one side, and his ugly features twisted into a complacent grimace.

At length, the old man pronounced his name, and inquired how he came there.

“Through the door,” said Quilp pointing over his shoulder with his thumb. “I’m not quite small enough to get through key-holes. I wish I was. I want to have some talk with you, particularly, and in private. With nobody present, neighbour. Good-bye, little Nelly.”

Nell looked at the old man, who nodded to her to retire, and kissed her cheek.

“Ah!” said the dwarf, smacking his lips, “what a nice kiss! What a capital kiss!”

Nell went away.

“Tell me,” said the old man, “have you brought me any money?”

“No!” returned Quilp.

“Then,” said the old man, clenching his hands desperately, and looking upward, “the child and I are lost!”

“Neighbour,” said Quilp, “let me be plain with you. You have no secret from me now.”

The old man looked up, trembling.

“You are surprised,” said Quilp. “Well, perhaps that’s natural. You have no secret from me now, I say; no, not one. For now, I know, that all those sums of money, that all those loans, advances, and supplies that you have had from me, have gone… shall I say the word?”

“Yes!” replied the old man, “say it, if you will.”

“To the gaming-table,” rejoined Quilp, “This was your precious plan to become rich; this was the secret certain source of wealth in which I spent my money; this was your inexhaustible mine of gold, your El Dorado[26 - El Dorado – Эльдорадо], eh?”

“Yes,” cried the old man, “it was. It is. It will be, till I die.”

“I have been blinded,” said Quilp looking contemptuously at him, “by a mere shallow gambler!”

“I am no gambler,” cried the old man fiercely. “I never played for gain of mine, or love of play. Every piece I staked, I whispered to myself that orphan’s name and called on Heaven to bless the venture; which it never did. Who were those with whom I played? Men who lived by plunder, profligacy, and riot.”

“When did you first begin this mad career?” asked Quilp.

“When did I first begin?” he rejoined, passing his hand across his brow. “When was it, that I first began? When I began to think how little I had saved, how long a time it took to save at all.”

“You lost your money, first, and then came to me. While I thought you were making your fortune (as you said you were) you were making yourself a beggar, eh? Dear me!” said Quilp. “But did you never win?”

“Never!” groaned the old man. “Never won back my loss.”

“I thought,” sneered the dwarf, “that if a man played long enough he was sure to win.”

“And so he is,” cried the old man, “so he is; I have always known it. Quilp, I have dreamed, three nights, of winning the same large sum, I never could dream that dream before, though I have often tried. Do not desert me, now I have this chance. I have no resource but you, give me some help, let me try this one last hope.”

The dwarf shrugged his shoulders and shook his head.

“See Quilp, good tender-hearted Quilp,” said the old man, drawing some papers from his pocket with a trembling hand, and clasping the dwarfs arm, “only see here. Look at these figures, the result of long calculation, and painful and hard experience. I must win. I only want a little help once more, a few pounds, dear Quilp.”

“The last advance was seventy,” said the dwarf; “and it went in one night.”

“I know it did,” answered the old man, “but that was the worst night of all. Quilp, consider, consider that orphan child! Help me for her sake, I implore you; not for mine; for hers!”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t do it really,” said Quilp with unusual politeness. “I’d have advanced you, even now, what you want, on your simple note of hand, if I hadn’t unexpectedly known your secret way of life.”

“Who told you?” retorted the old man desperately, “Come. Let me know the name the person.”

The crafty dwarf said, “Now, who do you think?”

“It was Kit, it is the boy; he is the spy!” said the old man.

“Yes, you’re right” said the dwarf. “Yes, it was Kit. Poor Kit!”

So saying, he nodded in a friendly manner, and left, grinning with extraordinary delight.

“Poor Kit!” muttered Quilp. “I think it was Kit who said I was an uglier dwarf than could be seen anywhere for a penny, wasn’t it? Ha ha ha! Poor Kit!”