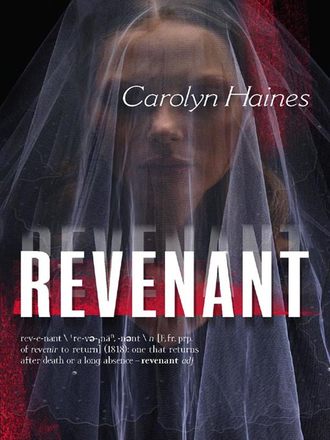

Revenant

Deputy Warden Vance took me into an office where Alvin waited. He’d been in prison since he was convicted in 1983, more than twenty years ago. In the interim he’d lost his hair, his color, his vision and his body. He was a small, round dumpling of a man with a doughy complexion and Coke-bottle glasses. He sat behind a desk piled with papers. Two flies buzzed incessantly around him.

“I’ve read some of your articles in the Miami paper,” he said as I sat down across from him. “I’m flattered that such a star is interested in talking to me.”

“What do you know about the five bodies buried in the parking lot of your club?” I asked.

“Mitch Rayburn asked the same thing. Yesterday. You know I remember giving a check to an organization that helped put Mitch through law school. Isn’t that funny?”

Alvin’s eyes were distorted behind his glasses, giving him an unfocused look. I knew the stories about Alvin. It was said he liked to look at the people he hurt. Rocco was the exception.

“Mitch had a hard time of it, you know,” he continued, as if we were two old neighbors chewing the juicy fat of someone else’s misfortune. “He was just a kid when his folks died. They burned to death.” He watched me closely. “Then his brother drowned. I’d say if that boy didn’t have bad luck, he’d have no luck at all.” He laughed softly.

My impulse was to punch him, to split his pasty lips with his own teeth. “I found the building permits where a room was added to the Gold Rush in October of 1981,” I said instead. “The bodies were there before that. Sometime that summer. Do you remember any digging in the parking lot prior to the paving?”

“Mitch told me that it was the same summer all of those girls went missing,” Alvin said. “He believes those girls were buried in my parking lot after they were killed. Imagine that, those young girls lying dead there all these years.”

“Do you know anything about that?”

“No, I’m sorry to say I don’t. My involvement with girls was generally giving them a job in one of my clubs. It’s hard to get a dead girl to dance.” He laughed louder this time.

“Mr. Orley, I don’t believe that someone managed to get five bodies in the parking lot of your club without you noticing anything.” I tapped my pen on my notebook. “I was led to believe that you aren’t a stupid man.”

“I’m far too smart to let a has-been reporter bait me.” He laced his fingers across his stomach.

“You never noticed that someone had been digging in your parking lot?”

“Ms. Lynch, as I recall, we had to relay the sewage lines that year. Construction equipment everywhere, with the paving. I normally didn’t go to the Gold Rush until eight or nine o’clock in the evening. I left before dawn. I wasn’t in the habit of inspecting my parking lot. I paid off-duty police officers to patrol the lot, see unattended girls to their cars, that kind of thing. I had no reason to concern myself.”

“How would someone bury bodies there without being seen?”

“Back in the ’80s there were trees in the lot. The north portion was mostly a jungle. There was also an old outbuilding where we kept spare chairs and tables. If the bodies were buried on the north side of that, no one would be likely to see them. Mitch didn’t tell me exactly where the bodies were found.”

I wondered why not, but I didn’t volunteer the information. “The killer would have had to go back to that place at least five times. That’s risky.”

Orley shrugged. “Maybe not. On weeknights, things were pretty quiet at the Gold Rush, unless we had some of those girls from New Orleans coming in. Professional dancers, you know. Then—” he nodded, his lower lip protruding “—business was brisk. Especially if we had some of those fancy light-skinned Nigras.”

Alvin Orley made my skin crawl. “Do you remember seeing anyone hanging around the club that summer?”

“Hell, on busy nights there would be two hundred people in there. And if you want strange, just check out cokeheads and speed freaks, mostly little rich boys spending their daddy’s money. The lower-class customers were more interested in weed. If I kept a book of my customers, you’d have some mighty interesting reading.”

He was baiting me. “I’m sure, but since you have no evidence of these transactions, it would merely be gossip. I’m not interested in uncorroborated gossip.”

“But your publisher is.” He wheezed with amusement. “There was a man, now that I think about it. He was one of those Keesler fellows. Military posture, developed arms. He was in the club more than once that summer.”

“Did you ever mention it to the police?”

Orley laughed out loud, his belly and jowls shaking. “You think I just called them up and told them someone suspicious was hanging around in my club, would they please come right on down and investigate?”

Blood rushed into my cheeks. “Do you remember this man’s name?”

“We weren’t formally introduced.”

“I have some photographs of the young ladies who went missing that summer. Would you look at them and see if any are familiar?” I pulled them from my pocket and pushed them across the desk to him.

He stared at them, pointing to Maria Lopez. “Maybe her. Seems like I saw her at the club a time or two. I always had a yen for those hot-blooded spics.” He licked his lips and left a slimy sheen of saliva around his mouth. “Nobody gives head like a Spic.”

“Maria Lopez was sixteen.”

“Maybe her mother should’ve kept a closer eye on her and kept her at home.”

“Any of the others?” I asked.

He looked at them and shook his head. “I can’t really say. Back in the ’80s, the Gold Rush did a lot of business on the weekends. College girls looking for a good time, Back Bay girls looking for a husband, secretaries. They all came for the party.”

I stood up. “Why did you decide to pave the parking lot, Mr. Orley?” I asked.

“It was shell at the time. I was going to reshell it, but the price had gone up so much that I decided just to pave it.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“Be sure and come back, Ms. Lynch. I find your questions very stimulating.”

He was chuckling as I walked out in the hall where a guard was waiting. Alvin Orley’s conversation was troubling. If the parking lot was shell, it would have been obvious that someone had dug in it. Orley wasn’t blind, and he wasn’t stupid.

Once the prison was behind me, I tried to focus on the beauty of the day. Pale light with a greenish cast gave the trees a look of youth and promise. I stopped in St. Francisville for a late lunch at a small restaurant in one of the old plantations. It was a lovely place, surrounded by huge oaks draped with Spanish moss. Sunlight dappled the ground as it filtered through the live oak leaves, and the scent of early wisteria floated on the gentle breeze.

I was seated at one of several tables set up on a glassed-in front porch. I ordered iced tea and a salad. The accents of four women seated at a table beside me were pleasantly Southern. They talked of their husbands and homes. I glanced at them and saw they were about my age, but beautifully made up and dressed with care. Manicured fingernails flicked on expressive hands. Once, I’d polished my nails and streaked my dark blond hair with lighter strands.

“Oh, here comes Cornelia,” one woman exclaimed to a chorus of “Isn’t she lovely?”

I looked out the window and my heart stopped with screeching pain. A young girl with flowing dark hair skipped up the sidewalk. She wore blue jeans and a red shirt. For just one second, I thought it was Annabelle. My brain knew better, but my heart, that foolish organ, believed. I half rose from my chair. My hands reached out to the girl, who hadn’t noticed me.

The women beside me hushed. A fork clattered onto a plate. A woman got up and ran to the door as the young girl entered. She pulled her to her side and steered her away from me as she returned to her table.

I sat down, waited for my lungs to fill again, my heart to beat. When I thought I could walk, I left money on the table and fled.

I drove for a while, trying not to think or feel. At three o’clock I had no choice but to pull over, find a pay phone—because reception was too aggravating on my cell—and dictate my story back to the newspaper. Jack volunteered to take the dictation, and I was glad.

“I’ve got about thirty inches on Alvin Orley’s illegal activities,” he said as he waited for me to think a minute. “I even got an interview with one of his old dancers. She said most all of them had to have sex with him to keep their jobs.”

I gave him my story, the gist of which was that Alvin failed to notice his parking lot was dug up. It wasn’t much of a story, but it would be enough for Brandon.

“Hey, kid, are you okay?” Jack asked.

“Tell me about the fire that killed Mitch’s parents.”

“I forget that you didn’t grow up around here. I guess I remember it so well because at first blush everyone thought it was arson. Harry Rayburn was a prominent local attorney who defended a lot of scum. Everyone jumped to the conclusion that an unhappy client had set the fire.”

“It was an accident?”

“That’s right. Electrical.”

“Both parents died, but the boys escaped?”

“Mitch was just a kid, and he was on a Boy Scout campout. Jeffrey was at baseball camp at Mississippi State University. He was still in high school but scouts were already looking at him. From everything I heard, it was a real tragedy. The Rayburns were sort of a Beaver Cleaver family. Mrs. Rayburn was a stay-at-home mom.” He sighed. “The house went up like a torch.” He hesitated. “Sorry, Carson.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “I asked.”

“I covered it for the paper, and I was there when Jeffrey got home from State. He’d picked Mitch up at Camp DeSoto along the way. It broke my heart to see those boys standing by the smoking ruins of what had been their home.”

“You’re positive there was no sign of arson?” I could have read Alvin Orley wrong, but I thought he’d hinted that Mitch’s luck was bad for a reason.

“None. That fire was examined with a fine-tooth comb. It was accidental.”

“I’m headed back to Ocean Springs. Tell Hank to call me on my cell if he needs me.”

“Will do, Carson. Drive carefully.”

I was tempted to get off the interstate at Covington and revisit some of my old haunts. Dorry and I had both shown hunter-jumper. Covington, Louisiana, had hosted some of the finest shows of the local circuit. Dorry had always been the better rider; she rode for the gold. I was more timid, more worried about my horse. I smiled at the full-blown memory of both my admiration for, and my jealousy of, her.

When I went to visit my parents, I’d be able to see Mariah and Hooligan, our two horses, as well as Bilbo, the pony. Both horses were close to thirty now, but they were in good shape. Dad took excellent care of them, and Dorry’s daughter, Emily, groomed and exercised them. She was the only one of Dorry’s children who liked animals, and truthfully, the only one that I felt any kinship with. At twelve, she was only a year older than Annabelle would have been. Had we lived close together, I believed they would have been famous friends.

I checked my watch and stayed on the interstate. I’d spent enough time on memory lane. I needed to get back to Ocean Springs. There were a few loose ends I wanted to tie up before the weekend, and Mitch Rayburn was one of them. He’d promised to call. There was also the matter of the four missing girls. I’d have to run their names in Sunday’s paper, but it would look better for everyone if I could quote Mitch or Avery. I wrote leads in my head as I sped down the highway toward home.

Dark had fallen by the time I pulled into my driveway. My headlights illuminated the shells that served as paving. If someone buried even a rabbit under the shells, I’d notice that they’d been disturbed. Much less five human bodies. Alvin Orley was either blind or lying, and I was willing to bet on the latter.

The cats were glad to see me. The truth was, Daniel would have made a better home for them. It was my selfishness at wanting to cling to that last little piece of my daughter that had made me insist on keeping them. I fed them, and somewhat mollified, Vesta settled on my lap as I went through my phone messages. My mother had called twice, Dorry once, Daniel once and Mitch Rayburn once. I called Mitch back.

“We got a positive identification on the bodies. Or at least four of them. You were right, Carson.”

I took no pleasure in that. “We’ll run the story Sunday. Any idea who the fifth body might be?”

“Not yet. Did Orley tell you anything?”

“I didn’t find out squat except that Alvin Orley belongs in prison. He’s a vile man.”

“He still manipulates from behind prison bars,” Mitch cautioned. “He’s not a man to piss off.”

“Don’t worry, I try to keep my personal opinion out of print.”

He laughed. “Brandon must be bitterly disappointed.”

Mitch knew Brandon well, yet he didn’t let it bother him. “Did you find any leads to the girls’ killer?”

“The missing fingers. The hair combs. We have leads we’re pursuing.”

“I wonder why he stopped killing.”

Mitch hesitated. “That’s a good question. Maybe he moved on, found a new location.”

“Have you checked the MO with other locations?”

“Nothing so far, but this was twenty-odd years ago.” He sighed. “I’m going to go for a jog and hope that self-abuse will shake something loose in my brain.”

“Sweat some for me,” I said. “I’m going to listen to some country music and drink something with ice and olives in it.”

“You’re too classy for me, Carson,” he said, laughing as he hung up.

5

I took a long, hot bath, eventually realizing that I couldn’t scrub Alvin Orley off my skin or out of my consciousness. Contamination by proximity. He was like a virus, a nasty one. I dressed, opened a can of soup for dinner, then headed for the public beach.

In truth, it wasn’t much of a beach, just the eastern shore of the Bay of Biloxi. Front Beach Drive curved along the water, the homes of the wealthy perched like dignified old guards upon the embankment. Many were set back off the road, telling of a time when lawns were purchased with playing fields for children in mind. Huge oaks shaded the houses and the road. It was early for a Friday night, and the road was quiet. The city had cracked down on the teenagers who liked to park and party there. To the north, it was cocktail hour at the Oceans Springs Yacht Club, a Jim Walters-looking building on stilts. To the south, the water undulated to the Mississippi Sound, passed between Horn and Ship Islands and finally mingled with the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

I sat on a low stone wall and listened to the shush of the water. Instead of being comforting, it was unsettling, and I took off my shoes and walked in the cold sand. March was warm enough to tempt the flowers out, but the wind off the water at night was still cool. The stars on this stretch of beach, undimmed by competition with the casinos, were brilliant. I walked for an hour, then got in my truck and headed for Highway 57 and the lonely road to Lissa’s Lounge, a honky-tonk of the old school.

When I was a child, the only points of interest along the highway had been a bridge over Bluff Creek where teenagers swam on hot summer days, the Home of Grace for alcoholic men and Dees General Store. Until the past ten years, most of the land in north Jackson County had been owned by the paper companies. Now there were subdivisions cropping up everywhere. The huge tracts of timber had been clear-cut one final time and sold to developers. Horseshoe-shaped subdivisions with names like Willow Bend and Shady Lane jutted up on treeless lots.

Along the interstate, a large tract of land had been claimed to preserve the sandhill crane, a prehistoric-looking bird that was near extinction. The rednecks resented the no-hunting rule in the preserve, so they regularly set fire to it. So far, the score was 2-0 in the birds’ favor. Last fall, two arsonists had drunk a bottle of Early Times and set a hot fire that swept out of control. They watched the blaze begin to chew through the woods and thought it was great fun, until the wind changed. Sayonara, motherfuckers.

Lissa’s was tucked back off the highway on Jim Ramsey Road. It was an old place where folks had come to dance and drink for decades. Lissa Albritton was in her sixties, but she didn’t look a day over forty-nine. She was at the door every Friday night taking a three-dollar cover charge and checking the men’s asses when they walked by. She was a connoisseur. “That man sure knows how to pack out some denim,” she’d say when she saw something that caught her fancy. If the man walked by close enough, she’d cop a feel.

There were plenty of classier bars in Ocean Springs and along the Gulf Coast, places where women wore black sheaths and pearls and men wore pinstripes and ties. The coast had a highly developed sheen of sophistication these days. That’s why I preferred Lissa’s.

The karaoke duo, the Bad Boys, was rocking the bar by the time I got there. They were twin brothers, Larry and Leon, in their fifties with professional voices and day jobs as mechanics.

Lissa waved me in. “No charge, Carson. They’ve been waiting for you.” Her blond hair was swept up and sprayed so righteously that not a strand dared to wilt. I pushed through the door and disappeared in a haze of cigarette smoke.

“Hey, Carson,” the bartender called out as I made my way to the bar. “Leon’s been looking for you. He has some requests for ‘Satin Sheets.’” He handed me a martini and a wink. “This one’s on me. You should have been a queen of country. Like Jeanne Pruette.”

Kip was a good guy and a primo bartender. Lissa knew his value and paid him well. I took my drink and found a table against the wall, letting the smoke and darkness fall over me like a cloak. I found a crushed pack of Marlboros in my purse and lit one. It was Friday night, my weekly nod to another of my vices.

The patrons at Lissa’s were evenly split between men and women. Everyone wore jeans. The thinner women wore tight shirts, often with some decorative cutout that strategically revealed an asset. The older, heavier women wore the same thing with a much different effect. The men were lean and muscular and often silent. They drank hard, danced hard and worked hard. I was willing to bet not a single one of them failed to sleep hard when they finally clocked out. I envied them that.

“Carson Lynch, report to the microphone.”

I finished my drink, signaled for another and went to the stage. Leon handed me the mike. “Satin Sheets” was an old classic, a song of too much money and not enough love. It wasn’t my theme song, but I admired the crafting. I sang it with heart, and when I got back to my table, there were two martinis waiting on me.

Leon sang a waltz and then a two-step and I watched the dancers. One middle-aged couple quartered the dance floor, each move synchronized. They stared into each other’s eyes as if no one else existed. I smoked another cigarette and sang “Take the Ribbon from My Hair” when Larry motioned me back to the stage.

Instead of a drink, there was a note at my table. “You’re four up in the credit department.” I smiled at Kip. He knew I had a long drive home.

“Care to dance?”

The man was tall and handsome. He wore a black cowboy hat and he had the confidence of that breed.

“I don’t dance,” I said.

“I can teach you.”

“Another time, maybe.” Dancing was part of another lifetime.

He put his hand on a chair. “Mind if I sit?”

I did and I didn’t. I liked men. I enjoyed talking with them, laughing with them. I especially liked confident men; they had the balls to charm. But it always came down to expectations, and I was always a disappointment.

“You can sit down, but I’m not dancing and I’m not going home with you.”

He smiled. “You sure I was going to ask?”

“No. I just don’t want a misunderstanding when liquor has clouded your memory or your judgment.”

We talked while I sipped my martinis and smoked three more cigarettes. His name was Sam Jackson, and he ran cows and grew hay above Saucier.

“I’ll bet you’re the only woman in here drinking a martini,” he said, sipping a Miller Lite. “You don’t really belong here.”

“I don’t really belong anywhere.” I ate the last olive.

“You sound like you’re from here, though.” He studied me. “We’ve talked about grass and cows and horses and weather. I don’t know anything about you.”

“I’m a reporter for the Biloxi newspaper.”

He put his beer down. “Working on a story?”

I shook my head. “I like Leon and Larry. I like this place. No one knows me and no one bothers me. Kip makes a martini just the way I like it.”

“I’ll make you a bet,” he said, leaning forward, a hint of a smile in his eyes. “I’ll bet you that eventually you dance with me.”

“How much?” I asked.

“Oh, just one dance,” he said. “Then if I don’t step on your toes, we might try it again.”

I couldn’t help but laugh. “How much do you bet?”

“I’ll bet you a day-long ride on a goin’ little mare when I move the cows in another few weeks.”

“How did you know I rode?” I asked.

“Same way I know you dance,” he said. He pushed back his chair, tipped his hat and left. I watched him for a moment as he was stopped by a redhead and led the way to the dance floor. He swung her into a two-step.

I collected my two remaining cigarettes and left. It was almost midnight. Time to go.

Clouds gathered in the south, and as I reached the truck, they rushed the moon. The night was suddenly black. I was glad for the darkness and the fact that no other cars were on the highway. I’d eaten very little all day, and I realized I was hungry. Carbohydrates. And fat. Maybe a chocolate shake, too. It would help prevent a hangover tomorrow. I drove over the Biloxi Bridge toward the glowing neon of gambler’s paradise. There was a Wendy’s that stayed open late.

I’d just picked up my order of a burger, fries and a shake when I heard the sirens. There were 137 law officers in the Biloxi PD. It sounded as if half of them were traveling at a high rate of speed down Highway 90. Blue lights sped by. I fell in behind them, hoping no one would question a black Ford pickup at the end of a caravan of squad cars.

They pulled into a lot beside the beach where earlier in the day tourists had sunned and swum. A public pier stretched out over the water, disappearing into the night. Police officers jumped from their vehicles and ran on the weathered boards, their footsteps pounding. I followed at a sedate walk. No one stopped me or asked any questions.

The pier was about a hundred yards long and was used primarily for fishing, although I wouldn’t eat anything caught so close to shore. Officers had high-beam flashlights and were searching the old boards. There was something else there, too. I could catch glimpses but not enough to get the whole picture.

“Put someone on the beach,” Avery Boudreaux called out. “Block everyone off. No one comes on this pier, you got it? No one. Particularly no media.”

“Yes, sir,” two officers said and headed in my direction.

I tucked my head and walked past them as if I belonged there. I kept walking. When I was close enough to catch a glimpse in an officer’s light, I stopped. My stomach coiled, threatening revolt. I took a deep breath.

“Shit!” Avery exclaimed as he came to stand beside me. “How in the hell did you get out here?”

“Just lucky, I guess.” My voice strained for control.

He took my elbow and steadied me. “Don’t you dare mess up my crime scene,” he said.

“I won’t,” I promised.

“And don’t go any closer!”

“I won’t.”

“Are you okay?”

I nodded.

“Stay out of the way and don’t move. Mitch will be here any minute. He can take care of you.” He released my arm and went to talk to two officers.

I stared at the dead girl. She slumped on a bench, blood pooling around her hips and slowly dripping onto the pier. She looked as if she was smiling, but it was a trick of death. The rictus of her face was a strange imitation of the slash that had opened her throat.