По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

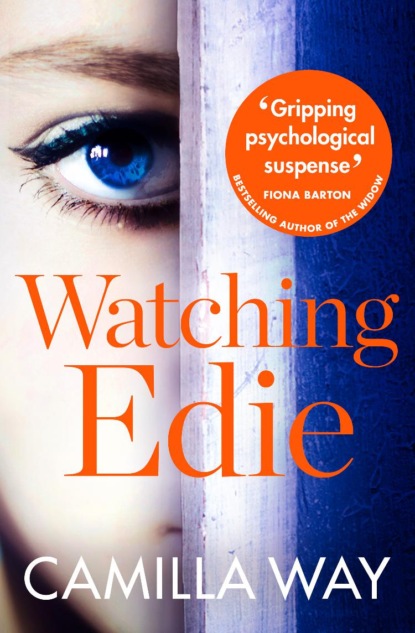

Watching Edie: The most unsettling psychological thriller you’ll read this year

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Amongst the scattered envelopes lies one that’s pink and square. I don’t remember ever seeing Heather’s handwriting before, but I know instinctively that it’s from her. The physical presence of it makes my scalp crawl but I return with it upstairs, carrying it like some dead and rotten thing between my fingertips. There on my kitchen table it sits. I leave it unopened, curling up in a ball on my sofa, my legs tucked beneath me, my arms tight around my bump. The minutes tick by until with quick decisiveness I run into the kitchen, snatch up the envelope and tear it open. Along with a piece of pink notepaper a photograph falls out, landing face down on the floor.

My hands trembling, I pick up the letter and quickly scan the words. Dear Edie, it says.

I’ve tried to phone you loads but I think I’ve got the wrong number. Can I come back and see you? Here’s my number at the top. Please phone me.

Lots of love from Heather Wilcox. XOXO

PS. I found this photo of us! LOL! You can keep it if you want!! X

Eventually, reluctantly, I pick up the picture and look at it. It’s of Heather and me. I’m sitting just in front of her by the quarry and I’m smiling up at the camera, holding my hand out as if to defend myself from its lens, my fingers a big pink blur in the foreground. Heather is looking away, staring off down the hill. I’m shocked at how childish we look, our faces plump and stupid with youth. But the picture’s not of us, not really. Even though he’s the one taking the picture, it’s of Connor. He is in the expression in my eyes and in the shadow that streaks across the grass between Heather and me. Connor. In my flat the walls feel a little closer, the air a little harder to breathe. A wave of nausea hits me and I have to run to the sink to vomit up the bile that floods my mouth.

Opening the kitchen window I crawl out on to the flat roof of the neighbour’s bedsit below, gulping at the fresh air until the sickness begins to pass. Usually I love to sit out here, high above the city spread out before me in all its noisy, dirty glory, comforted by its vastness and indifference. It’s not true what they say about London, that it looks down on the rest of the country – in fact London’s barely aware of the England that lies beyond its borders. In its self-absorbed bubble, towns like Fremton and all they represent barely figure, and that has always suited me just fine.

But now, even as the sickness recedes, I see only Connor’s face, the moment he’d first approached me in the square, and I feel a reflexive cold punch to my guts. I remember how the sight of him had made the rest of the world vanish, how immediate and physical it had all been. I had never seen anyone so beautiful. He’d asked me for a light, in that quiet voice of his that was like cigarettes, like syrup. Then he’d sat down next to me as if he didn’t doubt for a second I’d want him to. I think he asked me what my name was, where I was from. It didn’t matter: all I knew was that I’d never ever seen eyes like his before; never in my life had I seen such beautiful green eyes.

I shudder. Far below me is the building’s communal garden, full of abandoned furniture and bags of rubbish. As I watch, one of the new lads from the ground-floor flat appears with his dog and it squats down next to a fridge freezer while he waits. The boy, about seventeen or so, tall and well built, smokes a cigarette and fiddles idly with his mobile, oblivious to me up here looking down at him. I will be due at the restaurant soon and I need to catch the bus to another seven-hour shift, earning all the money I can before the baby comes. I make myself get up and, resolving to throw the letter and photo in the bin, crawl back through my kitchen window. But at the sight of them lying there on my table I freeze then barely notice as I sink into a chair.

Beyond my window the light begins to change as the afternoon wears on, an ice-cream van’s chimes jangle in the warm, close air, the school-run traffic picks up, slowly, rain begins to fall. But I’m only dimly aware of these things. Despite my best intentions I am entirely back there at the Wrexham quarry, the night before I left for good, memories slamming into me one after another: the confusion and panic, the awful, terrifying screams as everything spiralled out of control. Here in my flat the last seventeen years vanish, meaningless and unreal compared to the tangible, unforgettable horror of that night.

What does Heather want from me now? What could she possibly want from me now?

Heather seems to haunt me in the days and weeks that follow. I imagine I smell her sour, oniony scent wherever I go, I keep glimpsing her from the corner of my eye, or hear her voice amongst others in the street, causing me to turn sharply, seeking her out with a pounding heart, only to find that she isn’t there at all.

When my Uncle Geoff phones one day out of the blue, I’m relieved almost to the point of tears when he tells me he’s coming round, so grateful am I for the distraction. He sits here now, filling my tiny kitchen with his comforting smell of cologne and cigar smoke, his broad Manchester accent familiar and soothing. I feel his eyes on me, watching me fondly as I make him tea, and for the first time since Heather turned up again, I begin to relax.

‘You all right then, Edie love?’ he says.

‘Yeah, you know. Not bad.’

‘Not long till the little one arrives.’

‘No, not long now.’

He takes the tea I offer him and says, ‘Be the making of you, I reckon. You’ll be a great mum, you’ll see.’

I smile back at him, touched. ‘Thanks, Uncle Geoff.’

‘Everything going well with that fella of yours, is it?’

I nod, and we drop each other’s gaze. He knows as well as I do there’s no fella on the scene, but he’s too tactful to say. I’ve always loved that about him, his unquestioning, steady support. I think about how he’d taken me in when I first arrived on his doorstep at seventeen, how kind he’d been to me, and the memory calms me and gives me strength.

When he leaves again a few hours later, I watch him from my window setting off down the street, and my heart tightens with love for him. He’s nearly sixty now and I’d only ever known him as a bachelor, though Mum had told me he’d been married once, years before, to a woman who’d run off and broken his heart. He never speaks about her, but you can somehow see the memory of her there still, in his eyes and his smile, the way they do remain a part of us, those people who have hurt us very deeply, or who we have hurt, never letting us go, not entirely.

Before (#ulink_4e973789-27f2-50e9-8eb4-e86fa687bac1)

In the square, Edie shivers and stands up, squashing with her foot the cigarette she’d been smoking. ‘Where’re you off to?’ she asks, and when I tell her I’m heading home she smiles and says, ‘I’ll walk with you.’ And just like that it’s as though the man, whoever he was and whatever went on between them, is forgotten.

‘Great,’ I say, ‘fantastic!’

She bends to pick up her bag, and as she does her skirt rides up to show her knickers. I quickly look away. ‘GCSE results will be in pretty soon,’ I say hurriedly, as we begin to walk. Her bare arm brushes mine, the fine hairs on both mingling briefly together.

‘Yeah? How do you think you did?’

I shrug. ‘OK, I guess. I was predicted ten As, so …’

She turns to me, wide-eyed. ‘Ten As? Ten As?’ She whistles. ‘Wow, brainbox, huh?’

I glance at her, trying to work out if she’s saying this in the same way Sheridan Alsop would, as though there’s something mystifyingly pathetic about me doing well at school, but then I see her admiring smile and my tummy dips with happiness.

‘God, I wish I was clever,’ she says a few moments later. ‘I did my GCSEs last year. Total disaster! Got to retake some of them while I do my A-levels.’ I notice again how nice her voice is. Loud and clear and confident, her words spilling out quickly in her Manchester accent. She’s delving into her bag and eventually pulls out another cigarette. She lights it, and offers one to me. ‘No?’ she says, when I shake my head. ‘Very wise. Wish I’d never started.’ She laughs, a lovely, warm throaty sound, and says, ‘See? Not very bright, am I?’ She walks as though she’s on springs, her long legs striding, her chin held high. I trudge next to her, feeling too hot, my thighs rubbing together.

Hesitantly I say, ‘I could … I mean, I could help you, if you want. With your GCSEs – your coursework and stuff.’

She looks at me in surprise. ‘For real? That would be amazing!’ She bumps her shoulder against mine. ‘Seriously, that’s really nice of you.’

I bite my lip, trying to contain the smile that’s threatening to split my face in two.

We walk in silence for a while but as we leave the square she tells me why she moved to Fremton. ‘It’s my nan’s old place, but she died last year. My mum had a car accident and she can’t work any more, so we moved down here to save on rent while she gets better.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry about your mum,’ I say.

‘Don’t be,’ she replies breezily. ‘She’ll be fine. She doesn’t care about me anyway, and neither does my dad – not that I’ve seen him for years.’

I’m shocked by her words, how casually she says them – I could never imagine speaking about my own parents like that.

‘You’re easy to talk to, you know,’ she says suddenly.

‘Am I?’

‘Yeah. Haven’t you noticed how most people when you’re talking to them are just waiting till it’s their turn to speak? You actually listen. It’s nice.’ Her face darkens and she adds, ‘Not that I’ve had anyone to talk to since Mum dragged me away from all my friends – and she certainly doesn’t give a shit, that’s for sure.’

I don’t know what to say to this, and we walk in silence until we turn the corner into Heartfields, where I live, and she brightens again. ‘How about you, anyway? You lived here long?’

So I tell her about our old village in Wales, and how we moved down here, and though I don’t mention Lydia or the way my parents barely speak to each other any more, I somehow find enough to say that we’re almost at my house before I realize I haven’t stopped talking once. ‘Sorry,’ I say, putting my hand to my mouth. ‘I’m going on and on, aren’t I?’

She shrugs. ‘So?’

‘Mum says you should only speak if you can improve upon the silence.’

‘Yeah?’ She raises her eyebrows. ‘Your mum sounds like a right laugh.’

‘No,’ I say, surprised. ‘No, she’s really not.’

She smiles at that, but I’m not sure why.

‘Come on,’ she puts her arm through mine, ‘this your street, is it?’

I hadn’t expected Edie to actually want to come home with me, but she follows me up our front path and waits expectantly as I dig around for my keys. ‘Wow,’ she says. ‘Nice house.’ And as I look at her I see Edie through my mother’s eyes: the make-up and short skirt, the cigarette that she’s only now dropping to the ground. Sure enough, as soon as I open the door, Mum appears, stopping in her tracks in the hallway as she looks past me to Edie.