Glorious Deeds of Australasians in the Great War

"What gave you the courage for that heroic dash to the ridge, boys? British grit, Australians' nerve and determination to do or die, a bit of the primeval man's love of a big fight against heavy odds. God's help, too, surely.

"Dear boys, I'm sure you will feel a little rewarded for your deeds of prowess if you know how the whole Commonwealth, nay, the whole Empire, is stirred by them. Every Sunday now we are singing the following lines after 'God save the King' in church and Sunday school. They appeared in the Argus Extraordinary with the first Honour Roll in it:

God save our splendid men!Send them safe home again!Keep them victorious,Patient and chivalrous,They are so dear to us:God save our men."What can I say further? With God the ultimate issue rests. Good-night, boys. God have you living or dying in His keeping. If any one of you would like to send me a pencilled note or card I'll answer it to him by return. – Your countrywoman,

"Jeanie Dobson."That Australian purses were opened with Australian hearts is proved by the remarkable total of gifts in money and kind made by Australia to various funds on behalf of sufferers by the war. In the first ten months the Commonwealth contributed in cash the sum of £2,329,259 to the various funds arising out of the war, apart from immense gifts in kind, the value of which is not estimatable. The State contributions are totalled as follows: – New South Wales, £980,889; Victoria, £850,000; Queensland, £200,825; South Australia, £127,540; Tasmania, £36,750; and Western Australia, £133,255. Total, £2,329,259.

The Australian care for the wounded is the subject of a testimony from Sir Frederick Treves, which may be included here to show the appreciation with which this care has been met by the most eminent surgeon in the Empire: —

"The generosity with which Australia has provided motor ambulances for the whole country, and Red Cross stores for every one, British or French, who has been in want of the same, is beyond all words. I only hope that the people of Australia will come to know of the admirable manner in which their wounded have been cared for, and of the noble and generous work which that great colony has done under the banner of the Red Cross."

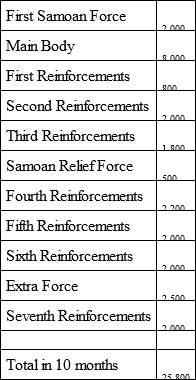

New Zealand is no whit behind Australia; indeed, in proportion to population, the Dominion supplied more men during the first ten months of the war than even the Commonwealth. The troops actually sent on active service by this community of a little more than a million people were: —

Throughout this period the Dominion held a valuable reserve in hand, for the minimum age had been kept at twenty years. This excluded a fine body of young men between the age of eighteen and twenty, all of them well trained under the compulsory system; as grand a body of young soldiers as the world can show. Their number is estimated at 22,000, and over 90 per cent. of them have volunteered for service abroad. At the time of writing the question of lowering the age limit to eighteen was being considered in New Zealand, though the number of recruits of the standard age was still so satisfactory that the step was not necessary. New Zealand is preparing, like Australia, to send out five per cent. of its whole population to fight the battles of the Empire abroad; that is a force of 50,000 men. The whole number of men of military age in the Dominion is less than 200,000.

Those who remain for the defence of the Southern nation are now busy in preparing munitions for the Great War. The factories of the young nations have already been converted into arsenals under the control of Munitions Boards, and hosts of volunteers are working long hours to supply the men of Australasia with every requisite for victory.

Lastly, Australasia has not forgotten that the duty of providing the Empire's food is one of the most important within her province. The year of the outbreak of war saw her producing industries hampered by a disastrous drought, so that the harvest failed and less than twenty per cent of the anticipated wheat supply was garnered. The year 1915 saw quite a different state of affairs; bountiful rains prepared the way for huge crops, and the farmers had sown lavishly, so that full advantage might be taken of this favourable state of affairs.

The wheat crop of 1915-16 nearly doubled the previous record for an Australian harvest. It was garnered by boys and old men and women. Over 200,000 tons of this precious wheat was placed at the disposal of the Allied nations, its freighting and sale being made a national affair. Thus Australia was able to supply 200,000 tons of wheat as one contribution to the fighting forces of the Allies, and was a price as obtained never before approached in the history of Australian agriculture, the Commonwealth was the better able to bear the burden of warfare the Australians had so generously taken on themselves.

Thus Australasia keeps a watchful eye on the gaps wherever they occur, and sets about filling them with a single-minded devotion to the great object which has obliterated all other consideration in the minds of those young nations of the peaceful lands beneath the Southern Cross.

CHAPTER XXV

THE ARMIES OF AUSTRALASIA

Until the year 1870, the Imperial Government maintained a small body of troops in Australia for the defence of the country. They existed for two purposes: the chief one being to protect the country from risings of the convicts. The other purpose was to assist in repelling any foreign invasion, for they formed the garrisons of the rather primitive forts which protected some of the Australian harbours. From time to time local defence bodies were formed, when the troubles of the Mother Country seemed to bring a foreign invasion among the actual possibilities of Australian history. As soon as the trouble, whatever it might be, had blown over, these defence organizations would die a natural death, to be revived when fresh clouds appeared upon the horizon.

The withdrawal of the Imperial troops in 1870 forced each Australian state to initiate measures for defence, and caused the establishment of a small professional army in each of the six separate states, that were later federated into the Commonwealth of Australia. These very small groups of soldiers were designed to form a nucleus for a citizen defence force. This was purely voluntary, the men of Australia drilling and training without any payment; and the Governments finding uniform and weapons, and allowing a fairly large supply of ammunition for practice, at a very cheap rate.

In 1880 a militia system was substituted for the volunteer system, and a yearly payment of something like £12 for each volunteer soldier was arranged. At the same time an admirable cadet system was established, and the schoolboys of Australia entered into the business of drilling, training and shooting with an enthusiasm that did much to keep the ranks of the militia full, as they grew up. The smaller country settlements also established rifle clubs, which had a remarkably large membership. A little drill was combined with a great deal of shooting under service conditions, and to the rifle clubs Australia owes the possession of a very large number of sharpshooters that certainly have no superiors in the world.

The cadets attracted the notice of King George when, as Duke of York, he made his great Empire tour in 1900. They took part in a remarkable review of defence forces held on the famous Flemington racecourse; and Mr. E. F. Knight, one of the London journalists who accompanied the King on that tour, wrote of them in the following terms: —

"The first to pass the saluting base were the cadets, who to the stirring strains of the British Grenadiers marched by with a fine swing and preserved an excellent alignment. They presented the appearance of very tough young soldiers, and they exhibited no fatigue after a very trying day, in the course of which they had been standing for hours with soaked clothes in the heavy rain. They looked business-like in their khaki uniforms and felt hats.

"During the march past I was in a pavilion reserved chiefly for British and foreign naval officers. The German and American officers were much struck with the physique and soldierly qualities of the Australian troops, but they spoke with unreserved admiration when they saw these cadets."

The cadet system was elaborated, between the years 1909 and 1911, into a system of compulsory military training based on a scheme drawn up by Lord Kitchener himself, followed by a report on Australian defences made by Sir Ian Hamilton, the General who is now in supreme charge of the Australasian forces at the Dardanelles. When the new scheme came into force, the numbers of the land forces of the Commonwealth were nearly 110,000 men and boys; the figures comprising 2,000 permanent troops, nearly 22,000 militia, over 55,000 members of rifle clubs, and 28,000 cadets.

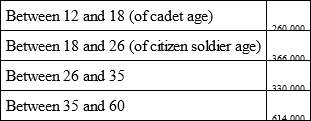

At the time the new compulsory system came into force, the number of males in Australia was —

For compulsory training it was enacted that the citizens of cadet and military age should be divided into four classes as under: —

Junior Cadets, from 12 to 14.

Senior Cadets, from 14 to 18.

Citizen soldiers, from 18 to 25.

" " 25 to 26.

The prescribed training was: (a) For junior cadets, 120 hours yearly. (b) For senior cadets, 4 whole-day drills, 12 half-day drills, and 24 night drills yearly. (c) For citizen soldiers, 16 whole-day drills, or their equivalent, of which not less than eight should be in camps of continuous training.

The scheme came into operation at the beginning of 1911, when the new cadets, to the number of over 120,000, were enrolled. At the same time 200 non-commissioned officers, as a training force for the new army, went into camp for a six months course of instruction. From July 1 the new system of cadet training began, 20,000 of the boys, of the age of eighteen, going into training as the first year's crop of recruits. Every year afterwards this number, approximately, of trained senior cadets was added to the citizen army in training, while the number of cadets remained about 120,000; some 20,000 junior cadets at the age of twelve reinforcing the cadets as each draft of eighteen-year-old cadets became citizen soldiers.

It will be seen that the outbreak of the war in 1914 found the Australian scheme still incomplete, since the number of citizen soldiers in training was approximately only 80,000, even including the 20,000 cadets of that year, who had just been drafted into the citizen army.

Australia had also arranged for the training of its own young officers, who in time should develop into Area Officers under the compulsory services scheme, which provides for the division of the Commonwealth into over 200 military Areas, with an officer in charge of each. The establishment of a military college at Duntroon, near the new Australian Federal capital city of Canberra, had made excellent progress when war came.

The Duntroon establishment was an efficient rather than a showy establishment; its modest wooden bungalows, in which the officers were quartered, contrasting strangely with the elaborate arrangements at similar establishments such as Sandhurst or West Point. But the teaching was remarkably thorough for such a young institution. The democratic tendencies of Australia are illustrated by the fact that tuition at Duntroon is absolutely free, the parents of the young officer being not even asked to supply him with pocket money, since an allowance of 5s. per week is made by the Government to each cadet in training. The course of instruction is one of four years' training, and necessitates the daily application of six hours to instruction, and two hours to military exercises. A vacation of two months is observed at Christmas time, the height of the Australian summer, and there are frequent camps for practical instruction in all branches of field work.

Cadets are required to make their own beds, clean their own boots, and keep their kit in order. Special emphasis is laid upon the value of character, and any cadet, however able in acquiring knowledge or brilliant in physical exercises, must, if he lacks the power of self-discipline, be removed as unfit to become an officer who has to control others. The College was opened in June, 1911, with forty-one cadets, and has since been employed by the New Zealand Government for the training of its young officers, a step in co-operation which is likely to show the way to still closer relations between the Dominion and the Commonwealth in many matters relating to defence.

The Commandant of the College was the late General Bridges, whose death in action at Gaba Tepe is so universally mourned by Australians. Writing of him and the College in the Sydney Morning Herald, V. J. M. says: —

"Duntroon is his masterpiece. To have left it as he did, after a bare four years, represents the greatest educational feat yet accomplished in Australia. Before attempting it he studied the greatest colleges in Europe and America – Sandhurst, Woolwich, West Point, Kingston, Saint-Cyr, L'Ecole Polytechnique, L'Ecole Militaire, die Grosslichterfelder Kadettenanstalt – all were visited and carefully investigated by him. His endeavour was to incorporate, so far as local conditions would allow, the best of each in Duntroon. How far he has succeeded is well known. In the opinion of Viscount Bryce, Sir Ian Hamilton, Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson, and others, it stands out one of the most efficient military schools – some say the most efficient – in the world. Four years ago there were a station homestead and a rolling sweep of lonely country. What a strong driving force must have been behind it all. The crisis found Duntroon ready. Already seventy-one officers from its class-rooms and training fields are at the front, of whom some twenty have fallen. So excellent has been the work of these young soldiers in the desert camp that, in a recent letter, General Bridges mentioned that General Birdwood has specially written of them to the King. Australia will have reason in the troublous years ahead to be thankful that her great military school was conceived by a man of broad grasp and wide knowledge. The soldiers of the future will be moulded and the armies of the future organized by its graduates. He meant it to be, and it is, a great military university."

The precedent that Australasian soldiers should take part in the wars of the Mother Country was set in 1883, when the State of New South Wales sent a contingent of 800 infantry and artillery to the Soudan. The initiative in this matter was due to Mr. W. B. Dalley, then Premier of New South Wales. The force, after being reviewed by Lord Loftus, the State Governor, sailed from Sydney on March 3, 1883, on the transports Iberia and Australasian. The services rendered by them were comparatively slight; indeed, they were treated by the Imperial authorities as rather a gratuitous nuisance, intruding where their presence was not required. But the precedent had been set, and was followed by all the Dominions Overseas, on the outbreak of the African war.

Once again the War Office was inclined to regard the Greater Britons as useless interlopers, and the offer to provide cavalry was met with the historical cable that in Africa "foot soldiers only" were required. It is further a matter of history that the authorities very sensibly revised this estimate as the war progressed, and were glad of the services of every man who could ride and shoot. Contingent after contingent was despatched from Australasia, New Zealand especially providing a wealth of fine soldiers. In proportion to population, the Dominion supplied more men to fight the Empire's battle in South Africa than any part of the British realm.

CHAPTER XXVI

CLEARING THE PACIFIC

When the war broke out, the ports of Australasia lay within striking distance of German harbours, where lay a powerful squadron of armoured and light cruisers. A very real danger to Australasian shipping and seaports had to be encountered; and the first warlike steps taken by Australia and New Zealand were expeditions against Germany's Pacific Colonies.

At that time they were very considerable possessions, about 100,000 square miles in extent. Chief among them was Kaiser Wilhelm's Land, or, to give it its British appellation, German New Guinea, contiguous to the Australian possession of Papua, and 70,000 square miles in area. Next came the Bismarck Archipelago, better known as New Britain, a group of islands with an area of 20,000 square miles. Other colonies were German Samoa, and the Caroline, Marshall, Ladrone, Pelew, and Solomon Islands. In these colonies were established wireless stations of great strategical importance to Germany.

The squadron maintained to protect these possessions was a very modern and powerful one, as Great Britain was to learn to her cost. It consisted of the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and the light fast cruisers Leipzig, Nürnberg, and Emden. The units of the British navy on the spot were the three old third-class cruisers Psyche, Pyramus, and Philomel; and upon these New Zealand, the Dominion most threatened, would have been forced to rely if Australia had not been provided with a navy of her own.

That navy had made ready for sea at the first sign of a great European war, and met at an appointed rendezvous off the coast of Queensland on August 11. One section of it, consisting of the battle-cruiser Australia, the light cruisers Sydney and Melbourne, and the destroyers Parramatta, Yarra, and Warrego, set off to the Bismarcks in the hope of encountering the German squadron. The destroyers, under convoy of the Sydney, made straight for Rabaul, the chief German settlement there, although there were no charts of the harbour, while the big ship and the other light cruiser kept watch at a distance.

In the darkness of a pitch-black night the destroyers steamed into the harbour, and captured all the ships in the bay. Right up to the pier they steamed, and then out again, having effected their purpose for the time being. They set out from that point to a rendezvous at Port Moresby, in Australian New Guinea, while the Sydney returned to Australian waters. The Australia and the Melbourne made for New Caledonia, where their presence was needed in aid of the Sister Dominion of New Zealand.

With the greatest secrecy the New Zealand Government had equipped a force of 1,300 volunteers from the province of Wellington, for an expedition against German Samoa. They knew the big German warships were somewhere in the vicinity, but that risk did not deter them. The men were sent on transports, and convoyed by one of the antiquated British cruisers; their first port of call was New Caledonia, distant five days. Fortune favours the brave, and this was a brave little adventure, if ever there were one such. But they won out all right, reaching New Caledonia safely, to receive a joyous welcome from the Australia, the Melbourne, and the French cruiser Montcalm, which were awaiting them at Noumea.

Their course to Samoa was now a safe one, comparatively speaking, and they had the satisfaction of lowering the German flag at Apia, and hoisting the Union Jack in its place, before the war was a month old. The warships left the Expedition in possession, and steamed away. A fortnight later the two big German ships were sighted off the harbour, and the little garrison had a thrilling experience. They prepared to defend the place against the heavy guns of the Germans, but it was not necessary. After some delay the Germans, apparently fearing some trap, steamed off, and were not again seen in the vicinity.

Samoa fell on August 29, and on September 9 the Australia and the Melbourne were keeping another rendezvous at Port Moresby. Their appointment was with the transport Berrima, which, escorted by the cruiser Sydney, conveyed to that port an Expedition launched against the German Colonies in the North Pacific. It consisted of six companies of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve, under Colonel Holmes, D.S.O., and a battalion of infantry with machine-guns. With the Berrima were the two Australian submarines AE1 and AE2, both of which came to an untimely end before the war was nine months old. At the rendezvous were the destroyers, a transport with 500 Queensland soldiers, and store ships and other requisites for such an expedition.

The objects of the expedition were two; they meant to occupy Rabaul, the chief settlement in the Bismarck Archipelago, and to destroy the German wireless station they knew to be established somewhere in Neu Pommern, the principal island in the group. The Australia, with the transports, made straight for Rabaul, which capitulated. The destroyers, under convoy of the Sydney, were sent forward to search for the wireless station. The first landing party marched straight inland, and soon encountered trouble. A heavy fire was directed upon them from sharpshooters, who were so well hidden that it was suspected they were in the trees; and the Australians were forced to take to the bush. They signalled for help, and also worked through the dense scrub until they came upon an entrenched position.

The signal for help brought every available man from the destroyers ashore; a picturesque touch was added to the reinforcement by the uninvited presence of one of the ship's butchers, who attached himself to the party in a blue apron, and armed with his cleaver of office. This relief party was followed by two others, one landing at Herbertshöhe to execute a flank movement. The first party had some stiff bush fighting, in which Lieutenant Bowen was wounded, and three Germans were captured. When the first two forces joined hands, Lieutenant-Commander Elwell was shot dead; and they were glad to see the main expeditionary force, with machine-guns, arrive on the scene of action.

The machine-guns settled the question, and the German commander, Lieutenant Kempf, at once hoisted the white flag. With some Australians he proceeded to a second line of trenches, and ordered the occupants to surrender. A number of them were taken prisoners; and then resistance broke out, and they all tried to escape. They were fired upon, and eighteen were shot in the act of running away. In the end the remainder were content to surrender.

The surrender of the wireless station was negotiated by Lieutenant Kempf himself, after giving his parole. He cycled alone to the place, and announced that he had arranged that there should be no resistance. Three Australian officers followed him and, placing reliance upon his word, boldly entered the station late at night. They found it strongly entrenched, but the natives who formed the majority of the defending force had quite understood Admiral Patey's threat that he would shell the place unless the flag were hauled down, and had no relish for such an ordeal. The next afternoon the British flag was hoisted over the station.

The next objective was Toma, a town inland whither the German administrator of the Colony had fled when the warships appeared before Rabaul. An expedition against this place, with the complement of a 12-pounder gun, was accordingly arranged. The Australia paved the way for this expedition by shelling the approaches to the town, with the result that a deputation was sent out by the Administrator to meet the force half-way. The column continued its march without paying any attention to this deputation, and entered Toma the same day in a dense cloud of tropical rain.

The Administrator sent another messenger to the officer in charge, promising to repair to Herbertshöhe the next day to negotiate a surrender. As the French cruiser Montcalm had now arrived the most sanguine German could not expect any continued resistance, and the surrender was signed.

Thus on September 13 all resistance had been crushed in the Bismarck Islands, and the Colony had been reduced by the Australians at a cost of two officers killed – Captain Pockley and Lieutenant-Commander Elwell – and three men. One officer, Lieutenant Bowen, and three men were wounded.