По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

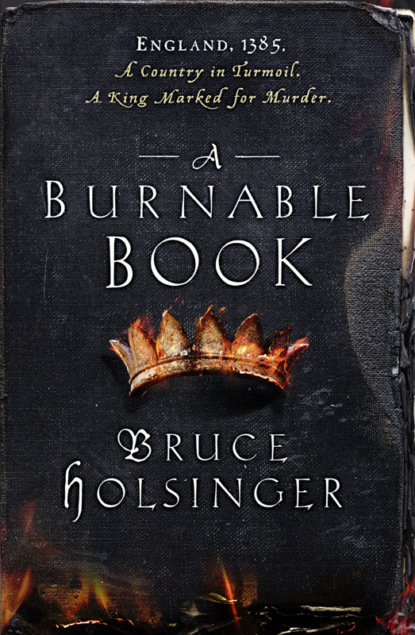

A Burnable Book

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Full oft there shall you comfort and entwine

His long limbs in bookish fetters benign.

Thou shalt preserve those aquamarine gems,

Or Gower’s friend shall cast you in the Thames.

As always Chaucer’s verse captured its subject with the precision of a mirror. My thinning hair, shot through with spreading grey. My long frame, which had two lean inches on Chaucer’s, and he was not a short man by any measure. Finally the eyes. ‘Gower green,’ a limner I once knew named their shade, claiming no success in duplicating it. Sarah had always likened them to her native Malvern Hills at noon, though she had died without fathoming the truth about these eyes, and their diminishing powers. Only Chaucer possessed that knowledge, expressed in a touching bit of protectiveness in the couplet.

I looked up to see him staring vacantly at the far wall. I closed the book.

‘Why did you want to meet here of all places?’

‘I’m less known in Holbourne,’ he whispered, in French, teasing, ‘where there’s smaller chance of recognition than within the walls.’

‘Ah, I see,’ I replied, also in French. ‘I am the object of a secret mission, then. Like your visits to Hawkwood and the Florentine commune.’

His smile dimmed. ‘Hawkwood. Yes. You know, I spent some time with Simon while I was in Florence.’

‘God’s blood, Geoffrey!’

He looked uncomfortable. ‘You didn’t write to him after Sarah died.’

‘No.’

‘He’s your son, John. Your sole heir.’

The child who survived, when three others did not. I drained my jar, signalled the girl for another.

‘Have you heard from him?’ he asked, reading my thoughts.

A fresh dipper, and I drank deeply. ‘Tell me about your sons instead,’ I said, in a feeble change of subject. ‘How is Thomas faring at the almonry?’

‘Well enough, I suppose,’ he said.

‘And little Lewis?’

‘With his mother, the little devil.’ He gave a half shrug. ‘Some call him the devil, our Hawkwood. But I suppose our king knows what he’s doing when it comes to alliances.’

‘What few of them he has left,’ I said.

He looked at me, smiling. ‘No King Edward, is he?’

I held up my jar. ‘Full long shall he lead us, full rich shall he rule.’

His smile faded. ‘Wherever did you pick that up, John?’

‘A preacher, versing it up out on Holbourne just now.’

‘Our sermonizers are quite poetical these days, aren’t they?’ he scoffed. There was a certain strain in his voice, though I thought nothing of it at the time.

‘Fools, if you ask me, to versify on that sort of matter,’ I said.

‘Better to stick to Gawain and Lancelot, I suppose.’

‘Or fairies.’

‘Or friars.’

We laughed quietly. There was a long silence, then Chaucer sighed, tapped his fingers. ‘John, I need a small favour.’

Of course you do. ‘Go on.’

‘I’m looking for a book.’

‘A book.’

‘I’ve heard it was in the hands of one of Lancaster’s hermits.’

I watched his eyes. ‘Why can’t you get it for yourself?’

‘Because I don’t know who has it, or where it is at the moment.’

‘And who does know?’

He raised his chin, his jaw tight. I knew that look. ‘Katherine Swynford, perhaps. If a flea dies in Lancaster’s household she’ll have heard about it. Ask her.’

‘She’s your sister-in-law, Geoffrey.’ I felt a twinge of misgiving. However innocent on its face, no request from Chaucer was ever straightforward. ‘Why not ask her yourself?’

‘She and Philippa are inseparable. Katherine won’t see me.’

‘So you’re asking me to approach her?’

He took a small sip.

‘Why me?’ I said.

‘How to put it?’ He pretended to search for words, his hands flitting about on the table. ‘This job needs a subterranean man, John. A man who knows this city like the lines in his knuckles, its secrets and surprises. All those shadowed corners and blind alleyways where you do your nasty work.’

I gazed fondly at him, thinking of Simon, and so much else. It was one of the peculiarities of our intimacy that Chaucer seemed to appreciate talents no one else would value in a friend. Here comes John Gower, it was murmured at Westminster and the Guildhall; hide your ledgers. Hide your thoughts. For knowledge is currency. It can be traded and it can be banked, and more secretly than money. The French have a word for informers: chanteurs, ‘singers’, and information is a song of sorts. A melody poured in the ears of its eager recipients, every note a hidden vice, a high crime, a deadly sin. Or some kind of illicit antiphon, its verses whispered among opposed choirs of the living and the dead.

We live in a hypocritical age. An age that sees bishops preaching abstinence while running whores. Pardoners peddling indulgences while seducing wives. Earls pledging fealty while plotting treason. Hypocrites, all of them, and my trade is the bane of hypocrisy, its worth far outweighing its perversion. I practise the purest form of truthtelling.

Quite profitably, too. The second son of a moderately wealthy knight has some choices: the law, the royal bureaucracy, Oxford or Cambridge, the life of a monk or a priest. Yet I would rather have trapped grayling in the Severn for a living than taken holy orders, and it was clear that my poetry would never see the lavishments from patrons that Chaucer’s increasingly enjoyed. Yet I shall never forget the thrill I felt when that first coin of another man’s vice fell into my lap, and I realized what I had – and how to use it. Since then I have become a trader in information, a seller of suspicion, a purveyor of foibles and the hidden things of private life. I work alone and always have, without the trappings of craft or creed.

John Gower. A guild of one.

‘You can’t be direct with her about it,’ Chaucer was saying. ‘This is a woman who takes the biggest cock in the realm between her legs. She’s given Lancaster three bastards at last count – or is it four?’ He waited, gauging my reaction.