Charles Bradlaugh: a Record of His Life and Work, Volume 1 (of 2)

61

Meanwhile the Park was occupied by the military and the police in readiness to clear away the "infidels" should they appear.

62

National Reformer, the Western Morning News, and Western Daily Mercury.

63

The Western Times (Exeter, August 3rd), a hostile paper, said: "The plaintiff certainly established his case, and the verdict was on the face of it ridiculous." "The religious feelings of the jury neutralized the spirit of the law by the ridiculous 'damages' which they awarded for his wrongs."

The Morning Star (August 2nd) had a most indignant article, condemning such a verdict "as a flagrant denial and mockery of justice." The Bradford Review was courageously outspoken, and urged that a new trial should be moved for.

In a leaderette the Weekly Dispatch (August 4th) thought that this Devonshire dealing was altogether a scene for Spain rather than for England, and condemned Mr Collier's conduct of the case. In the following issue Publicola had a long article on the proceedings, in which he deplored "that such an institution as that of trial by jury, to which we are indebted for magnificent assertions of political right and freedom, which, generally speaking, is a safeguard against social injury, should, by the conduct described, become a portion of the machinery of persecution."

Punch (August 10th) joined in its voice, and published a flippant article on "A Short Way with Secularists," in which it tells the story of the seizure of "that fellow Bradlaugh, who calls himself Iconoclast," and hailed with mock delight the advent of the "orthodox reaction." Said Punch, "The magistrates becoming judges of controversy, and the policemen forcing their decrees, the office of justice of the peace will become a holy office indeed, and the constabulary will rise into familiars of a British Inquisition."

Not the least remarkable article appeared in the Catholic Tablet for August 3rd. It speaks of the arrest and imprisonment of Mr Bradlaugh as "frightful persecution," and says: "His legal rights have been violated by the police, and a jury of British Protestants have refused him redress, because his interpretation of the Scriptures is different from theirs. Either that is religious persecution or there is no such thing."

In 1861 the English Roman Catholics regarded Mr Bradlaugh as a weak and (to them) harmless unit, and they affected to espouse his cause as a weapon against their deadly enemies, the Protestants. What a change in less than twenty years to the time when "Henry Edward, Cardinal-Archbishop," and Prince of the Church of Rome, thought it necessary, with his own powerful hand, to write protest after protest in the Nineteenth Century, against Mr Bradlangh being allowed to take his seat in the Commons House at Westminster! What a change from 1861 to 1882, when this same great prelate thought it necessary to pay a formal visit in solemn state to the town of Northampton itself to use his mighty influence to turn the electors against "this poor Secular Iconoclast," as the Tablet once called him.

64

This refers to the decision of the Devonport Town Council.

65

Shorthand report.

66

National Reformer, March 9, 1861.

67

C. Bradlaugh in National Reformer, Jan. 12, 1861.

68

Mr Barker's lecture (p. 121) was a month or two later.

69

A correspondent to the Oldham Standard enjoined upon his fellow Christians that it was their duty "to root out of our establishments every one advocating his principles, for the safety of those committed to our care, and the honour of our God. Let us do this and 'Iconoclast,' will fall to the ground and never again rise. His object is to live upon the pence of his deluded hearers, and, after a time, when he has become old and infirm, to turn round, and by a recantation of his present teaching worm himself into comfortable bread as a reclaimed infidel."

The North Cheshire Herald, in alluding to some lectures delivered by Mr Bradlaugh at Hyde, in the summer of 1861, said: —

"In justice to 'Iconoclast,' we must say he possesses great oratorical powers, and he has, so far as the ignorant are concerned, a very pleasing way of practising on their gullibility. He is cunning to a degree, but his object may be seen through without the aid of spectacles. It is evident that he means money; for when it is known that he received £5 for using such blasphemous language as would not be uttered by the very lowest of the 'fallen' class, the fact is indisputable… We sincerely hope that God will change his heart, and that when he is about quitting this sublunary world, he will not be heard exclaiming, as other infidels have done, 'What shall I do to be saved?'"

70

In National Reformer of that date.

71

In National Reformer, June 1861.

72

C. Bradlaugh in National Reformer.

73

Towards the end of November 1862 death claimed him who had been to my father "friend, tutor, brother." When the exile was buried, Mr Bradlaugh wrote that "the proscribed of all the Nationalities of Europe mustered round his coffin to do him honour. Italy, Germany, Russia, Poland, Hungary, and France were numerously represented; and long ranks of the best and bravest of banished men trod in sadness in the rear of the funeral hearse." By the open grave at Kilburn, "amongst the hundreds of intellectual looking men here might be seen most noticeable the bearded figure of that most omniscient of political writers, Alexander Herzen; here the stalwart frame of the escaped Bakunin; here the saddened features of an old Englishman [Thomas Allsop] who had borne part with him in his political struggles, and who had loved the dead man with the fullest friendliness of his most honest nature." At the grave side spoke M. Talandier; my father spoke, also Mr G. J. Holyoake, M. Gustave Jourdain, and then M. Felix Pyat, whose fiery sentences were followed by the dull and mournful echo of the earth falling upon the coffin lid.

74

This was in December 1874.

75

Contrast the delicate words of personal description written by a Christian in the Clerkenwell News: "The manner and appearance of the minister and the Atheist were as much at variance as the Gospel of the one is with the 'reasoning' of the other. The one with a kind, affectionate air – a calm self-reliance, resulting from faith in a beneficent God and loving Redeemer – was a fit defender of love and mercy. On the other hand, the Atheist's looks stamped him as a low demagogue. He was throughout restless; now displaying his ring, after admiring it himself; now turning with an idiotic grin towards his followers, who certainly resembled Falstaff's recruits in appearance; and throughout conducting himself as a boastful, ill-bred man. His personal appearance did not aid him, for it partook of that animal which is said much to resemble some men. His voice, like the whine of a dog, was rendered more unpleasant by a spluttering lisp, occasioned by his inability to bring his lower jaw forward enough to meet his protruding upper lip."

76

This was in 1862, before the Evidence Amendment Act, 1869, and Mr Bradlaugh's Oaths Act, 1888.

77

See "Poems, Essays, and Fragments." (A. and H. B. Bonner)

78

Despite the sharpness – to use no harsher term – of Mr Cooper's words and manner towards him, my father bore no malice, and showed himself quite ready to forgive and forget. A few months later, hearing that Mr Cooper was in very straitened circumstances, he expressed his desire to be allowed to join in the scheme for assisting his old opponent, for he believed him "to have been a well-intentioned, warm-hearted man, and one who, as a politician, has done good work."

79

National Reformer, June 24th, 1866.

80

National Reformer, June 24th, 1866.

81

"Look at me," said Bagheera, and Mowgli looked at him steadily between the eyes. The big panther turned his head away in half a minute.

"That is why," he said, shifting his paw on the leaves, "not even I can look thee between the eyes, and I was born among men, and I love thee, little brother. The others they hate thee, because their eyes cannot meet thine; because thou art wise; because thou hast pulled out thorns from their feet; because thou art a man!"

Mowgli's Brothers, by Rudyard Kipling.

82

Morning Advertiser.

83

Mr Robert Forder, who was present at the Garibaldi meeting, sends me the following vivid account of what took place on that day: —

"That afternoon," he relates, "was the first time I had the honour and pleasure of speaking to your father. A few of us at Deptford, where I then resided, had had printed a quantity of handbills announcing the debate with the Rev. W. Barker, then appearing in the National Reformer. I gave your father one, for which he thanked me. I should like, with your permission, to add a few words as to what took place on that exciting afternoon. The Irish Catholics had been well whipped up for the occasion, and were there in force; most of them dock and bricklayers' labourers, and in the mass totally uneducated. There were three mounds of earth and stones intended to repair or make roads, each about four feet high, and, so far as I can recollect after thirty years have gone by, about thirty yards long by eight deep. These were about fifty yards apart, and on the middle one were gathered the men and two women – one of the latter in a red 'jumper,' that was afterwards known in fashion as a 'Garibaldi.' The Irish were massed on and around the two other mounds, and during the early part of the proceedings contented themselves with singing a refrain for 'God and Rome.' It was about ten minutes after your father had begun to speak that a signal was given, on which a sudden rush was made upon the meeting. There had not been up to this moment any indication whatever that the Irish were armed, but every man and woman (and there were many women and girls with them) was possessed of a bludgeon of some sort. Their onslaught was furious and brutal, and for a time successful. They carried the mound in a few minutes, but the blood upon many of our friends aroused such a feeling of indignation, that in a time less than it takes me to write it the mound was stormed from the Piccadilly side, and again captured by us. There were in the crowd about a dozen Grenadier Guardsmen, who were ardent admirers of Garibaldi, and there were quite fifty others, possibly passive spectators. The former formed two deep, and with their walking-sticks rushed down the mound into the mass of the yelling Irish. The effect was electrical. Their comrades in the crowd raised a sudden shout, and in ten minutes the Irish were in full retreat, throwing away their sticks to escape the indignation of the people they had so wantonly and brutally attacked. Many were captured by the police, and I clearly remember the constables gathering up their bludgeons, and making bundles of them with their belts. It must be confessed that no quarter was given, and scores of them got severely mauled. Cardinal Wiseman referred to the brutality of the infidel mob in a pastoral a few days after, in which he used the term 'lambs' to describe these religious ruffians. Punch, the next week, 'caught on' to this word, and in its weekly cartoon depicted this mob of Irish assailing a public meeting over the heading of 'Cardinal Wiseman's Lambs.'"

84

He gave two lectures in the Mechanics' Institute (lent to the Freethinker for this occasion), and the proceeds, £8 11s. 4d., were handed over to the fund. "No lecturer gave more to the needy than Iconoclast," said Mr Austin Holyoake.

85

One of the latest letters he ever wrote, bearing date Jan. 12, 1891, shows him always the same. He says: "I am extremely sorry to read your letter, but I have, unfortunately, no means whatever except what I earn from day to day with my tongue and pen. If the Committee think it wise, I will lecture for the benefit of such a fund."

86

The number of persons present was variously estimated at from 30,000 to "upwards of 60,000."

87

Mr Bradlaugh commented somewhat epigrammatically: "The Right Hon. Benjamin Disraeli is perhaps the man best fitted to be in opposition, and the least fitted to govern amongst our prominent men. His waistcoats have been brilliant, but his Parliamentary measures cannot always successfully compare with the result of his tailor's skill."

88

The Bristol Daily Post.

89

Bedford Mercury of November 24th.

90

The Morning Star (London) of November 22nd also notes the enthusiasm provoked by Mr Bradlaugh's "animated speech."

91

Essay in Cornhill Magazine, 1868, reprinted in book form as "Culture and Anarchy."

92

In a general "damnatory" description of the demonstration given from "a club window," which appeared in the Times of February 12th, there is a caricature of Mr Bradlaugh, spiteful in intent, but amusing and really interesting if one looks between the would-be scornful words. We are told that "a dapper youth, mounted on a brown horse, exerted himself to make up for the shortcomings of the public force, and was a host in himself. He was evidently a man in authority, and acted in close connection with the Reform magnates, whose carriages stopped the way before our doors. He raised his whip as freely as if it had been a constable's truncheon or gendarme's broad-sword, and apostrophised, or – why should I not say the word – bullied the crowd in a tone and with manners which would have done an alguazil's heart good. The sovereign people put up with the man's arrogance with incredible meekness and patience, and allowed itself to be marshalled hither and thither as if the Queen's highway were the Leaguers' special property and the public were mere intruders."

The "Club" man was evidently irritated that these same people who at Hyde Park had refused to obey a police proclamation backed by a free use of the truncheon and display of the bayonet, yet implicitly obeyed the "youth mounted on a brown horse" whose only authority was derived from the love the people bore him. The sneer as to "tone" and "manners" is not worth noticing; you cannot issue commands to tens of thousands in Trafalgar Square in the same gentle tone in which you can ask for the salt to be passed across the dinner-table.

93

March 9th, 1867.

94

Times, March 12th, 1867.

95

The Standard, May 7th.

96

The lectures were announced for the following day.

97

National Reformer.

98

National Reformer, November 4 (1866).

99

On November 25 (1866).

100

C. Bradlaugh in National Reformer, March 1867.

101

No verbatim report of this discussion was ever published.

102

West Sussex Gazette, June 24th. And these are the people who affect to believe in Mr Bradlaugh's violence and coarseness! "Even so ye outwardly appear righteous unto men, but within ye are full of hypocrisy and iniquity."

103

C. Bradlaugh, in National Reformer, July 1869.

104

Of these Darwen lectures all the Preston papers gave long reports. The Conservative Preston Herald thought that "the burning words of eulogium [on Mr Gladstone] that fell from the lips of the clever advocate" laid Mr Bradlaugh "open to the suspicion of having accepted a retainer and a brief from the astute statesman"! About 1200 persons attended each lecture, and the "quiet village of Darwen was rendered as throng as a fair" by the influx of people from so many of the surrounding villages.

105

Autobiography.

106

Headingley, p. 105.

107

Weekly Dispatch, November 16, 1879.

108

Headingley, p. 104.

109

Pamphlet on the Irish Question.

110

National Reformer, October 20.

111

When he republished this as a pamphlet it was read by Mr Gladstone, who wrote to him the following autograph letter: —

"11 Carlton Terrace,July 17, 1868."Dear Sir, – I have read your pamphlet with much interest, and with many important parts of it I cordially agree. – I remain, Dear Sir, yours very faithfully and obediently,

W. E. Gladstone."Mr C. Bradlaugh."

This letter is still in my possession.

112

National Reformer, Feb. 16, 1868.

113

Headingley, p. 107.

114

July 4th.

115

The sitting members were Charles Gilpin and Lord Henley.

116

Souvenir.

117

Daily Telegraph, August 3, 1868.

118

In October Mr Keevil, chairman of the Irish Reform League, wrote again to Northampton. "Our members," he said, "consist of every denomination of Christians, and although we regret that Mr Bradlaugh does not believe in matters of religion as we do, and probably Mr Bradlaugh also regrets that we are not of the same religious opinions as himself, yet we do not think such controversial matters can hinder his usefulness for the people's work in the House of Commons. We in Ireland have had special opportunities of knowing the value of Mr Bradlaugh's works… The field of Mr Bradlaugh's early labours was Ireland; the Lecture Hall in French Street, Dublin, was the arena of his triumphs, and the people soon recognised in him a champion. Private Bradlaugh was well known in County Cork many years ago as a man who would maintain the oppressed tenants against the injustice of landlordism."

119

The latter part of this myth, at least, seems to have gained credence, for in July of this year (1894) Mr Courtney is reported to have said at Chelsea that "Mr Bradlaugh had to try constituency after constituency because he could not get a majority in any particular place."

120

See article on "Electioneering Rowdies," October 1868, in which, with innate delicacy, it speaks of Mr Bradlaugh as "impudent."

121

This song was written by a young shoemaker named James Wilson, and was set to music by another poor but gifted man, John Lowry. Poor Wilson died early, but his song became a sort of war-cry in Northampton, and will live long in the hearts of his fellow-townsmen.

122

Page 28.

123

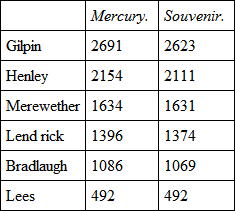

These were the figures given in National Reformer, November 22, 1868. The Northampton Mercury of that week gives them rather differently, and the Souvenir brought out in June 1894 again differently. They give the poll as follows: —

124

Praying that there should be no breach of the peace.

125

Daily News.

126

The Evidence Amendment Act 1869 (32 and 33 Vict. c. 68) enacted "that if any person called to give evidence in any court, whether in a civil or criminal proceeding, shall object to take an oath, or shall be objected to as incompetent to take an oath, such person shall, if the presiding judge is satisfied that the taking of the oath would have no binding effect upon his conscience, make the promise and declaration the form of which is contained in the same section." Mr Prentice, as arbitrator, did not consider himself a "presiding judge" within the meaning of the Act, and was not therefore qualified to satisfy himself as to the state of a witness's conscience.

127

This reply was refused insertion.

128

National Reformer, April 17, 1870.

129

May 22, 1870.

130

This was an action to try the right of the Sheriff of Surrey to distrain upon the Colour Machinery at Hatcham. Baron dos Santos, of the Romish Legation, had wished to trade in Naples colour in England, under the name of the Company of which Mr Bradlaugh was Secretary. Mr Bradlaugh had bought and paid for the machinery to grind the colours before they could be sold, and he claimed to carry on the business until Baron dos Santos should purchase the things off him. Obliged to raise money in 1868, when he was contesting Northampton, Mr Bradlaugh borrowed £600 from Mr Javal upon the machinery, and he in turn raised some money from the Advana Company. Before this last had been repaid the defendants seized the machinery under an execution judgment as creditors of the Naples Colour Company. Mr Bradlaugh was the principal witness, and the newspaper report notes that he requested to be allowed to affirm instead of being sworn, but said that he should take the oath, if his lordship insisted upon it. He was allowed to affirm, and at the conclusion of the case the jury decided that the machinery belonged to Mr Bradlaugh, and therefore gave a verdict for the plaintiffs.

131

May 1870.

132

These cases were so rare that the only one I can actually recall is that of the Tyneside Sunday Lecture Society.

133

See p. 294.

134

At the end of 1872 Mr John Baker Hopkins made a violent attack upon Mr Bradlaugh for his "Impeachment of the House of Brunswick" in the pages of the Gentleman's Magazine. A reply to this from my father's pen appeared in the January (1873) Number, but there was such an outcry raised in the press at the insertion in the "Gentleman's" Magazine of an article by "Mr Bradlaugh of Whitechapel and Hyde Park respectively" that Mr John Hatton, the editor, felt so far obliged to defend himself as to say a word in favour of free discussion. He further atoned for his sins by allowing Mr J. B. Hopkins to return to his attack in the following month.

135

December 1871.

136

"Christianity in Relation to Freethought Scepticism and Faith: three discourses by the Bishop of Peterborough, with special replies by Charles Bradlaugh."

A similar case in a small way happened at Deptford in April 1873. A Rev. Dr Miller had delivered some addresses in the Deptford Lecture Hall against "unbelievers," and it was proposed that Mr Bradlaugh should reply to these addresses in the same place. He had frequently spoken in the Deptford Lecture Hall before, but when the Deptford Freethinkers sought to engage it for a lecture in answer to Dr Miller, the Committee refused to let the hall for that purpose. This intolerance the Kentish Mercury applauded by referring to it in bold type as "noble conduct."

137

September 26, 1871.

138

See Chapter ix., vol. ii.

139

Earl Fortescue at the King's Nympton Farmers' Club, November 1871.

140

Address to the Cardiff Constitutional Association.

141

The Observer's own report stated: "At first there seemed to be an inclination to rush to the doors, which might have led to great sacrifice of life."

142