The Naval Pioneers of Australia

To understand fully what Phillip's good management had effected, without going into detail, it may be said at once that no succeeding voyage, in spite of the teachings of experience, was made with such immunity from sickness or mutiny. The second voyage, generally spoken of as that of the second fleet, for example, was so conducted that Judge-Advocate Collins says of it:—

"The appearance of those prisoners who did not require medical assistance was lean and emaciated. Several of these miserable people died in the boats as they were rowing on shore or on the wharf as they were being lifted out of the boats, both the living and the dead exhibiting more horrid spectacles than had ever been witnessed in this country. All this was to be attributed to confinement, and that of the worst species—confinement in a small space and in irons, not put on singly, but many of them chained together. On board the Scarborough a plan had been formed to take the ship.... This necessarily, on that ship, occasioned much future circumspection; but Captain Marshall's humanity considerably lessened the severity which the insurgents might naturally have expected. On board the other ships the masters, who had the entire direction of the prisoners, never suffered them to be at large on deck, and but a few at a time were permitted there. This consequently gave birth to many diseases. It was said that on board the Neptune several had died in irons; and what added to the horror of such a circumstance was that their deaths were concealed for the purpose of sharing their allowance of provisions until chance and the offensiveness of a corpse directed a surgeon or someone who had authority in the ship to the spot where it lay."

Phillip's commission made him governor-in-chief, and captain-general over all New South Wales, which then meant from Cape York, in the extreme north of Australia, to the "south cape of Van Diemen's Land," then, of course, supposed to be part of the main continent. He was ordered to land at Botany Bay and there form the settlement, but was given a discretionary power to change the site, if he considered it unsuitable.

Recognizing the unsuitability of Botany Bay, Phillip, before all the ships of the first fleet were arrived, set out in an 1788 open boat to explore the coast; and so, sailing northward, entered that bay only mentioned by Cook in the words before quoted, "abrest of an open bay," and by Hawkesworth (writing in the first person as Cook) thus:—

"At this time" (noon May 6th, 1770) "we were between two and three miles from the land and abrest of a good bay or harbour, in which there appeared to be a good anchorage, and which I called Port Jackson."

Perhaps, when Phillip's boat passed between the north and south heads of Port Jackson, he exclaimed what has so often been repeated since: "What a magnificent harbour!" And so on the 26th January, 1788, Sydney was founded upon the shores of the most beautiful bay in the world.

Phillip's "eye for ground" told him that the shores of Port Jackson were a better site for a settlement than the land near Botany Bay, but he had no sooner landed his people than the need for better soil than Sydney afforded was apparent. Then began a series of land expeditions into the interior, in which, with such poor means as these pioneers possessed, the country was penetrated right to the foot of the Blue Mountains. The first governor, despite the slight foothold he had established at Sydney—little better such a home than the deck of a ship—persistently searched for good land, and before his five years of office had expired agricultural settlement was fairly under way.

On the seaboard, although he was almost without vessels (scarcely a decent open boat could be mustered among the possessions of the colonists), with the boats of the Sirius the coast was searched by Phillip in person as well as by his junior officers.

Major Ross, who commanded the Marines, and who was also lieutenant-governor, described the settlement thus:—

"In the whole world there is not a worse country than what we have yet seen of this. All that is contiguous to us is so very barren and forbidding, that it may with truth be said, 'Here nature is reversed, and if not so, she is nearly worn out'; for almost all the seed we have put in the ground has rotted, and I have no doubt it will, like the wood of this vile country, when burned or rotten turn to sand;"

Captain Tench, one of Ross' officers, wrote:—

"The country is very wretched and totally incapable of yielding to Great Britain a return for colonising it.... The dread of perishing by famine stares us in the face. 1792 The country contains less resources than any in the known world;"

and the principal surgeon, White, described the colony in these words:—

"I cannot, without neglect of my duty to my country, refrain from declaring that if a 'favourable picture' has been drawn, it is a 'gross falsehood and a base deception.'"

Yet shortly before Phillip left it, in 1792, Collins says:—

"In May the settlers were found in general to be doing very well, their farms promising to place them shortly in a state of independence of the public stores in the articles of provisions and grain. Several of the settlers who had farms at or near Parramatta, notwithstanding the extreme drought of the season preceding the sowing of their corn, had such crops that they found themselves enabled to take off from the public store some one, and others two convicts, to assist in preparing their grounds for the next season."

In June, according to the same authority, the ground sown with wheat and prepared for maize was of sufficient area, even if the yield per acre did not exceed that for the previous season, to produce enough grain for a year's consumption.

The last returns relating to agriculture, prepared before Phillip left, show that the total area under cultivation was 1540 acres, and the previous year's returns show that the area had doubled as a result of the year's work. Besides this, considerable progress had been made with public buildings; and the convict population, which by the arrival of more transports had now reached nearly 4000 souls, were slowly but surely settling down as colonists.

With a thousand people to govern, in the fullest meaning of the word, and a desolate country, absolutely unknown to the exiles, to begin life in, Phillip's work was cut out. But, more than this, the population was chiefly composed of the lowest and worst criminals of England; famine constantly stared the governor in the face, and his command was increased by a second and third fleet of prisoners; storeships, when they were sent, were wrecked; many of Phillip's subordinates did their duty indifferently, often hindered his work, and persistently recommended the home Government to abandon the attempt to colonize. Sum up these difficulties, remember that they were bravely and uncomplainingly overcome, and the character of Phillip's administration can then in some measure be understood.

With the blacks the governor soon made friends, and such moments as Phillip allowed himself for leisure from the care of his own people he chiefly devoted in an endeavour to improve the state of the native race.

As soon as the exiles were landed he married up as many of his male prisoners as could be induced to take wives from the female convicts, offered them inducements to work, and swiftly punished the lazy and incorrigible—severely, say the modern democratic writers, but all the same mildly as punishments went in those days.

When famine was upon the land he shared equally the short commons of the public stores; and when "Government House" gave a dinnerparty, officers took their own bread in their pockets that they might have something to eat.

As time went on he established farms, planned a town of wide, imposing streets (a plan afterwards departed from by his successors, to the everlasting regret of their successors), and introduced a system of land grants which has ever since formed the basis of the colony's land laws, although politicians and lawyers have too long had their say in legislation for Phillip's plans to be any longer recognizable or the existing laws intelligible.1

The peculiar fitness of Phillip for the task imposed on him was, there is little doubt, due largely to his naval training, and no naval officer has better justified Lord Palmerston's happily worded and well-deserved compliment to the profession, "Whenever I want a thing well done in a distant part of the world; when I want a man with a good head, a good heart, lots of pluck, and plenty of common-sense, I always send for a captain of the navy."

A captain of a man-of-war then, as now, began at the bottom of the ladder, learning how to do little things, picking up such knowledge of detail as qualified him to teach others, to know what could be done and how it ought to be done. In all professions this rule holds good, but on shipboard men acquire something more. On land a man learns his particular business in the world; at sea his ship is a man's world, and on the completeness of the captain's knowledge of how to feed, to clothe, to govern, his people depended then, and in a great measure now depends, the comfort, the lives even, of seamen. So that, being trained in this self-dependence—in the problem of supplying food to men, and in the art of governing them, as well as in the trade of sailorizing—the sea-captain ought to make the best kind of governor for a new and desolate country. If your sea-captain has brains, has a mind, in fact, as well as a training, then he ought to make the ideal king.

Phillip's despatches contain passages that strikingly show his peculiar qualifications in both these respects. His capacity for detail and readiness of resource were continually demonstrated, these qualifications doubtless due to his sea-training; his sound judgment of men and things, his wonderful foresight, which enabled him to predict the great future of the colony and to so govern it as to hold this future ever in view, were qualifications belonging to the man, and were such that no professional training could have given.

Barton, in his History of New South Wales from the Records, incomparably the best work on the subject, says: "The policy of the Government in his day consisted mainly of finding something to eat." This is true so far as it goes, but Barton himself shows what finding something to eat meant in those days, and Phillip's despatches prove that, although the food question was the practical every-day problem to be grappled with, he, in the midst of the most harassing famine-time, was able to look beyond when he wrote these words: "This country will yet be the most valuable acquisition Great Britain has ever made."

In future chapters we shall go more particularly into the early life of the colony and see how the problems that harassed Phillip's administration continued long after he had returned to England; we shall then see how immeasurably the first governor was superior to the men who followed him. And it is only by such comparison that a just estimate of Phillip can be made, for he was a modest, self-contained man, making no complaints in his letters of the difficulties to be encountered, making no boasts of his success in overcoming them. The three sea-captains who in turn followed him did their best to govern well, taking care in their despatches that the causes of their non-success should be duly set forth, but these documents also show that much of their trouble was of their own making. In the case of Phillip, his letters to the Home Office show, and every contemporary writer and modern Australian historian proves, that in no single instance did a lack of any quality of administrative ability in him create a difficulty, and that every problem of the many that during his term of office required solution was solved by his sound common-sense method of grappling with it.

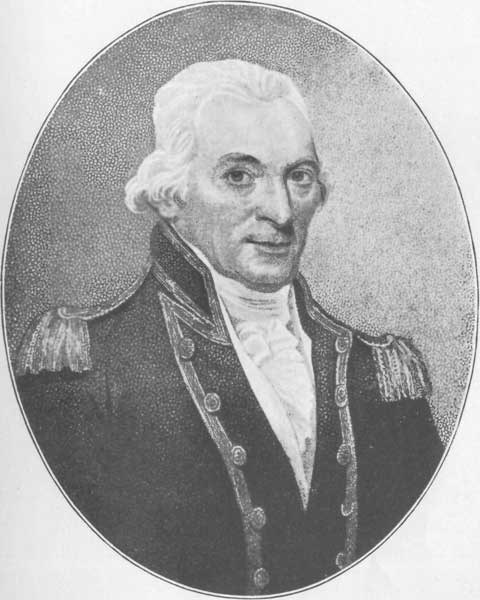

He was wounded by the spear of a black, thrown at him in a misunderstanding, as he himself declared, and he would not allow the native on that account to be punished. This wound, the hard work and never-ending anxiety, seriously injured the governor's health. He applied for leave of absence, and when he left the colony had every intention of returning to continue his work, but his health did not improve enough for this. The Government accepted his resignation with regret, and appointed him to the command of the Swiftsure, with a special pension for his services in New South Wales of £500 a year; in 1801 he was promoted Rear-Admiral of the Blue, in 1804 Rear-Admiral of the White, in 1805 Rear-Admiral of the Red, in 1809 Vice-Admiral of the White, and on July 31st, 1810, Vice-Admiral of the Red.

He died at Bath on August 31st, 1814, and was buried in Bathampton Church. For many years those interested in the subject, especially the New South Wales Government, spent much time in searching for his burial-place, which was only discovered by the Vicar of Bathampton, the Rev. Lancelot J. Fish, in December, 1897, after long and persistent research.

Those by whom the services of the silent, hard-working, and self-contained Arthur Phillip are least appreciated are, curiously enough, the Australian colonists; and it was not until early in 1897 that a statue to him was unveiled in Sydney. At this very time, it is sad to reflect, his last resting-place was unknown. Phillip, like Cook, did his work well and truly, and his true memorial is the country of which he was practically the founder.

CHAPTER V.

GOVERNOR HUNTER

Admiral Phillip's work was, as we have said, the founding of Australia; that of Hunter is mainly important for the service he did under Phillip. From the time he assumed the government of the colony until his return to England, his career showed that, though he had "the heart of a true British sailor," as the old song says, he somewhat lacked the head of a governor.

John Hunter was born at Leith in 1737, his father being a well-known shipmaster sailing out of that port, while his mother was of a good Edinburgh family, one of her brothers having served as provost of that city. Young Hunter made two or three voyages with his father at an age so young that when shipwrecked on the Norwegian coast a peasant woman took him home in her arms, and seeing what a child he was, put him to bed between two of her daughters.

He had an elder brother, William, who gives a most interesting account of himself in vol. xii. of the Naval Chronicle (1805). William saw some very remarkable service in his forty-five years at sea in the royal and merchant navies. Both brothers knew and were friendly with Falconer, the sea-poet, and John was shipmate in the Royal George with Falconer, who was a townsman of theirs. The brothers supplied many of the particulars of the poet's life, written by Clarke, and the name Falconer in connection with both Hunters often occurs in the Naval Chronicle.

After Hunter, senior, was shipwrecked, John was sent to his uncle, a merchant of Lynn, who sent the boy to school, where he became acquainted with Charles Burney, the musician. Dr. Burney wanted to make a musician of him, and Hunter was nothing loth, but the uncle intended the boy for the Church, and sent him to the Aberdeen University. There his thoughts once more turned to the sea, and he was duly entered in the Grampus as captain's servant in 1754, which of course means that he was so rated on the books in the fashion of the time. After obtaining his rating as A.B., and then as midshipman, he passed his examination as lieutenant in February, 1760; but it was not until twenty 1760 years later, when he was forty-three, that he received his lieutenant's commission, having in the interval served in pretty well every quarter of the globe as midshipman and master's mate. In 1757 he was under Sir Charles Knowles in the expedition against Rochefort; in 1759 he served under Sir Charles Saunders at Quebec; in 1756 he was master of the Eagle, Lord Howe's flagship, so skilfully navigating the vessel up the Delaware and Chesapeake and in the defence of Sandy Hook that Lord Howe recommended him for promotion in these words:—

"Mr. John Hunter, from his knowledge and experience in all the branches of his profession, is justly entitled to the character of a distinguished officer."

It was some years, however, before Hunter was given a chance, which came to him when serving in the West Indies, under Sir George Rodney, who appointed him a lieutenant, and the appointment was confirmed by the Admiralty.

In 1782 he was again under Lord Howe as first lieutenant of the Victory, and soon after was given the command of the Marquis de Seignelay. Then came the Peace of Paris, and Hunter's next appointment was to the Sirius. There is very little doubt from a study of the Naval Chronicle's biographies and from the letters of Lord Howe that, if that nobleman had had his way, Hunter would have been the first governor of New South Wales, and it is equally likely that, if Hunter had been appointed to the chief command, the history of the expedition would have had to be written very differently, for brave and gallant as he was, he was a man without method.

When Phillip was appointed to govern the colonizing expedition and to command the Sirius, Hunter was posted as second captain of the frigate, in order that the ship, when Phillip assumed his shore duties, should be commanded by a post-captain. A few days after the arrival of the fleet Hunter set to work, and in the ship's boats thoroughly surveyed Port Jackson. He was a keen explorer, and besides being one of the party who made the important discovery of the Hawkesbury river, he charted Botany and Broken Bays; and his charts as well as land maps, published in a capital book he wrote giving an account of the settlement, show how well he did the work.2

In September, 1788, Hunter sailed from Port Jackson for the Cape of Good Hope, to obtain supplies for the half-starving colony. On the voyage he formed the opinion that New Holland was separated from Van Diemen's Land by a strait, an opinion to be afterwards confirmed in its accuracy by Bass.

The poor old Sirius came in for some bad weather on the trip, and a glimpse of Hunter's character is given to us in a letter written home by one of the youngsters (Southwell) under him, who tells us that Hunter, knowing the importance of delivering stores to the half-famished settlers, drove the frigate's crazy old hull along so that—

"we had a very narrow escape from shipwreck, being driven on that part of the coast called Tasman's Head in thick weather and hard gales of wind, and embay'd, being twelve hours before we got clear, the ship forced to be overpressed with sail, and the hands kept continually at the pumps, and all this time in the most destressing anxiety, being uncertain of our exact situation and doubtful of our tackling holding, which has a very long time been bad, for had a mast gone, or topsail given way, there was nothing to be expected in such boistrous weather but certain death on a coast so inhospitable and unknown. And now to reflect, if we had not reached the port with that seasonable supply, what could have become of this colony? 'Twould have been a most insupportable blow, and thus to observe our manifold misfortunes so attemper'd with the Divine mercy of these occasions seems, methinks, to suggest a comfortable lesson of resignation and trust that there are still good things in store, and 'tis a duty to wait in a moderated spirit of patient expectation for them. 'Tis worthy of remark, the following day (for we cleared this dreaded land about 2 in the morning, being April the 22nd, 1789), on examining the state of the rigging, &c., some articles were so fearfully chafed that a backstay or two actually went away or broke."

Soon after came the end of the old ship. She had been sent to Norfolk Island, with a large proportion of the settlers at Port Jackson, to relieve the strain on the food supply. The contingent embarked with a marine guard under Major Ross in the Sirius and the Government brig Supply, and sailed on the 6th of March, 1790. Young Southwell, the signal midshipman stationed at the solitary look-out on the south head of Port Jackson, shall tell the rest of the story:—

"Nothing more of these [the two ships] were seen 'till April the 5th, when the man who takes his station there at daybreak soon came down to inform me a sail was in sight. On going up I saw her coming up with the land, and judged it to be the Supply, but was not a little surprised at her returning so soon, and likewise, being alone, my mind fell to foreboding an accident; and on going down to get ready to wait on the gov'r I desired the gunner to notice if the people mustered thick on her decks as she came in under the headland, thinking in my own mind, what I afterwards found, that the Sirius was lost. The Supply bro't an account that on the 19th of March about noon the Sirius had, in course of loading the boats, drifted rather in with the land. On seeing this they of course endeavoured to stand off, but the wind being dead on the shore, and the ship being out of trim and working unusually bad, she in staying—for she would not go about just as she was coming to the wind—tailed the ground with the after-part of her keel, and, with two sends of the vast surf that runs there, was completely thrown on the reef of dangerous rocks called Pt. Ross. They luckily in their last extremity let go both anchors and stopper'd the cables securely, and this, 'tho it failed of the intention of riding her clear, yet caused her to go right stern foremost on the rocks, by which means she lay with her bow opposed to the sea, a most happy circumstance, for had she laid broadside to, which otherwise she would have had a natural tendency to have done, 'tis more than probable she must have overset, gone to pieces, and every soul have perish'd.

"Her bottom bilged immediately, and the masts were as soon cut away, and the gallant ship, upon which hung the hopes of the colony, was now a complete wreck. They [the Supply] brought a few of the officers and men hither; the remainder of the ships company, together with Captain Hunter, &c., are left there on acc't of constituting a number adequate to the provision, and partly to save what they possibly can from the wreck. I understand that there are some faint hopes, if favor'd with extraordinary fine weather, to recover most of the provision, for she carried a great quantity there on the part of the reinforcement. The whole of the crew were saved, every exertion being used, and all assistance received from the Supply and colonists on shore. The passengers fortunately landed before the accident, and I will just mention to you the method by which the crew were saved. When they found that the ship was ruined and giving way upon the beam right athwart, they made a rope fast to a drift-buoy, which by the surf was driven on shore. By this a stout hawser was convey'd, and those on shore made it fast a good way up a pine-tree. The other end, being on board, was hove taut. On this hawser was placed the heart of a stay (a piece of wood with a hole through it), and to this a grating was slung after the manner of a pair of scales. Two lines were made fast on either side of the heart, one to haul it on shore, the other to haul it on board. On this the shipwreck'd seated themselves, two or more at a time, and thus were dragged on shore thro' a dashing surf, which broke frequently over their heads, keeping them a considerable time under water, some of them coming out of the water half drowned and a good deal bruised. Captn. Hunter was a good deal hurt, and with repeated seas knock'd off the grating, in so much that all the lookers-on feared greatly for his letting go; but he got on shore safe, and his hurts are by no means dangerous. Many private effects were saved, the sea driving them on shore when thrown overboard, but 'twas not always so courteous. Much is lost, and many escaped with nothing more than they stood in."