All the Days of My Life: An Autobiography

The future is not a torture chamber nor a condemned cell nor a reformatory. Even if we do make our bed in hell, God is there, and light, and truth, and love are there; and effort shall follow effort, and goal succeed goal, until we reach the colossal wisdom and goodness of spiritual beings. “Yet,” and reincarnation has a yet, though many like myself are loth to entertain it; but this “yet” is better expressed in the following verses than I can frame it. No one can be the worse for considering the possibility they infer:

“If thou art base and earthly, then despair;Thou art but mortal, as the brute that falls.Birds weave their nests, the lion finds a lair,Man builds his halls,“These are but coverts from earth’s war and storm;Homes where our lesser lives take shape and breath.But if no heavenly man has grown, what formClothes thee at death?“And when thy meed of penalty is o’erAnd fire has burned the dross where gold is none,Shall separate life but wasted heretofore,Still linger on?“God fills all space – whatever doth offendFrom His unbounded Presence shall be spurned;Or deem’st thou, He should garner tares, whose endIs to be burned.“If thou wouldst see the Power that round thee sways,In whom all motion, thought, and life are cast,Know that the pure who travel heavenward ways,See God at last.”Further I press upon the young, not to be ashamed of their disposition to be sentimental or religious. It is the sentimental young men who conquer; it is the men steeped in religious thought and aspiration, who do things. Whatever the scientists may say, if we take the supernatural out of life, we leave only the unnatural. But science is the magical word of the day, and scientists too often profess to doubt, whether we have a soul for one life, not to speak of a multitude of lives. “There is no proof!” they cry. “No proof! No proof of the soul’s existence.” Neither is there any proof of the existence of the mind. But the mind bores tunnels, and builds bridges and conceived aviation. And the soul can re-create a creature of clay, and of the most animal instincts, until he reaches the colossal manhood of a Son of God. Religion is life, not science.

It is now the twenty-seventh of October, 1912, and a calm, lovely Sabbath. I have been quite alone for three weeks, and have finished this record in unbroken solitude and peace. Mary is in Florida, and Alice is in New York with her sister Lilly. Sitting still in the long autumn evenings, I have drawn the past from the eternity into which it had fallen, to look at it again, and to talk to myself very intimately about it; and I confess, that though it is the nature of the soul to adore what it has lost, that I prefer what I possess. Though youth and beauty have departed, the well springs of love and imagination are, in my nature, too deep to be touched by the frost of age. Nourished by the dews of the heart and the intellect they will grow sweeter and deeper and more refreshing to the end of my life; for the things of the soul and the heart are eternal.

I have lived among “things unseen” as well as seen, always nursing in my heart that sweet promise of the times of restitution. Neither is the fire of youth dead, it glows within, rather than flames without – that is all. And there is a freshness, all its own, reserved for the aged who have come uphill all the way, and at last found the clearer air, and serener solitudes of those heights, beyond the fret and stir of the restless earth.

I have told my story just as I lived it; told it with the utmost candor and truthfulness. I have exaggerated nothing, far from it. This is especially true as regards all spiritual experiences. I hold them far too sacred to be added to, or taken from. My life has been a drama of sorrow and loss, of change and labor, but God wrote it, and I would not change anything He ordained.

“I would not miss one sigh or tear,Heart pang, or throbbing brow.Sweet was the chastisement severe,And sweet its memory now.”For as my day, so has my strength been; not once, but always. There was an hour, forty-five years ago, when all the waves and billows of the sea of sorrow went over my head. Then He said to me, “Am I not sufficient?” And I answered, “Yes, Lord.” Has He failed me ever since? Not once. Always, the power, has come with the need.

Farewell, my friends! You that will follow me through the travail and labor of eighty years, farewell! I shall see very few of you face to face in this life, but somewhere – perhaps – somewhere, we may meet and know each other on sight. And if you find in these red leaves of a human heart, a word of strength, or hope, or comfort, that is my great reward. Again farewell! Be of good cheer. Fear not. (2 Esdras, 6:33.) There is hope and promise in the years to come.

I will now let the curtain fall over my past, with a grateful acknowledgment that every sorrow has found its place in my life, and I should have been a loser without it. Even chance acquaintances have had their meaning, and done their work, and the web of life could not have been better woven of love alone.

God has not spoken His last word to me, though I am nearly eighty-one years old. When I have rested my eyes, I am ready for the work, ready for me. And I do not feel it too late, to offer daily the great prayer of Moses for consolation, “Comfort us again, for the years wherein we have seen evil.” As for the cares and exigencies of daily life, I commit them to Him, who has never yet failed me, and

“If I should let all other comfort go,And every other promise be forgot,My soul would sit and sing, because I knowHe faileth not!“He faileth not! What winds of God may blow,What safe or perilous ways may be my lot,Gives but little care; for this I know,He faileth not!”Sustained by this confidence, I can face without fear the limitations of age, and the transition we call death. I have love and friendship around me; I give help and sympathy whenever I can, and I do my day’s work gladly. The rest is with God.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX I

HUDDLESTON LORDS OF MILLOMIf I followed my own desire, instead of the general custom, I should place the genealogical history of the Huddlestons of Millom before my own story and not after it. For to the noble men and women who passed on the name to me, I owe everything that has made my life useful to others, and happy to myself. They conserved for me, upon the wide seas of the world and the mountains and fells of Cumberland, that splendid vitality, which still at eighty-two years of age enables me to do continuously eight and nine hours of steady mental work without sense of fatigue, which keeps me young in heart and brain and body. They transmitted to me their noble traditions of faith in God, and of passionate love for their country. From them I received that eternal hope which treads disaster under its feet, that courage which never fails, because God never can fail, and that natural religious trust which is the abiding foundation of a life that has continually turned sorrow into joy and apparent failure into certain success.

I honor all my predecessors as I honor my father and my mother, and I have had the promise added to that commandment. “My days have been long in the land which the Lord, my God, has given me.” These few natal notes are all I now know of them, but I have a sure faith that in some future the bare facts will grow into the living romances they only now hint of. I shall know them all and all of them will know me; and we shall talk together of the different experiences we met on our widely different roads to the same continuing home – a home not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.

A. E. B.HUDDLESTON LORDS OF MILLOMThe pedigree of this very ancient family is traced back to five generations before the Conquest. The first, however, of the name who was lord of Millom was,

Sir John Huddleston, Knight, who was the son of Adam, son of John, son of Richard, son of Reginald, son of Nigel, son of Richard, son of another Richard, son of John, son of Adam, son of Adam de Hodleston in co. York. The five last named according to the York MS were before the Conquest.

Sir John de Hodleston, Knight, in the year 1270 was witness to a deed in the Abbey of St. Mary in Furness. By his marriage with the Lady Joan, Sir John became lord of Anneys in Millom. In the 20th Edward I, 1292, he proved before Hugh Cressingham, justice itinerant, that he possessed JURA REGALIA within the lordship of Millom. In the 25th, 1297, he was appointed by the king warder or governor of Galloway in Scotland. In the 27th, 1299, he was summoned as baron of the realm, to do military service; in the next year, 1300, he was present at the siege of Carlaverock. In the 29th, 1301, though we have no proof that he was summoned, he attended the Parliament in Lincoln, and subscribed as a baron the celebrated letter to the Pope, by the title of lord of Anneys. He was still alive in the 4th of Edward IV, 1311. Sir John had three sons – John who died early, and Richard and Adam.

The Hudlestons of Hutton – John – were descended from a younger branch of the family at Millom, as were the Hudlestons of Swaston co., Cambridge, who settled there temp. Henry VIII, in consequence of a marriage with one of the co-heiresses of the Marquis Montague.

Richard Hudleston, son and heir, succeeded his father. Both he and his brother Adam are noticed in the later writs of Edward I. They were both of the faction of the Earl of Lancaster, and obtained in the 7th Edward II, 1313, a pardon for their participation with him in the death of the king’s favorite, Gaveston. Adam was taken prisoner with the earl in the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322, where he bore for arms gules fretted with silver, with a label of azure. Richard was not at that battle and in the 19th of the king, 1326, when Edward II summoned the Knights of every county to the Parliament at Westminster, was returned the first among the Knights of Cumberland. He married Alice, daughter of Richard Troughton in the 13th, Edward II, 1319-1320, and had issue.

John Hudleston, son of the above named Richard, who succeeded his father in 1337, and married a daughter of Henry Fenwick, lord of Fenwick, co. of Northumberland.

Richard Hudleston, son of John.

Sir Richard Hudleston, Knight, served as a banneret at the Battle of Agincourt, 1415. He married Anne, sister of Sir William Harrington K. G., and served in the wars in France, in the retinue of that knight.

Sir John Hudleston, Knight, son of Richard, was appointed to treat with the Scottish commissioners on border matters in the 4th Edward IV, 1464; was knight of the shire in the 7th, 1467; appointed one of the conservators of the peace on the borders in the 20th, 1480; and again in the 2nd of Richard, 1484; and died on the 6th of November in the 9th of Henry VII, 1494. He married Joan, one of the co-heirs of Sir Miles Stapleton of Ingham in Yorkshire. He was made bailiff and keeper of the king’s woods and chases in Barnoldwick, in the county of York; sheriff of the county of Cumberland, by the Duke of Gloucester for his life steward of Penrith, and warden of the west marches. He had three sons —

1. Sir Richard K. B., who died in the lifetime of his father, 1st Richard III. He married Margaret, natural daughter of Richard Nevill, earl of Warwick, and had one son and two daughters, viz:

Richard married Elizabeth, daughter of Lady Mabel Dacre, and died without issue, when the estates being entailed passed to the heir male, the descendant of his Uncle John.

Johan married to Hugh Fleming, Esq., of Rydal.

Margaret married to Launcelot Salkeld, Esq., of Whitehall.

2. Sir John.

3. Sir William.

Sir John Hudleston, second son of Sir John and Joan his wife, married Joan, daughter of Lord Fitz Hugh, and dying the 5th Henry VIII, 1513-1514, was succeeded by his son.

Sir John Hudleston K. B., espoused firstly the Lady Jane Clifford, youngest daughter of Henry, earl of Cumberland, by whom he had no issue. He married secondly Joan, sister of Sir John Seymour, Kn’t, and aunt of Jane Seymour, queen consort of Henry VIII, and by her he had issue —

Anthony his heir.

Andrew, who married Mary, sister and co-heiress of Thomas Hutton, Esq., of Hutton – John, from whom descended the branch at that mansion.

A daughter who married Sir Hugh Askew, Kn’t, yeoman of the cellar to Henry VIII, and Ann, married to Ralph Latus, Esq., of the Beck.

Sir John, died 38th, Henry VIII, 1546-7.

Anthony Hudleston, Esq., son and heir, married Mary, daughter of Sir William Barrington, Knight, and was succeeded by his son

William Hudleston, Esq., knight of the shire in the 43rd Elizabeth, who married Mary, daughter of Bridges, Esq., of Gloucestershire.

Ferdinando Hudleston, son and heir, was also knight of the shire in the 21st James I. He married Jane, daughter of Sir Ralph Grey, knight of Chillingham, and had issue nine sons – William, John, Ferdinando, Richard, Ralph, Ingleby, Edward, Robert, and Joseph; all of whom were officers in the service of Charles I. He was succeeded by his eldest son.

Sir William Hudleston, a zealous and devoted royalist, who raised a regiment of horse for his sovereign, and also a regiment of foot; the latter he maintained at his own expense during the whole of the war. For his good services and his personal bravery at the battle of Edgehill, where he retook the royal standard, he was made a knight banneret by Charles I on the field. He married Bridget, daughter of Joseph Pennington, Esq., of Muncaster. He had issue, besides his successor, a daughter, Isabel, who married Richard Kirkby, Esq., of Furness, and was succeeded by his son.

Ferdinand Hudleston, Esq., who married Dorothy, daughter of Peter Hunley, merchant of London, and left a sole daughter and heiress Mary, who married Charles West, Lord Delawar, and died without issue. At his decease the representation of his family reverted to

Richard Hudleston, Esq., son of Colonel John Hudleston, Esq., second son of Ferdinando Hudleston, and Jane Grey his wife. This gentleman married Isabel, daughter of Thomas Hudleston, Esq., of Bainton, co. York, and was succeeded by his son,

Ferdinando Hudleston, Esq., who married Elizabeth, daughter of Lyon Falconer, Esq., co. Rutland, by whom he had issue,

William Hudleston, Esq. This gentleman married Gertrude, daughter of Sir William Meredith, Bart., by whom he had issue, two daughters, Elizabeth and Isabella. Elizabeth, the elder, married Sir Hedworth Williamson, Bart., who in 1774 sold the estate for little more than 20,000 pounds to Sir James Lowther, Bart. – by whom it was devised to his successor, the Earl of Lonsdale.

Millom Castle, considerable remains of which are still in existence, is pleasantly situated in the township of Millom Below, near the mouth of the Duddon. It was fortified and embattled in 1335 by Sir John Hudleston, who obtained a license from the King for that purpose. In ancient times it was surrounded by a fine park. Here for many centuries the lords of Millom held their feudal pomp and state undisturbed by war’s tempestuous breath, from which the more northerly parts of the country suffered so severely, and so often; and we do not hear that the Castle was ever attacked previous to the wars of the Parliament, when it appears to have been invested, though no particulars respecting the occurrence have been recorded. It is at this period that the old vicarage house, which was in the neighborhood of the Castle, was pulled down, lest the rebels should take refuge therein. Mr. Thomas Denton tells us, that in 1688 the castle was much in want of repair. He also informs us that the gallows where the lords of Millom exercised their power of punishing criminals with death stood on a hill near the castle, and that felons had suffered there shortly before the time at which he was writing. He describes the park as having within twenty years abounded with oak, which to the value of 4,000 pounds had been cut down to serve as fuel at the iron forges. When John Denton wrote the castle appears to have been in a partly ruinous state, although the lords still continued to reside there occasionally. In 1739 the old fortress appears to have been in much the same condition as it is in our own times. In 1774 when Nicholson and Burn published their history, the park was well stocked with deer, and this state of things continued till the year 1802, when it was disparked by the earl of Lonsdale. The old feudal stronghold of the Boyvilles and Hudlestons now serves as a farmhouse, the principal part remaining is a large square tower, formerly embattled, but at present terminated by a plain parapet. The chief entrance appears to have been in the east front by a lofty flight of steps. In a wall of the garden are the arms of Hudleston, as also in the wall of an outhouse. On the south and west sides traces of the moat are still visible. The lordship of Millom still retains its own coroner.

After the sale of Millom to the Earl of Lonsdale, which occurred only twenty-five years before the birth of my father, many of the Huddleston family emigrated to Newfoundland and to the American colonies. There were Huddlestons settled in Texas who had fought with General Sam Houston. They were large land owners and had patriarchal wealth in cattle and horses. I know this, for I wrote their assessments during the last two years of the Civil War. A California editor told me three years ago that there were Huddlestons among the rich miners of that state; and there is a notable branch of the family descended from Valentine Huddleston who came to the Plymouth colony in A.D. 1622. This gentleman is among the list of the proprietors of Dartmouth. He had two sons the eldest of whom bore the family name of Henry. Nothing can be more clear and straight than the pedigree of this branch; and its direct descendant is at the present day one of New York’s most esteemed and influential citizens.

THE LORDS OF MILLOMFrom Bulmer & Co.’s “History and Directory of Westmoreland,” Millom Parish, page 154The Boyvilles held the seigniory in heir male issue from the reign of Henry I to the reign of Henry III, a space of one hundred years, when the name and family ended in a daughter, Joan de Millom, by her marriage with Sir John Huddleston (No. 5, Foot-Prints), conveyed the inheritance to that family, with whom it remained for about five hundred years. The Huddlestons were an ancient and honorable family who could trace their pedigree back five generations before the Conquest. The lords of Millom frequently played important parts in the civil and military history of the country. Richard and Adam (Nos. 6 and 7, Foot-Prints), reign of Edward II, were implicated in the murder of Gaveston, the king’s favorite, and the latter was taken prisoner at the battle of Borough Bridge in 1322. Sir Richard Huddleston (No. 12, Foot-Prints) served as a banneret at the battle of Agincourt in 1415. Sir John Huddleston was appointed one of the conservators of the peace on the borders in 1480, high sheriff of Yorkshire, steward of Neurith, and warden of the West Marches.

Sir William Huddleston (No. 17, Foot-Prints), a zealous and devoted royalist, raised a regiment of horsemen for the service of the sovereign, as also a regiment of footmen, and the latter he maintained at his own expense. At the battle of Edge Hill he retook the standard from the Cromwellians, and for this act of personal valor he was made a knight banneret by the king on the field.

William Huddleston (not No. 17, Foot-Prints), the twenty-first of his family who held Millom, left two daughters, Elizabeth and Isabella. The former of whom married Sir Hedworth Williamson, Bart., who in 1774 sold the estate for a little more than £20,000 to Sir James Lowther, Bart., from whom it has descended to the present Earl of Lonsdale.

Millom Castle, of which considerable remains are still in existence, is pleasantly situated near the church. It was for many centuries the feudal residence of the lords of Millom, and though its venerable ruins have been neglected, still they point out its former strength and importance. It was fortified and embattled in 1335 by Sir John Huddleston in pursuance of a license received from the king. It was anciently surrounded by a park well stocked with deer, and adorned with noble oaks, which were cut down in 1690 by Ferdinando Huddleston to supply timber for the building of a ship and fuel for his smelting furnace.

The principal part of the castle now remaining is a large square tower formerly embattled but now terminated by a plain parapet.

Mr. John Denton tells us the Castle in his time (the middle of the 15th century) was partly in a ruined state though the lords continued to reside there occasionally. Before the year 1774 the park was well stocked with deer and continued so until 1802 when Lord Lonsdale disparked it and 207 deer were killed and the venison sold from 2d. to 4d. per lb.

The feudal hall of the Boyvilles and the Huddlestons where the lords of Millom lived in almost royal state is now the domicil of a farmer. Sic transit gloria mundi.

The moat is still visible in one or two places and in a wall and also in the garden may be seen the arms of the Huddlestons.

The castle is now undergoing reparation; some new windows are being inserted and additional buildings are being erected.

(We are indebted to Miss Alethia M. Huddleston, of Lancashire, England, for the copy of the foregoing valuable account of Millom.)

APPENDIX II

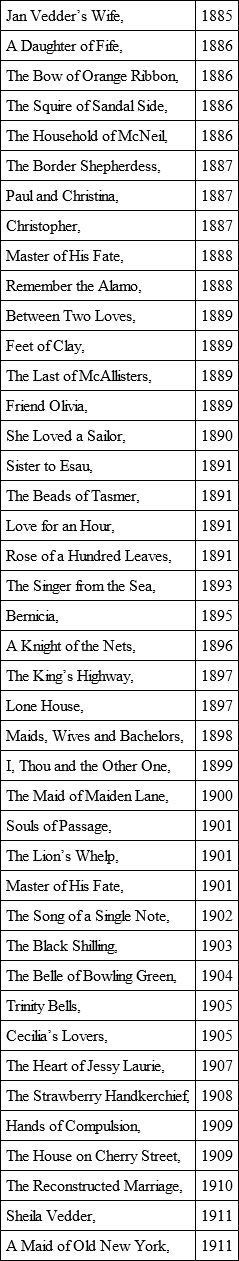

BOOKS PUBLISHED BY DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

APPENDIX III

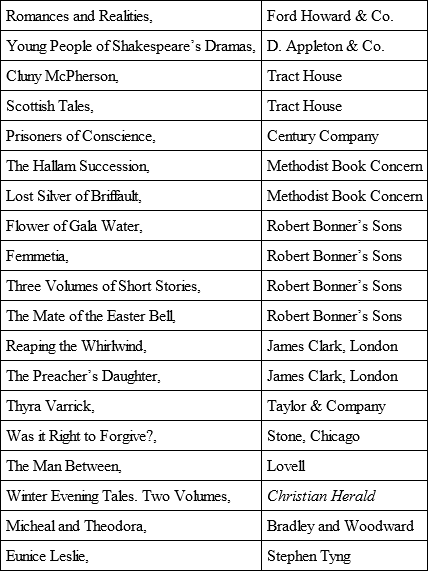

BOOKS PUBLISHED BY OTHER PUBLISHERS

This list includes none of the short stories written every week for Robert Bonner’s Ledger; none written very constantly in the early years of my work for the Christian Union, the Illustrated Christian Weekly, Harper’s Weekly, Harper’s Bazaar, Frank Leslie’s Magazine, the Advance and various other papers. Nor yet does it include any of the English papers or syndicates for which I wrote; nor yet the poem written every week for fifteen years for the Ledger; nor the poems written very frequently for the Christian Union, the Independent, the Advance, daily papers, and so forth. Nor can I even pretend to remember the very numerous essays, and social and domestic papers which were almost constantly contributed; I have forgotten the very names of this vast collection of work and I never kept any record of it. Indeed, only some chance copy has escaped the oblivion to which I gave up the rest. They kept money in my purse; that was all I asked of them. I do not even possess a full set of the sixty novels I have written. I may have twenty or thirty, not more certainly.

From among the hundreds of poems I have written during forty years I have saved enough to make a small volume which some day I may publish. But I never considered myself a poetess in any true sense of the word. “The vision and faculty divine” was not mine; but I had the most extraordinary command of the English language and I could easily versify a good thought, and tune it to the Common Chord – the C Major of this life. Women sang my songs about their houses, and men at their daily work and some of them went all around the world in the newspapers. “The Tree God Plants, No Wind Can Hurt,” I got in a Bombay paper; and “Get the Spindle and Distaff Ready, and God Will Send the Flax,” came back to me in a little Australian weekly. And for fifteen years I made an income of a thousand dollars, or more, every year from them. So, if they were not poetry they evidently “got there!” From among the few saved I will print half a dozen. They will show what “the people” liked, and called poetry.

I must here notice, that I used two pen names as well as my own. I never could have sold all the work I did under one name. But to my editors, the secret was an open one; and until the necessity for it was long past, not one of them ever named the subterfuge to me. That was a very delicate kindness and it pleases me to acknowledge it. Some of my very best work was done under fictitious names. Truly I got no credit for it, but I got the money, and the money meant all kinds of happiness.