An Old English Home and Its Dependencies

All this is of the past, and so also is the throb of the flail. There are not many labourers now who understand how to wield the flail. The steam thrasher travels from farm to farm and thrashes and winnows, relieving man of the labour. The flail is only employed for the making of "reed," i. e., straw for thatching the rick.

What a robust, rubicund, hearty fellow is our old English farmer. The breed is not extinct, thank God! At one time, when it was the fashion to run two and three farms into one, and let this conglomerate to a man reputed warm and knowing, then it did seem as if the "leather pocketed" farmer was doomed to extinction. But it is the gentleman farmer who has gone to pieces, and the simple old type has stood the brunt of the storm, and has weathered the bad times.

What a different man altogether he is from the French paysan and the German bauer! The latter, among the mountains, is a fine specimen, his wealth is in oxen and cows. But the bauer, on arable land in the plains, is an anxious, worn man, who falls into the hands of the Jews, almost inevitably. Our farmers, well fed, open-hearted, hospitable, yet close-fisted over money, would do well to learn a little thrift from the continental peasant. On market days, if they sell and buy, they also spend a good deal at the ordinary and in liquor.

At a tythe dinner I gave, in another part of England from that I now occupy, the one topic of conversation and debate was whether it were expedient on returning from market to tumble into the ditch or into the hedge, and if it should happen that the accident happened in the road, at what portion of the highway it was "plummest" to fall.

On market days is the meeting of the Board of Guardians, and on that Board the farmer exercises authority and rules.

An old widow in receipt of parish relief once remarked: "Our pass'n hev been preachin' this Michaelmas a deal about the angels bein' our guardgins. Lork a biddy! I've been in two counties, in Darset and Zummerset, as well as here. Guardgins be guardgins whereiver they be. And I knows very well, if them angels is to be our guardgins in kingdom come – it'll be a loaf and 'arf a crown and no more for such as we."

In North Devon there was a farmer, whom we will call Tickle, who was on a certain Board of Guardians, of which Lord P. was chairman. Now Mrs. Tickle died, and so for a week or two the farmer did not take his usual seat. The chairman got a resolution passed condoling with Mr. Tickle on his loss.

Next Board day, the farmer appeared, whereupon Lord P. addressed him: "It is my privilege, duty, and pleasure, Mr. Tickle, to convey to you, on behalf of your brother guardians, an expression of our sincere and heartfelt and profound regret for the sad loss you have been called on to endure. Mr. Tickle, the condolence that we offer you is most genuine, sir. We feel, all of us, that the severance which you have had to undergo is the most painful and supreme that falls to man's lot in this vale of tears. Mr. Tickle, it is at once a rupture of customs that have become habitual, a privation of an association the sweetest, holiest, and dearest that can be cemented on earth, and it is – it is – in short – it is – Mr. Tickle, we condole with you most cordially."

The farmer addressed looked about with a puzzled and vacant expression, then rubbed his chin, then his florid cheeks, and seemed thoroughly nonplussed. Presently a brother farmer whispered in his ear, "Tes all about the ou'd missus you've lost."

"Oh!" and the light of intelligence illumined his face, "that's it, es it. Well, my lord and genl'men, I thank y' kindly all the same, but my ou'd woman – her wor a terr'ble teasy ou'd toad. It hev plased the Lord to take 'er, and plase the Lord he'll keep 'er."

The ordinary farmer is not a reader – how can he be, when he is out of doors all day, and up in the morning before daybreak? We complain that he does not advance with the times; but he is a cautious man, who makes quite sure of his ground before he steps.

The County Council, at the expense of the ratepayers, send about lecturers, who are well paid, to hold forth in village schoolrooms on scientific agriculture, the chemistry of the soil, and scientific dairying.

No one usually attends these lectures except a few ladies, but on one occasion a farmer was induced by the rector or the squire, as a personal favour, to listen to one on the chemistry of common life.

He listened with attention when the lecturer described the constituents of the atmosphere, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen. At the close he stood up, stretched himself, and said: "Muster lecturer! You've told us a terr'ble lot about various soorts o' gins, oxegen and so on, I can't mind 'em all, but you ha'nt mentioned the very best o' all in my 'umble experience, and that's Plymouth gin. A drop o' that with suggar and water – hot – the last thing afore you go to bed, not too strong nor too weak neither, is the very first-ratedst of all. I've tried it for forty years."

And then he went forth, shrugged his shoulders, and said, "That chap, he's traveller for some spirit merchants, as have some new-fangled gins – but I'll stick to Plymouth gin, I will."

A friend of mine was Mayor for a year in a town, the name of which is unimportant. Being of a hospitable and kindly turn, he sent invitations to all the farmers in the neighbourhood who were within the purlieu of the borough to dine with him on a certain evening, and at the bottom of the invitation put the conventional R. S. V. P.

To his surprise he received no answers whatever. The invitation, however, was much discussed at the ordinary, and the mysterious letters at the close subjected to scrutiny and debate.

"Now what do you makes 'em out to mane?" asked one farmer.

"Well, I reckon," answered he who was addressed, "tes what we're to ate at his supper. Rump Steak and Veal Pie."

"Git out for a silly," retorted the first, "muster bain't sach a vule as to have two mates on table to once. Sure enough them letters stand for Rump Steak and Viggy (plum) Pudden'."

"Ah! Seth! you have it. That's the truth," came in assent from the whole table.

But what a fine man the old farmer is – the very type of John Bull. That he is being driven out of existence by foreign colonial competition I cannot believe. He is a slow man to accommodate himself to changed circumstances, but he can turn himself about when he sees his way; and he has a shrewd head, and knows soil and climate.

In George Coleman's capital play, "The Heir at Law," Lady Daberly says to her son Dick, "A farmer! – and what's a farmer, my dear?"

To which Dick replies, "Why, an English farmer, mother, is one who supports his family, and serves his country by his industry. In this land of commerce, mother, such a character is always respectable."

CHAPTER X.

Cottages

The type of the old English cottage was – one room below for kitchen and every other purpose by day, and one room upstairs for repose at night for the entire family, and this reached by a stair like a ladder. Very poor quarters as we now consider, but relatively not poor when compared with the farms and manor-houses at the time when they were built.

And a vast number of our labourers' cottages date from two, three, and four hundred years ago; especially where built of stone or "cob." The latter is kneaded clay with straw in it. This makes a warm and excellent wall, and one that will endure for ever if only the top be kept dry. Brick cottages are later. Timber and plaster belong to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The oak turns hard as iron and is perhaps more enduring than iron, for the latter is eaten through in time with rust.

That which is destroying the old cottage is not the tooth of time, but the insurance office, which imposes heavy rates on thatched buildings, and when the thatch goes and its place is taken by slate, the beauty of the cottage is gone. But generally, if a cottage that was thatched has to be slated, it is found that the timbers were not put up to bear the weight of slate, so have to be renewed, and then it is said by the agent, "Pull the whole thing down, it is not worth re-roofing. Build it afresh from the foundation." Then, in the place of a lovely old building with its windows under thatch, and the latter covering it soft and brown and warm as the skin of a mole, arises a piece of hideousness that is perhaps more commodious, but hardly so comfortable. I know that labourers who have been transferred from old "cob" cottages under thatch to new brick cottages under slate, complain bitterly that they are losers in coziness by the exchange, and that they suffer from cold in these trim and gaunt erections.

No cottages are more lovely than those that are tiled, when the tiles are old; and the Eastern Counties, if they lack the beauty of landscape of the West, and of the Welsh hills, and the Lake district, infinitely surpass them in the picturesqueness of their groups of cottages. Slate, it must be admitted, is only beautiful when mellowed by the growth over it of lichen; and some slate not even time can make other than ugly.

I have been reading Professor Fawcett's Economic Position of the British Labourer, and I note the following passage relative to our agricultural workmen: "Theirs is a life of incessant toil for wages too scanty to give them a sufficient supply even of the first necessaries of life. No hope cheers their monotonous career; a life of constant labour brings them no other prospect than that when their strength is exhausted they must crave as suppliant mendicants a pittance from parish relief. Many classes of labourers have still to work as long, and for as little remuneration as they received in past times; and one out of every twenty inhabitants of England is sunk so deep in pauperism that he has to be supported by parochial relief."

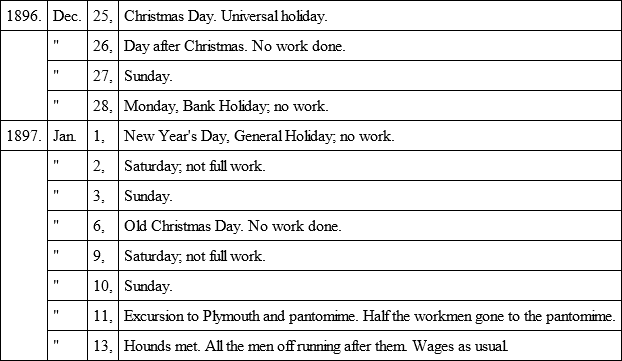

This is very interesting. Mr. Fawcett was, I believe, blind and resided in a town. No doubt he evolved this sad picture out of his interior consciousness. Beside it let me put some notes from my diary.

Ten work-days out of twenty. I don't grudge it them. I rejoice over it with all my heart, but I cannot see that this quite jumps with Professor Fawcett's description. Of course it is not Christmas time all the year, but at other times are other festivals, flower shows, reviews, harvest festivals, club feasts, Bank Holidays, regattas, etc., etc., and my experience is that when there is anything to be seen the workmen go to see it and take their wives with them.

A few years ago there was a large bazaar given in my neighbourhood. I asked afterwards of the secretary and treasurer from whom most money was taken. The answer was, "From the young agricultural workmen. Squires didn't come, farmers didn't come – all too poor; but the young farm lads and lasses seemed to have gold in their purses and not to mind spending it."

Very glad to hear it I was, only I regretted that it was one class only that was well off and not the other two.

Now let us see whether my experience of the wages and housing of the labourers agrees with Professor Fawcett's picture. Here, where I live – and it was the same when I was in other parts of England (before the depression there) – the wages of the labourer was fourteen to fifteen shillings a week. For a comfortable cottage with over half an acre of garden he pays from £4 to £6 per annum, hardly sufficient to pay for keeping the cottage in repair, consequently it may be said that he has garden and half the house rent given to him. The garden is worth to him from £4 to £6 per annum. Consequently his receipts per annum may be reckoned at £42 or £48. He has to pay out of this into his club. He has nothing to pay in rates or taxes, or for his children's education; and if he has children, every son, on leaving school, till he marries brings in to him say 6s. to 12s. per week for his board, and his daughters go out into service and earn from £10 to £20 per annum as wages, and ought to remit some of this to their parents.

I am convinced that there is many a peasant proprietor abroad who would jump at the offer to be an English farm labourer.

I have spent ten years in collecting the folk songs of the West of England, and I have not come across one in which the agricultural labourer grumbles at his lot. On the contrary, their songs, the very outpouring of their hearts, are full of joy and happiness. Once, indeed, an old minstrel did say to me, "Did y' ever hear, sir, 'The Lament of the Poor Man?'"

I pricked up my ears. Now at last I was about to hear some socialistic sentiment, some cry of anguish of the oppressed peasant. "No," I answered, "never – sing it me."

And then I heard it. The lament of a man afflicted with a scolding wife. That alone made him poor, and that affliction is not confined to the dweller in the cottage.

Here and there we do come on miserable cottages – a disgrace to the land. But to whom do they belong? They have been erected on lives, or by squatters, and the landlords have no power over them. I know a certain village which is nearly all ruinous; but there all the ruinous cottages are held on lives. It is quite true that the landowner can force the holder of the tenure to put it in repair, but he is reluctant to put on the screw of the law, and he argues, "The houses were built to last three lives – no more. When they fall in to me, they will fall in altogether, and I will build decent, solid cottages in their place."

Over the squatter's cottage he has no control whatever.

Listen to the note of the agricultural, downtrodden labourer, his wail of anguish under the heel of the squire and farmer.

"When the day's work is ended and over, he'll goTo fair or to market to buy him a bow,And whistle as he walks, O! and shrilly too will sing,There's no life like the ploughboy's all in merry spring."Good luck to the ploughboy, wherever he may be,A fair pretty maiden he'll take on his knee,He'll drink the nut-brown ale, and this song the lad will sing,O the ploughboy is happier than the noble or the king."This is sung from one end of England to another, and always to the same very rude melody in a Gregorian tone, that shows it has expressed the sentiments of the ploughboy for at least two hundred years.

Listen again:

"Prithee lend your jocund voices,For to listen we're agreed;Come sing of songs the choicest,Of the life the ploughboys leadThere are none that live so merryAs the ploughboy does in spring,When he hears the sweet birds whistleAnd the nightingales to sing."In the heat of the daytimeIt's little we can do,We will lie beside our oxenFor an hour, or for two.On the banks of sweet violetsI'll take my noontide rest,And it's I can kiss a pretty girlAs hearty as the best."O, the farmer must have seed, sirs,Or I swear he cannot sow,And the miller with his millwheelIs an idle man also.And the huntsman gives up hunting,And the tradesman stands aside,And the poor man bread is wanting,So 'tis we for all provide."That last verse is delicious. It lets us into the very innermost heart of the ploughman. He knows his own value – God bless him. And so do we.

There is one great advantage in our English system, that, not being bound to the soil, the poor workman can go wherever there is a demand for him. And this is one reason why we have so many examples of a young fellow who rises high up in the social scale, and from being a poor lad springs to be a rich man.

In another chapter I shall have something to say of the parish ne'er-do-weel. But if every parish has one of these latter, there is hardly one that cannot show his contrary. And now for a true story of one of these latter.

There is no country in the world, America possibly excepted, where greater facilities are afforded for a youth of energy and intelligence to make his way. But there is something more that gives a lad now a chance of rising, something far less generally diffused than intelligence and less conspicuous than energy, which is in immense demand, and at a premium – and that is honesty. In ancient Greece the churlish philosopher is said to have lit a lamp and gone about the streets by day looking for an honest man. It is, perhaps, the failing of advanced and widespread culture that it encourages mental at the expense of moral progress; nay, further, that with the development of mental advance there is moral retrogression. Every man is now in such a hurry to make himself comfortable that he loses all scruple as to the way in which he sets about it, and so misses the one way paramount over all others, that of common honesty.

This lack of integrity is the thing that all employers complain of. They can no longer repose trust in their workmen, in their clerks – all have to be watched. There is no question as to their abilities, only as to their honesty.

This leads me to tell the story – which is true – of a young man with whose career I am well acquainted, from childhood till he was prematurely cut off whilst in the ripeness of his powers, trusted, esteemed, and loved by all with whom he was brought in contact. He began life with little to favour him. His father was a quarryman who was killed by a fall of rock, and his mother died not long after, never having recovered from the shock of the loss of a dearly loved young husband. So the orphan boy was left to be brought up by his grandmother, a widow, who went out charing for her maintenance, and who received eighteen pence and a loaf per week from the parish, and who is alive to this day.

The lad grew up lanky, and looked insufficiently fed. The squire of the parish took him early into his service to clean boots and run errands at sixpence a day, and after a while, as the fellow proved trusty, advanced him to be a butler boy in the house, in livery, to clean knives and attend the door.

Trusty and good the lad remained in this condition also, but it was not congenial to him. One day the housemaid told the mistress, with a laugh, "Please, ma'am, what do you think? Every now and then I've found bits of wood laid one across another under Richard's bed. I couldn't make out what it meant, at last I've found out. He's made an arrangement with the gardener on certain mornings to be up very early before his regular work begins, that he may go round the greenhouses with him and help him there, and a bit in the gardens. Richard won't be a minute late for his work in the house, but he do so dearly love to be in the garden that he'll get up at four o'clock to go there, and as he's a heavy sleeper, he has the notion that if he makes a little cross under his bed by putting one stick across another, and says over it, 'I want to be waked at four o'clock,' then sure enough at that hour he will rise."

When his master and mistress knew the lad's taste, and heard from him how much happier he would be in the gardens than in the house, they put him with the gardener, and he laid aside his livery never to resume it.

In the gardens he remained for a good many years, always the same, reliable in every particular, and then an uneasiness became manifest in him. When he met his master he was embarrassed, as though he had something on his mind that he wished to say, and yet shrank from saying. Then the squire received a hint that Richard wished to "have a tell" with him in private, and he made occasion for this, and opened the way. The young man still had difficulties in bringing out what was in his heart, but at last it came forth. He thought he had learned all that could be learned from the head gardener; indeed, in several points, aided by books, the underling believed he knew more than his superior, who, however, was too conservative in his habits to yield his opinions and change his practice. Richard wished to better himself. It was not increase of wage that he desired, but opportunities of advance in knowledge. He had hesitated for long, because he knew that he owed so much to his master, who had been kind to him, and thought for him for many years. For this reason he did not wish to inconvenience him, yet he believed there were many other lads in the village capable of filling his place, and the desire in him to progress in his knowledge of flowers and fruit had become almost irresistible.

When the squire heard this, he smiled. "Richard," he said, "I have been thinking the same thing. I saw you were being held back, and that is what ought not to be done with any young mind. I have already written about you to Mr. Kewe, the great nurseryman, and if he values my opinion at all and consults his own interest, by the end of the week there will be a letter from him to engage you."

Mr. Kewe did consult his own interest, and secured this young man. Then, when Richard came to take his leave, and thank his master again for his help, with heightened colour he said, "I think, sir, I ought to add that you have made two young people happy."

"Two! Richard?"

"Yes, sir. There's Mary Kelloway; she has been brought up next door to grandmother and me, and somehow we have always thought of each other as like to be made one some day, and now that I see that I am going ahead in my profession, both Mary and I fancy the day isn't so terribly far off."

"Mary Kelloway!" exclaimed the squire, and did not at once congratulate the young man.

"Yes, sir, there is not a better girl in the place."

"I am quite aware of that, Richard, – but you know – "

"Yes, sir, I know that her father and brother died of decline, and that she is delicate herself; but, sir, her mother's very poor, and more's the reason I should marry her, for then she can have strengthening things other than Mrs. Kelloway can afford to give her."

"I am a little afraid, Dick, she will not make a strong or useful wife, though that she is as good as gold I do not doubt for an instant."

"More's the reason why I should work hard with both arms and head," answered the young gardener, "and that, sir, is one reason why I have been so set on getting forward in my profession."

Richard was for a few years with the great nursery gardener, Mr. Kewe, who speedily found that nothing advanced in his favour by the squire, his good customer, was unfounded. He entrusted more and more to Richard, and the latter rapidly acquired knowledge and experience.

Occasionally, when he was allowed a day off, he would run to his native village and see his grandmother, and, naturally, Mary Kelloway. But such holidays could not be frequently accorded, for his master knew he could trust Richard, and was doubtful whom else in his gardens he could trust, and plants require the most careful watching and tending. One day's neglect in watering, one night's frost unforeseen, may ruin hundreds of pounds' worth of goods. The thrip, the mealy bug, the scale, are enemies to be grappled with and fought with incessant vigilance, and the green fly with its legions coming none know whence, appearing at all seasons, must be combated with smoke and Gishurst's compound without intermission.

One day, about noon, or a little after, a stranger came into the nursery gardens, and entering one of the conservatories where was Richard, asked if he could see Mr. Kewe.

"The master," answered the young man, "is just now at his dinner. If it be particularly desired I could run to his house."

"By no means," interrupted the visitor. "I should like to have a walk round the grounds and through the houses, and I daresay you will be good enough to accompany me. I have an hour at my disposal, and I would rather spend it here than anywhere else. I will await the arrival of Mr. Kewe."

Accordingly Richard accompanied the visitor about the nursery, and told him the names of the plants, putting aside such as the stranger ordered or selected.

"I don't know how it is," said the latter, pointing with his stick to a row of flourishing rhododendrons, "but you and all my friends grow these to perfection, whilst there is a fatality with mine; they won't flower, or if they do, they throw out sickly bloom, and the plants continually die and have to be removed."

"It depends on the soil, sir. What is your soil?"

"I don't know. Most things do well. We are on chalk."

"That is it, sir. The rhododendron has an aversion to lime in any form. A man will not thrive on hay, nor a horse on mutton chops. Each plant has its own proper soil in which it thrives. Give it other soil and it languishes and dies. Excuse me, sir, for a moment."