По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

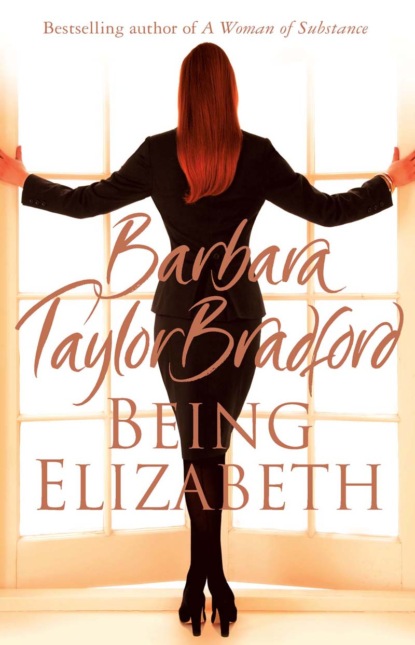

Being Elizabeth

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He shook his head, rendered mute for a split second.

The sun was streaming in through the windows, bathing her in shimmering light, and the vividness of her colouring was shown off to perfection – her glorious auburn hair shot through with gold, her perfect English complexion, so fair and milky white, and her finely-wrought features reminiscent of the Deravenels. She was the spitting image of both men; the only difference was her eyes. They were a curious grey-black, whilst Harry Turner’s and Edward Deravenel’s were the same sky blue.

‘What is it? You’re staring at me in the most peculiar way,’ said Elizabeth, and walked into the study, her expression one of puzzlement.

‘Three peas in a pod,’ Cecil answered with a faint laugh. ‘That’s what I was thinking as you stood there in the doorway. The sunlight was streaming in, and the marked resemblance between you and your father and great-grandfather was … uncanny.’

‘Oh.’ Elizabeth turned around, her eyes moving from the portrait of her father to the one of her great-grandfather, the famous Edward Deravenel, the father of Bess, her paternal grandmother. It was he she admired the most, he who had been the greatest managing director of all time, in her opinion … the man she hoped to emulate. He was her inspiration.

‘Well, yes, I guess we do look as if we’re related,’ she answered, her black eyes dancing mischievously. Taking a seat opposite Cecil, she went on, ‘Just let’s hope that I can accomplish what they did.’

‘You will.’

‘You mean we will.’

He inclined his head, murmured, ‘We’ll do our damnedest.’

Shifting slightly in the chair, Elizabeth focused her eyes on Cecil with some intensity, and said slowly, ‘What are we going to do about the funeral? It will have to be here, won’t it?’

‘No other place but here.’

‘Have you any ideas about who we ought to invite?’

‘Certainly members of the board. But under the circumstances, I thought it was a good idea to turn the whole thing over to John Norfell. He’s one of the senior executives, a long-time member of the board, and he was a friend of Mary’s. Who better than him to make all the arrangements? I spoke to him a short while ago.’

Elizabeth nodded, a look of relief on her face. ‘The family chapel holds about fifty, but that’s it. And I suppose we’ll have to feed them –’ She shook her head, sighing. ‘Don’t you think it should be held in the late morning, so that we can serve lunch afterwards and then get them out of here around three?’

Amused, Cecil began to chuckle. ‘I see you’ve already worked it out. And I couldn’t agree more. I hinted at something of the sort to Norfell, and he seemed to acquiesce. I doubt that anyone even really wants to come up here in the dead of winter.’

She laughed with him and pointed out, ‘It’s so cold. I put my nose outside earlier, and decided not to take a walk. God knows how my ancestors managed without central heating.’

‘Roaring fires,’ he suggested, and glanced at the one burning brightly in the study. ‘But to my way of thinking, fires wouldn’t have been enough … we’ve got the central heating at its highest right now, and it’s only comfortable.’

‘That’s one of the great improvements my father made, putting in the heating. And air conditioning.’ Rising, Elizabeth strolled over to the fireplace, threw another log on the fire, and then turning around, she said quietly, ‘What about the widower? Do we invite Philip Alvarez or not?’

‘It’s really up to you … but perhaps we should invite him. Out of courtesy, don’t you think? And look here, he was always well disposed towards you,’ Cecil reminded her.

Don’t I know it, she thought, remembering the way her Spanish brother-in-law had eyed her somewhat lasciviously and pinched her bottom when Mary wasn’t looking. Pushing these irritating thoughts to one side, she nodded. ‘Yes, we’d better invite him. We don’t need any more enemies. He won’t come though.’

‘You’re right about that.’

‘Cecil, how bad is it really? At Deravenels? We’ve touched on some of the problems these last couple of weeks, but we haven’t plunged into them, talked about them in depth.’

‘And we can’t, not really, because I haven’t seen the books. I haven’t worked there for four and a half years, and you’ve been gone for one year. Until we’re both installed, I won’t know the truth,’ he explained, and added, ‘One thing I do know though is that she gave Philip a lot of money for his building schemes in Spain.’

‘What do you mean by a lot?’

‘Millions.’

‘Pounds sterling or euros?’

‘Euros.’

‘Five? Ten million? Or more?’

‘More. A great deal more, I’m afraid.’

Elizabeth came back to the desk and sat down in the chair, staring at Cecil Williams. ‘A great deal more?’ she repeated in a low voice. ‘Fifty million?’ she whispered anxiously.

Cecil shook his head. ‘Something like seventy-five million.’

‘I can’t believe it!’ she exclaimed, a stricken look crossing her face. ‘How could the board condone that investment?’

‘I have no idea. I was told, in private, that there was negligence. Personally, I’d call it criminal negligence.’

‘Can we prosecute someone?’

‘She’s dead.’

‘So it was Mary’s fault? Is that what you’re saying?’

‘That is what has been suggested to me, but we won’t have the real facts until we’re in there, and you’re managing director. Only then can we start digging.’

‘It won’t be soon enough for me,’ she muttered in a tight voice. Glancing at her watch, she went on, ‘I think I had better go and change. Nicholas Throckman will be arriving here before we know it.’

Elizabeth was in a fury, a fury so monumental she wanted to rush outside and scream it into the wind until she was empty. But she knew it would be unwise to do that. It was an icy morning and there was a bone-chilling wind. Dangerous weather.

And so instead she rushed upstairs to her bedroom, slammed the door behind her, fell down on her knees and pummelled the mattress with her fists, tears of anger glistening in those intense dark eyes. She beat and beat her hands on the bed until she felt the anger easing, dissipating, and then suddenly she began to weep, sobbing as if her heart was breaking. Eventually, finally drained of all emotion, she stood up and went into the adjoining bathroom where she washed her face. Returning to the bedroom she sat down at her dressing table and carefully began to apply her make-up.

How could she do it? How could she tip all the money intoPhilip’s greedy outstretched hands? Out of love and adorationand wanting to keep him by her side? The need to keep himwith her in London? How stupid her sister had been. He wasa womanizer, she knew that only too well. He chased women,he had even chased her, his wife’s little sister.

And the duped and besotted Mary had poured more moneyinto his hands for his real estate schemes in Spain. And withouta second thought, led by something other than her brain. Thaturgent itch between her legs … driving sexual desire … how itblinded a woman.

Well, she knew all about that, didn’t she? The image of thathunk of a man Tom Selmere was still there somewhere in herhead even after ten years. Another man on the make, lusting afterhis new wife’s stepdaughter, and a fifteen-year-old at that. Marriedto Harry’s widow Catherine before Harry was barely cold in hisgrave. And wanting to get Harry’s daughter into his bed as well.Hadn’t the widow woman been enough to satisfy the randy Tom?She had often wondered about that over the years.

Philip Alvarez was cut from the same cloth.

What the hell had Philip done with all that money? Seventy-fivemillion. Oh God, so much money lost … our money … Deravenels’money. He had seemingly never really accounted for it. Would heever? Could he?

We will make him do so. We have to do so. Surely there wasdocumentation? Somewhere. Mary wouldn’t have been thatstupid. Or would she?

My sister’s management of Deravenels has been abysmal. Ihave long known that from my close friends inside the company,and Cecil had his own network, his own spies. He knows a lotmore than he’s telling me; trying to protect me, as always. I trustmy Cecil, I trust him implicitly. He’s devoted, and an honourableman. True Blue. So quiet and unassuming, steady as a rock, andthe most honest man I know. Together we’ll run Deravenels.And we’ll run it into the black.

Rising, Elizabeth left the dressing table, moved towards the door. As she did so her eyes fell on the photograph on the chest. It was a photograph of her and Mary on the terrace here at Ravenscar. She’d forgotten it was there. Picking it up, she gazed at it. Two decades fell away, and she was on that terrace again … five years old, so young, so innocent, so unsuspecting of her treacherous half-sister.

‘Go on, Elizabeth, go to him. Father’s been asking for you,’ Mary said, pushing her forward.

Elizabeth looked up at the twenty-two-year-old, and asked, ‘Are you sure he wants to see me?’