По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

Memory Wall

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Alma felt dizzy. The monster had short, powerful legs, fist-size eyeholes, and a mouth full of fangs. “Says they hunted in packs,” whispered Harold. “Imagine running into six of those in the bush?” In the memory twenty-four-year-old Alma shuddered.

“We think we’re supposed to be here,” he continued, “but it’s all just dumb luck, isn’t it?” He turned to her, about to explain, and as he did shadows rushed in from the edges like ink, flowering over the entire scene, blotting the vaulted ceiling, and the schoolgirl who’d been spitting into the fountain, and finally young Harold himself in his too small khakis. The remote device whined; the cartridge ejected; the memory crumpled in on itself.

Alma blinked and found herself clutching the footboard of her guest bed, out of breath, three miles and five decades away. She unscrewed the headgear. Out the window a thrush sang chee-chweeeoo. Pain swung through the roots of Alma’s teeth. “My god,” she said.

THE ACCOUNTANT

That was three years ago. Now a half dozen doctors in Cape Town are harvesting memories from wealthy people and printing them on cartridges, and occasionally the cartridges are traded on the streets. Old-timers in nursing homes, it’s been reported, are using memory machines like drugs, feeding the same ratty cartridges into their remote machines: wedding night, spring afternoon, bike-ride-along-the-cape. The little plastic squares smooth and shiny from the insistence of old fingers.

Pheko drives Alma home from the clinic with fifteen new cartridges in a paperboard box. She does not want to nap. She does not want the triangles of toast Pheko sets on a tray beside her chair. She wants only to sit in the upstairs bedroom, hunched mute and sagging in her armchair with the headgear of the remote device screwed into the ports in her head and occasional strands of drool leaking out of her mouth. Living less in this world than in some synthesized Technicolor past where forgotten moments come trundling up through cables.

Every half hour or so, Pheko wipes her chin and slips one of the new cartridges into the machine. He enters the code and watches her eyes roll back. There are almost a thousand cartridges pinned to the wall in front of her; hundreds more lie in piles across the carpet.

Around four the accountant’s BMW pulls up to the house. He enters without knocking, calls “Pheko” up the stairs. When Pheko comes down the accountant already has his briefcase open on the kitchen table and is writing something in a file folder. He’s wearing loafers without socks and a peacock-blue sweater that looks abundantly soft. His pen is silver. He says hello without looking up.

Pheko greets him and puts on the coffeepot and stands away from the countertop, hands behind his back. Trying not to bend his neck in a show of sycophancy. The accountant’s pen whispers across the paper. Out the window mauve-colored clouds reef over the Atlantic.

When the coffee is ready Pheko fills a mug and sets it beside the man’s briefcase. He continues to stand. The accountant writes for another minute. His breath whistles through his nose. Finally he looks up and says, “Is she upstairs?”

Pheko nods.

“Right. Look. Pheko. I got a call from that … physician today.” He gives Pheko a pained look and taps his pen against the table. Tap. Tap. Tap. “Three years. And not a lot of progress. Doc says we merely caught it too late. He says maybe we forestalled some of the decay, but now it’s over. The boulder’s too big to put brakes on it now, he said.”

Upstairs Alma is quiet. Pheko looks at his shoetops. In his mind he sees a boulder crashing through trees. He sees his five-year-old son, Temba, at Miss Amanda’s school, ten miles away. What is Temba doing at this instant? Eating, perhaps. Playing soccer. Wearing his eyeglasses.

“Mrs. Konachek requires twenty-four-hour care,” the accountant says. “It’s long overdue. You had to see this coming, Pheko.”

Pheko clears his throat. “I take care of her. I come here seven days a week. Sunup to sundown. Many times I stay later. I cook, clean, do the shopping. She’s no trouble.”

The accountant raises his eyebrows. “She’s plenty of trouble, Pheko, you know that. And you do a fine job. Fine job. But our time’s up. You saw her at the boma last month. Doc says she’ll forget how to eat. She’ll forget how to smile, how to speak, how to go to the toilet. Eventually she’ll probably forget how to swallow. Fucking terrible fate if you ask me. Who deserves that?”

The wind in the palms in the garden makes a sound like rain. There is a creak from upstairs. Pheko fights to keep his hands motionless behind his back. He thinks: If only Mr. Konachek were here. He’d walk in from his study in a dusty canvas shirt, safety goggles pushed up over his forehead, his face looking like it had been boiled. He’d drink straight from the coffeepot and hang his big arm around Pheko’s shoulders and say, “You can’t fire Pheko! Pheko’s been with us for fifteen years! He has a little boy now! Come on now, hey?” Winks all around. Maybe a clap on the accountant’s back.

But the study is dark. Harold Konachek has been dead for more than four years. Mrs. Alma is upstairs, hooked into her machine. The accountant slips his pen into a pocket and buckles the latches on his briefcase.

“I could stay in the house, with my son,” tries Pheko. “We could sleep here.” Even to his own ears, the plea sounds small and hopeless.

The accountant stands and flicks something invisible off the sleeve of his sweater. “The house goes on the market tomorrow,” he says. “I’ll deliver Mrs. Konachek to Suffolk Home next week. No need to pack things up while she’s still here; it’ll only frighten her. You can stay on till next Monday.”

Then he takes his briefcase and leaves. Pheko listens to his car glide away. Alma starts calling from upstairs. The accountant’s coffee mug steams untouched.

TREASURE ISLAND

At sunset Pheko poaches a chicken breast and lays a stack of green beans beside it. Out the window flotillas of rainclouds gather over the Atlantic. Alma stares into her plate as if at some incomprehensible puzzle. Pheko says, “Doctor find some good ones this morning, Mrs. Alma?”

“Good ones?” She blinks. The grandfather clock in the living room ticks. The room flickers with a rich, silvery light. Pheko is a pair of eyeballs, a smell like soap. “Old ones,” Alma says.

He helps her into her nightgown and squirts a cylinder of toothpaste onto her toothbrush. Then her pills. Two white. Two gold. Alma clambers into bed muttering questions.

Wind-borne rain starts a gentle patter on the windows. “Okay, Mrs. Alma,” Pheko says. He pulls the quilt up to her throat. “I got to go home.” His hand is on the lamp. His telephone is vibrating in his pocket.

“Harold,” Alma says. “Read to me.”

“I’m Pheko, Mrs. Alma.”

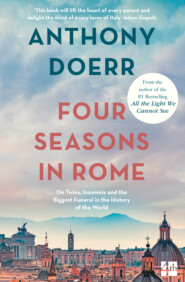

ANTHONY DOERR

Alma shakes her head. “Goddammit.”

“You’ve torn your book all apart, Mrs. Alma.”

“I have? I have not. Someone else did that.”

A breath. A sigh. On the dresser, three lustrous wigs sit atop featureless porcelain heads. “Ten minutes,” Pheko says. Alma lays back, bald, glazed, a withered child. Pheko sits in the bedside chair and takes Treasure Island off the nightstand. Pages fall out when he opens it.

He reads the first paragraphs from memory. I remember him as if it were yesterday, as he came plodding to the inn door, his sea chest following behind him in a hand-barrow; a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man …

One more page and Alma is asleep.

B478A

Pheko catches the 9:20 Golden Arrow to Khayelitsha. He is a little man in black trousers and a red cable-knit sweater. In the bus seat, his shoes barely touch the floor. Gated compounds and walls of bougainvillea and little bistros lit with colored bulbs slide past. At Hanny Street the bus pauses outside Virgin Active Fitness, where three indoor pools smolder with aquamarine light, a last few swimmers toiling through the lanes, an elephantine waterslide disgorging water in the corner.

The bus fills with township girls: office cleaners, waitresses, laundresses, women who go by one name in Cape Town and another in the townships, housekeepers called Sylvia or Alice about to become mothers called Malili or Momtolo.

Drizzle streaks the windows. Voices murmur in Xhosa, Sotho, Tswana. The gaps between streetlights lengthen; soon Pheko can see only the upflung penumbras of billboard spotlights here and there in the dark. Drink Opa. Report Cable Thieves. Wear a Condom.

Khayelitsha is thirty square miles of shanties made of aluminum and cinder blocks and sackcloth and car doors. At the century’s turn it was home to half a million people—now it’s four times bigger. War refugees, water refugees, HIV refugees. Unemployment might be as high as sixty percent. A thousand haphazard light towers stand over the shacks like limbless trees. Women carry babies or plastic bags or vegetables or ten-gallon water jugs along the roadsides. Men wobble past on bicycles. Dogs wander.

Pheko gets off at Site C and hurries along a line of shanties in the rain. Windchimes tinkle. A goat picks its way through puddles. Torpid men perch on fenders of gutted taxis or upended fruit crates or beneath ragged tarps. Someone a few alleys over lights a firework and it blooms and fades over the rooftops.

B478A is a pale green shed with a sandy floor and a light blue door. Three treadless tires hold the roof in place. Bars seal off the two windows. Temba is inside, still awake, animated, whispering, nearly jumping up and down in place. He wears a T-shirt several sizes too large; his little eyeglasses bounce on his nose.

“Paps,” he says, “Paps, you’re twenty-one minutes late! Paps, Boginkosi caught three cats today, can you believe it? Paps, can you make paraffin from plastic bags?”

Pheko sits on the bed and waits for his vision to adjust to the dimness. The walls are papered with faded supermarket circulars. Dish soap for R1.99. Juice two for one. Yesterday’s laundry hangs from the ceiling. A rust-red stove stands propped on bricks in the corner. Two metal-and-plastic folding chairs complete the furniture.

Outside the rain sifts down through the vapor lights and makes a slow, lulling clatter on the roof. Insects creep in, seeking refuge; gnats and millipedes and big, glistening flies. Twin veins of ants flow across the floor and braid into channels under the stove. Moths flutter at the window screens. Pheko hears the accountant’s voice in his ear: You had to see this coming. He sees his silver pen flashing in the light of Alma’s kitchen.

“Did you eat, Temba?”

“I don’t remember.”

“You don’t remember?”

“No, I ate! I ate! Miss Amanda had samp and beans.”

“And did you wear your glasses today?”