По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

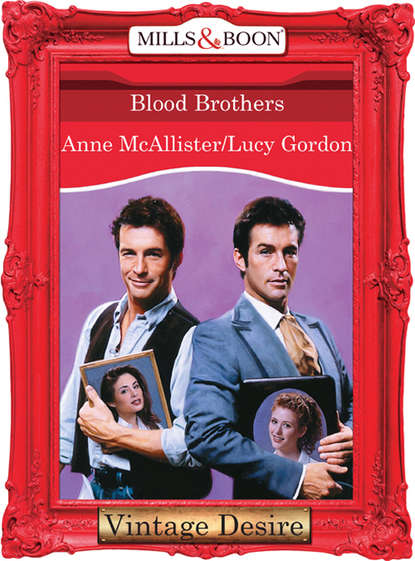

Blood Brothers

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You don’t think I can do it?”

“It’s work,” Earl pointed out.

“You don’t think it’s work to raise cattle? You don’t think it’s work to sort and ship and doctor a herd?”

“Your father worked hard,” Earl allowed.

Big of him! Gabe gritted his teeth. “I worked with him!”

“You lent a hand when you passed by.”

“Who do you think did it since Dad died last year?”

“You?” Earl almost seemed to chuckle. “I thought that’s why your mother hired Frank as foreman. Or maybe Martha did it or that little orphan girl, Claire. Your mother says she lives in jeans and does the work of three men. Who needs you?”

Gabe’s teeth came together with a snap. “Think again.”

“You don’t say you’re actually good for a job of work, surely?” Earl regarded him with tolerant amusement.

“I’m good for anything he’s good for,” Gabe snapped, indicating Randall.

“Ho, ho, ho!” Earl scoffed.

“Don’t ho-ho me, old man—”

“And don’t call me old man—”

“Look—” Randall ventured.

As one, the other two turned on him. “YOU KEEP OUT OF IT!”

“Whatever needs to be done, I’ll do it,” Gabe said defiantly. “And you—” to Randall “—give me the details of this paper, and go take a vacation. Or ‘a holiday,’ I suppose you’d call it.”

“What I’d call it is madness.” Randall shook his head fiercely. “You’ll bankrupt us.”

Gabe slammed his glass down on the table. “Sez who? You think I can’t run things? I’ll show you. I’m off to Devon in the morning!”

There was silence.

Randall and Earl looked at each other. Then at Gabe.

Gabe glared back at them. And then, just as the adrenaline rush carried him through an eight-second bull ride mindless of aches, pains and common sense, before it drained away, so did the red mist of fury disperse and the cold clear light of reality set in.

And he thought, oh hell, what have I done?

Slowly, unconsciously, he raised a hand and ran his finger around the inside of the collar of his own shirt.

Much later the cousins put Earl to bed, then supported each other as far as Gabe’s room, where he produced a bottle of Jack Daniel’s.

“Seriously,” Randall said, “it’s a crazy idea…”

“Yep, it is.” Gabe poured them each a glass and lifted his. “To the Buckworthy Gazette!”

“You don’t have to do—”

“Yes,” Gabe said flatly. “I do.” He downed the whisky in one gulp, then set the glass down with a thump and threw himself down onto his bed to lie there and stare up at his cousin. Randall looked a little fuzzy.

Gabe felt a little fuzzy, but determined. “Seriously,” he echoed his cousin. “Remember when we were kids and you came to Montana for the first time. We became blood brothers, swearing to defend and protect each other against all comers. Well, that’s exactly what I’m doing.”

Randall shook his head. “I don’t need protecting!”

Gabe wasn’t convinced, but he wasn’t going to argue. He shoved himself up against the headboard of the bed and reached for the bottle again. Carefully he poured himself another glass, aware of Randall’s tight jaw, his cousin’s years of hard work and legendary determination.

“There’s another thing, too. You’re not the only Stanton,” he muttered.

Randall blinked. “What?”

Gabe looked up and met his cousin’s gaze. “I can do this.” Though, as he said the words, Gabe wondered if he was saying them for Randall’s ears or for his own. “It will be fun,” he added after a moment with a return of his customary bravado.

“But you don’t know what you’re getting into.”

Gabe held up his glass and watched the amber liquid wink in the light.

“That,” he said, “is exactly why it’s going to be fun.”

One

How hard could it be?

Gabe was determined to look on the positive side. There was no point, after all, in bemoaning his impulsive decision. He’d said he would do it, and so he would. No big deal.

Randall apparently did this sort of thing all the time—dashed in on his white horse—no, make that, sped in in his silver Rolls-Royce—and rescued provincial newspapers from oblivion, set them on their feet, beefed up their advertising revenues, sparked up their editorial content, improved their economic base and sped away again—just like that.

Well, fine. Gabe would, too. No problem. No problem at all.

The problem was finding the damn place!

Gabe scowled now as he drove Earl’s old Range Rover through the gray morning drizzle that had accompanied him from London, along the narrow winding lane banked by dripping hedgerows taller than his head.

He’d visited the ancestral pile before, of course, but he’d never driven himself. And he’d always come in the middle of summer, not in what was surely the dampest, gloomiest winter in English history.

He’d left way before dawn this morning, goaded by Earl having said something about Randall always getting “an early start.” He’d done fine on the motorway, despite still having momentary twitches when, if his concentration lapsed, he thought he was driving on the wrong side of the road.

It had almost been easier when he’d got down into the back country of Devon and the roads had ceased having sides and had become narrow one-lane roads. His only traumas then came when he met a car coming in the other direction and he had to decide which way to move. Finally though, he found a sign saying BUCKWORTHY 3 mi and below it STANTON ABBEY 2 mi.

He turned onto that lane, followed it—and ended up on a winding track no wider than the Range Rover.

He felt like a steer on its way to the slaughterhouse—funneled into a chute with no way out.