По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

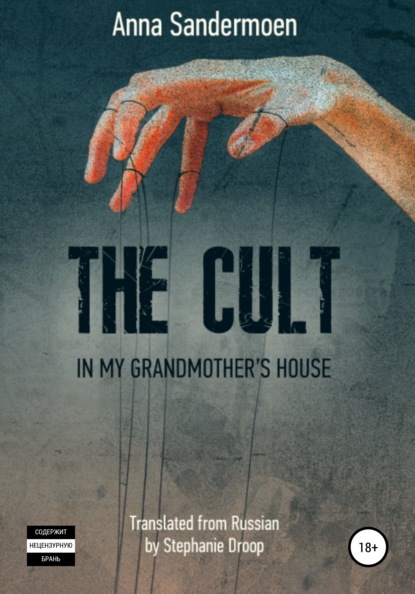

The Cult in my Grandmother's House

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

However, to outsiders it must have seemed that we were all absolutely fine, never ill, that nothing ever happened to us and that we were always full of strength, despite our heavy labour and difficult circumstances. In fact, this was the whole point and message of our work: don’t spoil children, don’t raise them as little lords, let them work their arses off, suffer the slings and arrows, temper them in the fire!

But to an intelligent observer it was obvious that we fell sick no less frequently than other people, and maybe even more. It was just that the whole theme of illness was painstakingly hushed up around us. Whenever anyone fell ill they were rapidly quarantined, so rapidly that not even others in the cult noticed. If for some reason they couldn’t be quarantined, they were scolded for their wrong thoughts, bad attitude and behaviour.

People even died like this. As a child I was always surprised that the fact of a person’s death was so quickly glossed over. There was never any public mourning or grief, never anything special or solemn – nothing that should by rights conclude the life of a worthy person, or so it seemed to me. Somehow no one was up to it.

However, when Brezhnev died, we were obliged to grieve. But the death of the Chief’s youngest daughter’s newborn baby was put down to the cold weather. Not to the fact that his mother had wrong thoughts, or that she was a perverted woman, or that she had done something wrong to the baby, but to the fact that there was frost outside: the baby had quite simply and routinely frozen in his pram during a nap. It was the frost that was guilty. The chosen ones are excused everything.

When I was first writing my recollections (at age 23), I declared completely sincerely that, yes, seriously, despite everything, we were never ill. I really believed that. But now, with the years, remembering our life then in more detail, and through talking with other former cult members, I uncovered facts which as a child I had never even known. In fact, as often happens, much was hidden from the children intentionally.

I came to see that it is important to fact-check our childhood impressions.

WHO REMEMBERS THEIR CHILDHOOD IN THE USSR

Here in Switzerland, I know a Russian lady who is surprised every time I mention the USSR with ill will. “But what was so bad about it?” she says, “Soviet people had everything. Even if it wasn’t much, everyone had a roof over their head, free education and medicine, a job, a salary. Everything stable and predictable. Is that not heaven?!”

True, it came out later that in the USSR she had lived in her parents’ apartment, and her dad was in the army, so they were in a very privileged layer of society and had more or less enough. (They were the total opposite of our family, which was headed by an enemy of the people). That aside, her recollections of the Soviet Union are tainted with childish romanticism. Children do not see the complex relationships in social phenomena. We begin to notice and understand them only with years and experience.

This is why it is so important in adulthood to mentally return to our childhood, to reevaluate what happened then. This is why I am writing this book: I want to understand what was not right and how to make sure nothing similar happens again, either with my own children or other people’s.

THEATRE, OR ART THERAPY

There was never enough living space, and still more and more people kept joining the collective. We had to find somewhere to set up and conduct our activities. No one lived in the clinic in the centre of Dushanbe – that was where the adults worked. We lived in various apartments donated by the parents of children in the commune. My grandmother’s apartment was the headquarters, where the management lived.

Besides the speeches, layering and mechanotherapy, we also received other methods of treatment, such as art therapy: the commune had its own amateur drama group. The Chief said that theatre was a powerful psychological corrective agent. By acting on a stage, a person becomes liberated, loses their fear of appearing in public, and learns how to be sincere.

We were invited to appear on stages in the local halls where we rehearsed, and then we went on tour over the whole country. During my early days in the collective we put on Edmond Rostand’s “Cyrano de Bergerac”. By that time we already had lots of people. They came from over the whole Soviet Union: from Moscow, Leningrad, Dmitrov, the Urals, Siberia, and of course many were from Dushanbe.

I really liked the theatre. It was interesting. Sometimes we rehearsed for days on end and simply lived on the stage and in the wings. And we received our treatments too: we were tapped and layered right there on the floor in the wings.

We had a large repertoire: we could perform about 20 different plays.

One time in the assembly hall of one school we were putting on “Dunno in the Sun City”, a story about the loveable children’s character Dunno or Neznaika created by Nikolai Nosov. I was playing Mushka. In the hall sat my parents, who had arrived for a short visit. The Chief was also watching our play. In the flow of a rehearsal he stopped us. He often did that, to start his latest speech, discussing the behaviour of this person or that person.

On this occasion the Chief was disgruntled with me. He spun a long speech, whose point I can’t remember. Then he told my parents to have a word with me. Mum and dad led me into an empty classroom, gave me a long explanation, of which I remember absolutely nothing, then sat me on a chair. Mum twisted my arms behind the chair’s back and held them so I couldn’t free myself, while my dad repeatedly beat me in the face. My nose started bleeding heavily, and my dad just kept hitting me. Later I returned home to the commune without my parents, took off my favourite dress and soaked it in a bath of cold water, but still couldn’t get the blood out. I had to throw it away.

Years later I asked my dad how he could have done such a thing to me. My dad swore he couldn’t remember anything of the sort. I believe him, now. Now I know that sometimes people simply wipe the most hideous things from their memory, because it is just as unbearable to remember as to explain.

~

“How many points would you rate your anger?”

“9”

“And protest?”

“9”

“Very good. Now let’s layer you, to remove the aggression.”

A SLAP IN THE FACE IN CHEBOKSARY

Once in Cheboksary we were appearing on stage at a boarding school. We were putting on “Terem-Teremok”, a popular cartoon of a folk tale. For the whole of my time in the collective I played the frog in that play. On this occasion I had just finished the first scene, and the curtain closed. The Chief flew up to me unexpectedly and slapped me in the face with a wide-flung arm, shouting in my face, “Will you just act normally today, you bastard?! Relax right now and stop getting angry, you beast!” I could hardly come to before the curtain had already opened. With a full hall in front of me I had to continue the play. My cheek was burning like it had been scalded. I quickly took myself in hand and acted the play to the end.

It seemed to me at the time – and for many years afterwards I was convinced! – that thanks to that slap in the face I got a wonderful sensation of release and absolute relaxation. It seemed that I started to feel, that my body started suddenly moving freely, my rhythm of motion loosened up, it became easy to speak, my fear of performing fell away, and I finished the play with aplomb. I think the Chief must have instructed my parents to do the same when they beat me after pulling me out of the play about Dunno.

What conclusion could I draw from this? Not to slack off. That every time you have to give everything, as if it’s the last time. And be prepared for the fact that it really could be the last time. Every time.

I was rarely given the roles I wanted to play. Most often I was just an extra. That was boring, especially when you take into account that we performed the same shows for many years. I was already totally sick of the monotony, and even in small roles I tried with all my might to show I was capable of more, so that someone would finally notice me and let me act something more significant. But to my disappointment, no one trusted me with the large or interesting roles. They were given to the chosen ones. For example, the role of the little bandit in “The Snow Queen”, which I fantasised about, went to the daughter of a party apparatchik. She was praised in every possible way, her talent was publicly lauded. I envied her terribly but I already understood: I would never see that role, for the simple reason that she needed it more than me. See, she was the daughter of a high-ranking official and was therefore “sicker” than me. This meant she needed treatment more than I did.

The biggest roles were given to the sickest (and therefore most talented) kids. The Chief explained it like this: schizophrenia conceals a person’s true talents, which are revealed thanks to the treatment. But the logic was still not clear to me: if I was not given any significant roles, then it followed I couldn’t really be that sick. So why were they constantly scolding me and trying to cure me? Did that mean it was a good thing to be schizophrenic? Did it mean you had talent? So if I wasn’t schizophrenic, then I must just be mediocre. Or so I reasoned as a child.

In the meantime we were performing on big stages all over the country; we were even invited to a television studio and then shown on television. This was an absolutely huge event! See, in those times, Soviet television had only three channels, and to get on it was practically impossible.

So even though I was only an extra, I was still part of something bigger than myself, and at least there were people sicker than I was. That meant I was already on the right path.

But since then, before any public appearance I am gripped by an animal fear. I need to expend huge effort to deal with it.

~

“How many points is your anger at?”

“At 9”

“And your protest?”

“At 7”

“Very good. Now let’s layer you, to get rid of the aggression. You’ll calm down, and you won’t protest any more. Lie down and get ready for the procedure.”

THE CORE AND THE FILTH

The people in the collective were constantly changing. Someone would be driven out for bad behaviour and someone else would join. Our number ranged from about 30 to 200. But there was a core of constant members, and it was a great honour to be in that core.

We lived in communes in strict hierarchy: each group had a head teacher and assistant teacher, and the children also had a chairperson and a board of leaders (leaders were reelected periodically). Everyone else was “filth”, that is, those who were being treated. That’s exactly what they called us — filth. I was among the filth.

The filth often had to undergo psychotherapy (also known as mechanotherapy or often simply facebeating). Children were also beaten on the backside with a belt. Not everyone was beaten, only those whose parents wouldn’t cause trouble, that is, who were the most blinded by the collective’s ideology. Of course I was among this group of children.

Up to 20 people would live in a two- to three-room apartment. We slept on the floor under communal blankets with communal pillows, without any bedlinen. Everyone took turns to cook. Our rations were very meagre, usually just porridge and packet soup.

It was considered that the poorer the living conditions and food, the stronger would be the spirit.

MY SECOND YEAR OF SCHOOL

When the first school year started in Dushanbe, all the children from the commune went to one school in the centre of town. I was in the second year, in the second class. There were several of us in this class, and we all lived together for a time. There were three teachers in charge of us who read us books and made sure we did our lessons.

By this time we were all so well trained that we would spy on each other, children on children. We thought we were doing the right thing, that we had to help each other so we didn’t fall prey to schizophrenia.

One time a girl from the commune ate a whole apple at breaktime and didn’t share it with anyone. One of our group noticed and quickly ran round telling everyone. We decided to meet after class and have words with that girl. We met, gave speeches, and then hit her in the face, like the adults did with us. She couldn’t even fight us because then she would have got even worse from the teachers. We weren’t even doing it out of envy for her apple, but because we didn’t want to see her ruined by schizophrenia and whoredom.