По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

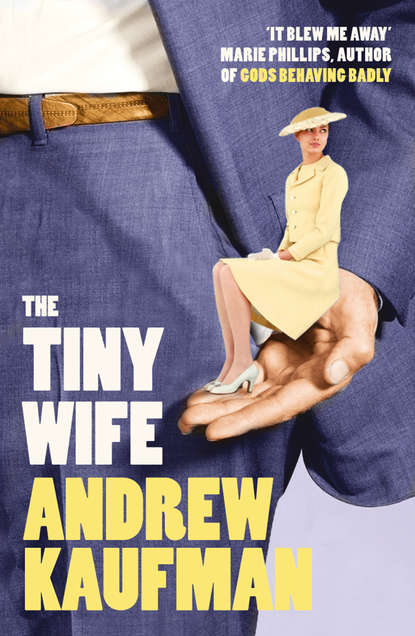

The Tiny Wife

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

hree days after the robbery, and merely minutes after we’d finally gotten Jasper to sleep, our phone rang. It was our home line, which we usually let go to voicemail, but Stacey raced to answer it. Later she would explain that it had sounded urgent – an alarm, not just a ring.

The caller was Detective William Phillips, who had stood ninth in line and had given the robber a large antique key. Detective Phillips asked if anything peculiar was happening in her life, anything new and, perhaps, inexplicable. She asked him to elaborate. The detective told her that in the last twenty-four hours he had received confessions from two different husbands, claiming to have murdered their wives. He went on to explain that both of these cases involved someone who’d been inside Branch #117 at the time of its robbery.

Stacey asked for still more detail. Detective Phillips related the following stories.

Two mornings after the robbery, Daniel James, who had stood fifth in line and had given the thief a photograph of his wife’s parents’ wedding was tying his shoes when the lace in his right shoe broke. He put on his other pair of dark shoes and the lace in the left shoe broke. He changed into his light suit but, when tightening the lace on his right brown shoe, it, too, broke. He looked at the lace in his hand. He looked at the laces on the floor. ‘I have to leave you,’ he said to his wife, but she was already gone.

That same day Jenna Jacob woke to discover that she was made of candy, an event she remained unaware of until she was in the shower and looked down and saw a white film swirling to the drain.

Shocked and disbelieving, Jenna turned off the tap and wiped the steam from the mirror. Her skin was made of white sugar with mint speckles. Her hair was licorice. Her eyes were caramels. The longer she stared at her reflection, the less strange this candied version of herself became. She wrapped a scarf around her licorice hair, put sunglasses over her caramel eyes, and went downstairs. Her sons, aged ten and thirteen, barely noticed.

When her kids wouldn’t eat their breakfast, she rubbed her hands together over their cereal bowls, dusting their Shreddies with sugar. When they wouldn’t get dressed and into the car, she broke off her pinkie fingers and used them as bribes. When she dropped them off at school, they were unusually eager to kiss her goodbye.

Jenna returned home, called in sick, and spent the day watching television. Just after nine, her husband came home.

‘Sorry I’m so late,’ he said. ‘It’s the Meyer’s account again. Why’s it so dark in here? Is there anything to eat?’

Jenna patted the cushion beside her. Her husband sat down. He kissed her candied lips. He kissed her neck and her arms and her face. They went upstairs. He kissed every part of her body.

‘I could eat you up,’ he said, and, lost in passion, he did.

‘Are you joking with me?’ I heard my wife ask.

‘Unfortunately, I’m not. I’ve found several other cases. One in Halifax, three in the southern United States, also in Lille, France, Barcelona, and Winnipeg. It’s the same m.o. – purple hat, emotionally significant object, the whole thing. You are in danger.’

‘Am I?’

‘There will be a meeting of all the survivors, everyone who was inside Branch #117, this Monday at 7.15 at St Matthew’s United Church. I can’t stress enough how important it is that you attend.’

‘Well, thank you for your call,’ my wife said. She hung up, but her hand remained on the phone.

Chapter 4

hat night I was in the bathroom brushing my teeth when Stacey called for me, and her voice held such urgency that I carried my toothbrush into the bedroom. She stood in front of the mirror, staring at the neckline of the T-shirt she most often wore to bed. She pointed out how baggy it was, which I hadn’t noticed – the neckline plunged, and now cleavage was showing.

‘Nothing wrong with that,’ I said. I held her from behind. I tried to kiss her neck. She twisted away from me.

‘I’m shrinking.’

‘You’re not shrinking.’

‘You need to listen to me.’

‘Couldn’t it just be the laundry?’

‘Even inside, I can feel it. I’m shrinking.’

‘That guy’s just put this into your head and you’ve run with it. You know how you’re prone to run with things.’

‘For once can you not question everything I say?’ Stacey asked.

I sat down on the bed. There was a tape measure on the bedside table, unmoved from some renovations we’d been contemplating. I picked it up with my free hand.

‘Why don’t we measure you?’

‘I don’t know how tall I was before.’

‘It’ll be on your driver’s license.’

‘Right,’ Stacey said. She ran downstairs and returned with her driver’s license and a pencil. I put my toothbrush down where the tape measure had been sitting. Making sure her knees were straight against the doorframe, I patted her hair down and stroked a black line on the white paint of the wall. We opened the tape measure.

‘One hundred and fifty-nine centimeters.’ ‘Oh my God.’

Stacey handed me her license. Her height was listed as one hundred and sixty centimeters.

‘They could have made a mistake,’ I said. ‘Or maybe we should measure again?’

I stood by the door. I measured again. Her exact height was one hundred and fifty-nine centimeters and one millimeter. I read the license again. It still said that she should be one hundred and sixty centimeters tall. Stacey continued to sit on the bed, staring at the wall.

Chapter 5

n the morning we measured her again. She put her heels against the door jamb and straightened her posture. I pushed down her hair and made sure the pencil was flat. A second black line was made on the white paint. She stepped forward and I measured.

I decided to be as precise as I could be. I measured to the millimeter. What I found was not good. Yesterday she stood 1,591 millimeters tall; now she was 1,581 millimeters, a loss of 10 millimeters overnight and 19 millimeters in total.

We sat on the edge of the bed. Her feet didn’t touch the floor. I couldn’t remember if they ever had. I turned the tape measure in my hand. Stacey watched the floor and I watched her.

The rest of the day was spent measuring things. Stacey and I became obsessed with it. We measured the length of our bed, and the distance between the bedspread and the floor, and how far apart the curtains were when open. We measured our incisor teeth and the circumferences of our necks. We went outside and calculated the combined length of the cracks in the sidewalk in front of our house, and the average amount left unsmoked on discarded cigarette butts. We measured all that. We measured the next day too, and then we picked up Jasper from daycare and drove straight to St Matthew’s United Church. I parked across the street. Jasper started crying.

‘I guess I’d better go,’ Stacey said. I measured the concern in her voice and agreed.

Stacey leaned between the seats and kissed Jasper. This made him stop crying momentarily, but he started again when she got out. She shuffled over the curb and up the stairs of the church. The arms of her sweater and the cuffs of her pants were turned up several times. She looked back twice, both times at Jasper.

The account of what followed is what Stacey told me happened. I have no reason to doubt that she told me anything but the truth, but I admit that I did not witness any of these events. Stacey told me that her initial impression was that the basement of St Matthew’s United Church had been chosen because the dingy linoleum floor, low ceiling, and florescent lighting made it the perfect place for a support group to meet. Folding chairs had been unfolded and placed in a circle. A stack of upturned Styrofoam cups sat beside a giant silver pot of drip-brewed coffee. The only thing missing was everybody else: Stacey had arrived exactly on time, but even Detective Phillips was nowhere to be seen.

Stacey filled a white Styrofoam cup and stirred in sugar with a brown plastic stick. To the right of the coffee pot were a fan of name tags and several Sharpie magic markers. Stacey uncapped a marker, but as the tip touched the paper she paused. An inkblot formed on the top left corner of the name tag. When she started writing again, she did not write Stacey; she wrote Calculator. As she placed the sticker on her chest, she heard someone coming down the stairs.

The steps were heavy and quick and belonged to a woman. When she reached the bottom of the stairs she did not stop to introduce herself. She took the folding chair from the top of the circle and dragged it across the floor to the west wall, where a small window near the top looked onto the street. She stood on the chair and stared out the window. Several other sets of footsteps went by, and then she breathed. She jumped off the chair and joined Stacey by the coffee.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: