По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

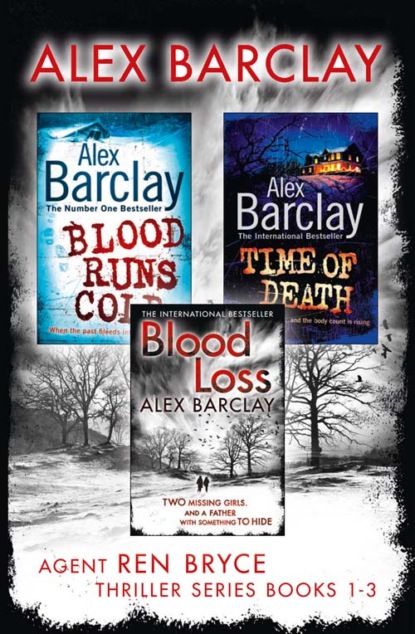

Agent Ren Bryce Thriller Series Books 1-3: Blood Runs Cold, Time of Death, Blood Loss

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Try this for mean: “Vincent, you’re dull is your problem. You’re conservative and stifling. You want me to be someone else. You can’t accept who I am. You stand there, you righteous prick, and try and tell me what to do? Fuck you, Vince. Fuck you, because you have no idea how to live. None. You court the sameness of life because it is safe. And you like safe.” All this, Ren, because I refused to buy the drunken lady here another vodka.’

Ren paused. ‘Well, it’s not like you are the most spontaneous guy in the world.’

‘Oh my God,’ said Vincent. ‘See? This is what I mean! This is why I believe you! Because in all sobriety, however many hours later, even you find the truth in what you were saying. At the same time as trying to claim you were drunk and senseless.’

‘I was senseless.’

‘What, but now you see the merit in your ramblings? Oh God, how many times have I had this conversation with you? It is so fucking painful.’ He stabbed a finger her way. ‘This is dull, Ren. This. You accuse me of being dull –’

‘Get some perspective –’

‘Me? Me? Jesus Christ. That’s it. I’ve had it. I cannot do this any more. I can’t. I give up.’

‘What do you mean, you give up?’

‘Exactly that. I’m out of here. I’ve had too much of Ren Noir.’

She tried to smile. ‘You like Ren Noir. She keeps things interesting.’

‘Right now? I think she’s a bitch.’

Tears welled in Ren’s eyes.

‘And,’ said Vincent, ‘I’m all out of sympathy.’ He walked up to her and kissed her on the head. ‘Look after yourself. I won’t be here when you get home.’

Ren stared at his back as he walked away through the living room. Fuck him.

Her hand shook as she picked up her purse and pulled out her FBI creds. She snapped them on to the right inside breast pocket of her jacket and walked out the door.

Chapter 2 (#u8bb60e53-87b4-54e1-a600-62c12d8c99b9)

Breckenridge, Colorado

Downstairs at Eric’s was dark, packed and loud. The hallway was filled with kids in snow boots and giant parkas pounding pinball machines. By the entrance to the restaurant, two groups of schoolgirls stood hanging from each others’ shoulders, waiting for a table. Half of them were Abercrombied, the other half Fitched. Inside, skinny blondes too old for braids leaned against the wall by the kitchen, flashing the restaurant logo on the backs of their T-shirts: Downstairs at Eric’s: Because Everywhere Else Just Sucks.

Sheriff Bob Gage sat with a beer in one hand and a clean fork in the other.

‘Damn, where is my pizza?’

‘On a little yellow piece of paper,’ said Mike Delaney.

‘Hours from registering on my weighing scales.’

Mike rolled his eyes. ‘Can forty-six-year-old men be body dysmorphic?’

‘If I knew what that was, I’d love to tell you,’ said Bob.

‘You know – when you see yourself different to how everyone else sees you. Like you, for example, think you’re fatter than you actually are.’

‘Really? Are you kidding me?’

‘No,’ said Mike. ‘You’re a reasonably tall guy, Bob. You can carry a few extra pounds.’

Bob gave him a side-glance. Mike used to be a tanned, blond ski bum. Now, at thirty-eight, he was a tanned, blond, ski-bum Undersheriff, his eyes always a little red, his skin a little burnt, his lips pale from sunblock. Bob had choirboy styling – polished skin, neat side-parted brown hair, conservative clothes – but it couldn’t quite hide the crazy. Most women were attracted to both of them, for different reasons.

The first night they worked together, they’d gone on a domestic violence call-out and the woman had told them she’d like to be ‘wined and dined with you, Sheriff, so’s you could laugh me right into bed with your pal, blondie, here.’ Bob had looked at her and said, ‘Didn’t Blondie sing “I’m gonna getcha”? Yeah, well, gotcha! And probably gotcha for another twenty years for beating the shit out of that poor husband of yours.’ She had looked at him and said, ‘I would never lay a finger on you, cutie. Can you smell my breath? It’s Wintergreen. Winter in my mouth, but summer in my heart.’

Bob had shot a glance at Mike. ‘What you have is Seasonal Affective Disorder,’ he said, struggling to cuff her.

She made a grab for Mike’s crotch, but he blocked it at the last minute.

‘Yes,’ Bob said, ‘you’re clearly very SAD.’

A waitress walked toward them, raising, then lowering Bob’s hopes.

‘I have not eaten since breakfast,’ he said to Mike. ‘I shouldn’t feel bad about this.’ He raised his cellphone, showing Mike a screen that told him Bob had fifteen missed calls or messages. ‘Do you see this shit?’ said Bob. ‘Half an hour I want – of peace – after everything. Just thirty minutes.’

The Summit County Sheriff’s Office shared a building with the jail and the courthouse. A riot had stolen his previous three hours.

‘You need to keep some beef jerky in your drawer, some trail mix, anything,’ said Mike.

‘Gross,’ said Bob.

Mike started to speak, but both their phones began to vibrate. The calls were from Dispatch.

‘Look, let me take mine at least,’ said Mike. ‘Something is going on.’ He pressed the Answer key and held the phone to his ear.

‘Mike Delaney,’ he said, then paused. Bob could hear a woman’s voice talking quickly at the other end. Mike gestured to a waitress for her notepad. He scribbled across the page, nodding as he wrote. ‘OK,’ he said finally. ‘Me and Bob will be along right away.’ He hung up.

‘No, no, no,’ said Bob. ‘Bob doesn’t like “along”.’

‘Ooh,’ said Mike, ‘Bob is about to go up a mountain on the coldest January day Breckenridge has seen in about fifty years.’

‘Oh, dear God, no,’ said Bob, checking his watch. ‘It’s three fifteen. I’m almost home and dry. Why?’

‘Search and Rescue got an anonymous tip-off. It all sounded a little bullshitty to them, but they checked it out and, sure enough, they found a body.’

‘What?’

Mike nodded.

‘Holy shit,’ said Bob, his eyes wide. Mike turned around to where Bob was staring.

‘It’s my pizza!’ Bob grabbed the waitress’s arm. ‘In a box, sweetheart. And I love you right now. You have no idea.’

Quandary Peak could breathe with the breath it stole from your lungs. Stony and chiseled, it could turn on you before you had the chance to conquer it. The sky overhead showered unpredictable snow and rain, beamed surprise sun. Two-hundred-year-old miners’ cabins hid in the lodgepole pines that marked the timberline before the peak grew bare and rocky up to its full 14,265 feet.

On its south side, Blue Lakes Road stretched two and a half miles off Highway 9 to meet it. In winter, it was plowed halfway. A small group of Search and Rescue volunteers stood by the trailhead sign, like a spread from a North Face commercial. Others sat in their 4x4s, gunning their heating against the outside minus sixteen. They all had different day jobs, but came together every Wednesday night to train for Search and Rescue. They were twenty-two to sixty-two, high-energy, wired and bold.