По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

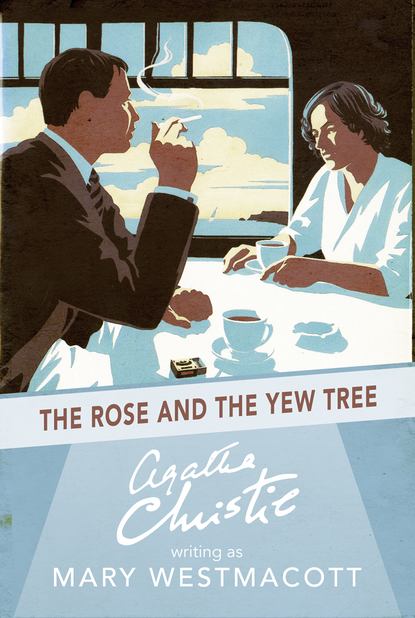

The Rose and the Yew Tree

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Robert and Teresa were perfectly willing for the Carslakes to continue as tenants. Indeed, it was doubtful if they could have turned them out. But it meant that a great deal of pre-election activity centred in and around Polnorth House as well as the Conservative offices in St Loo High Street.

Teresa, as she had foreseen, was swept into the vortex. She drove cars, and distributed leaflets, and did a little tentative canvassing. St Loo’s recent political history was unsettled. As a fashionable seaside watering place, superimposed on a fishing port, and with agricultural surroundings, it had naturally always returned a Conservative. The outlying agricultural districts were Conservative to a man. But the character of St Loo had changed in the last fifteen years. It had become a tourist resort in summer with small boarding houses. It had a large colony of artists’ bungalows, like a rash, spread along the cliffs. The people who made up the present population were serious, artistic; cultured and, in politics, definitely pink if not red.

There had been a by-election in 1943 on the retirement of Sir George Borrodaile at the age of sixty-nine after his second stroke. And to the horror of the old inhabitants, for the first time in history, a Labour MP was returned.

‘Mind you,’ said Captain Carslake, swaying to and fro on his heels as he imparted past history to Teresa and myself, ‘I’m not saying we didn’t ask for it.’

Carslake was a lean, little dark man, horsy-looking, with sharp, almost furtive eyes. He had become a captain in 1918 when he had entered the Army Service Corps. He was competent politically and knew his job.

You must understand that I myself am a tyro in politics—I never really understand the jargon. My account of the St Loo election is probably wildly inaccurate. It bears the same relation to reality as Robert’s pictures of trees do to the particular trees he happens to be painting at the moment. The actual trees are trees, entities with barks and branches and leaves and acorns or chestnuts. Robert’s trees are blodges and splodges of thick oil paint applied in a certain pattern and wildly surprising colours to a certain area of canvas. The two things are not at all alike. In my own opinion, Robert’s trees are not even recognizable as trees—they might just as easily be plates of spinach or a gas works. But they are Robert’s idea of trees. And my account of politics in St Loo is my impression of a political election. It is probably not recognizable as such to a politician. I daresay I shall get the terms and the procedure wrong. But to me the election was only the unimportant and confusing background for a life-size figure—John Gabriel.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_d1ed34db-35e2-5f0a-bb8a-cee1139e56e1)

The first mention of John Gabriel came on the evening when Carslake was explaining to Teresa that as regards the result of the by-election they had asked for it.

Sir James Bradwell of Torington Park had been the Conservative candidate. He was a resident of the district, he had some money, and was a good dyed-in-the-wool Tory with sound principles. He was a man of upright character. He was also sixty-two, devoid of intellectual fire, or of quick reactions—had no gift of public speaking and was quite helpless if heckled.

‘Pitiful on a platform,’ said Carslake. ‘Quite pitiful. Er and ah and erhem—just couldn’t get on with it. We wrote his speeches, of course, and we had a good speaker down always for the important meetings. It would have been all right ten years ago. Good honest chap, local, straight as a die, and a gentleman. But nowadays—they want more than that!’

‘They want brains?’ I suggested.

Carslake didn’t seem to think much of brains.

‘They want a downy sort of chap—slick—knows the answers, can get a quick laugh. And, of course, they want someone who’ll promise the earth. An old-fashioned chap like Bradwell is too conscientious to do that sort of thing. He won’t say that everyone will have houses, and the war will end tomorrow, and every woman’s going to have central heating and a washing machine.

‘And, of course,’ he went on, ‘the swing of the pendulum had begun. We’ve been in too long. Anything for a change. The other chap, Wilbraham, was a competent fellow, earnest, been a schoolmaster, invalided out of the Army, big talk about what was going to be done for the returning ex-serviceman—and the usual hot air about Nationalization and the Health Schemes. What I mean is, he put over his stuff well. Got in with a majority of over two thousand. First time such a thing’s ever happened in St Loo. Shook us all up, I can tell you. We’ve got to do better this time. We’ve got to get Wilbraham out.’

‘Is he popular?’

‘So so. Doesn’t spend much money in the place, but he’s conscientious and got a nice manner with him. It won’t be too easy getting him out. We’ve got to pull our socks up all over the country.’

‘You don’t think Labour will get in?’

We were incredulous about such a possibility before the election of 1945.

Carslake said of course Labour wouldn’t get in—the county was solidly behind Churchill.

‘But we shan’t have the same majority in the country. Depends, of course, how the Liberal vote goes. Between you and me, Mrs Norreys, I shan’t be surprised if we see a big increase in the Liberal vote.’

I glanced sideways at Teresa. She was trying to assume the face of one politically intent.

‘I’m sure you’ll be a great help to us,’ said Carslake heartily to her.

Teresa murmured, ‘I’m afraid I’m not a very keen politician.’

Carslake said breezily, ‘We must all work hard.’

He looked at me in a calculating manner. I at once offered to address envelopes.

‘I still have the use of my arms,’ I said.

He looked embarrassed at once and began to rock on his heels again.

‘Splendid,’ he said. ‘Splendid. Where did you get yours? North Africa?’

I said I had got it in the Harrow Road. That finished him. His embarrassment was so acute as to be catching.

Clutching at a straw, he turned to Teresa.

‘Your husband,’ he said, ‘he’ll help us too?’

Teresa shook her head.

‘I’m afraid,’ she said, ‘he’s a Communist.’

If she had said Robert had been a black mamba she couldn’t have upset Carslake more. He positively shuddered.

‘You see,’ explained Teresa, ‘he’s an artist.’

Carslake brightened a little at that. Artists, writers, that sort of thing …

‘I see,’ he said broad-mindedly. ‘Yes, I see.’

‘And that gets Robert out of it,’ Teresa said to me afterwards.

I told her that she was an unscrupulous woman.

When Robert came in, Teresa informed him of his political faith.

‘But I’ve never been a member of the Communist Party,’ he protested. ‘I mean, I do like their ideas. I think the whole ideology is right.’

‘Exactly,’ said Teresa. ‘That’s what I told Carslake. And from time to time we’ll leave Karl Marx open across the arm of your chair—and then you’ll be quite safe from being asked to do anything.’

‘That’s all very well, Teresa,’ said Robert doubtfully. ‘Suppose the other side get at me?’

Teresa reassured him.

‘They won’t. As far as I can see, the Labour Party is far more frightened of the Communists than the Tories are.’

‘I wonder,’ I said, ‘what our candidate’s like?’

For Carslake had been just a little evasive on the subject.

Teresa had asked him if Sir James was going to contest the seat again and Carslake had shaken his head.

‘No, not this time. We’ve got to make a big fight. I don’t know how it will go, I’m sure.’ He looked very harassed. ‘He’s not a local man.’

‘Who is he?’