По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

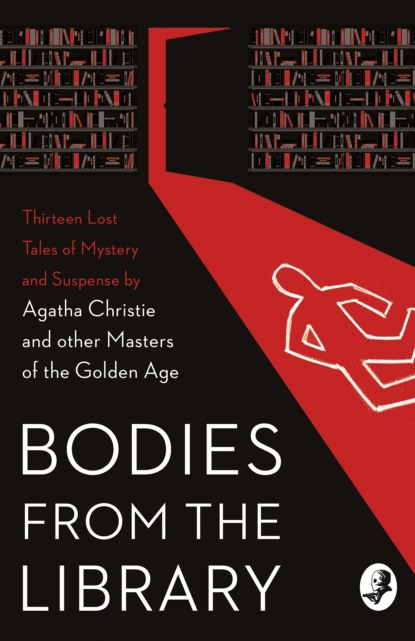

Bodies from the Library: Lost Tales of Mystery and Suspense by Agatha Christie and other Masters of the Golden Age

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At that Tony had opened her eyes wide.

‘Well, naturally. He’s like a dear elder brother, and I’ve known him ever since I was a kid.’

Linckes’ depressed spirits suddenly soared high. A little colour stole up to the roots of his brown hair.

‘You bet I’ll never rest till I’ve found the man who’s doing the dirty on us all!’ he said impulsively. ‘Would you—er—Would you be pleased if I discovered who it is, Miss Caryu?’

Tony had become suddenly interested in her shoe-buckles.

‘I—I hope you’ll do the deed, certainly,’ she answered.

Linckes took his courage in both hands.

‘I mean to. And—and if I do succeed I’m going to ask you a question, Tony.’

‘Oh—oh, are you?’ had said Tony in a small voice.

Not many days after his conversation with Tony, Linckes presented himself at Winthrop’s house, with nothing at all to report. He found Sir Charles writing at his desk. He barely looked up at Linckes’ entry, and the detective knew that one of his black moods was upon him.

‘Oh, hallo!’ said Sir Charles. ‘Sit down! Any news?’

‘Not much. The butler is now wiped off the list of possibles.’

‘Well, I never thought he was a possible.’ Winthrop pushed his chair back impetuously. ‘I’m dead sick of the whole business! The wretched culprit, whoever he is, is just one too many for us.’

‘I’m dashed if he is!’ Winthrop’s ill-humour seemed to react on Linckes. ‘Hang it all, he must give himself away some time!’

‘Why? He hasn’t done it so far.’

‘Pretty soon he’ll be trying to bring off another little coup,’ said Linckes savagely, ‘and then I’ll get him!’

‘Hope you will, that’s all I can say. Help yourself to a cigarette.’

Winthrop pushed the box across to Linckes, taking out a cigarette himself. He lit it, and began to smoke in silence.

Linckes glanced at him idly, and suddenly a furrow appeared between his brows. It struck him that Winthrop was smoking in a curious way, rather as though he were puffing at a pipe. Usually he inhaled with almost every breath, sending the smoke out through his delicately chiselled nostrils.

‘If I didn’t know you loathed pipes, I should say you were in the habit of smoking one,’ remarked Linckes.

The dark eyes looked an inquiry.

‘You’re treating that unfortunate cigarette as though it were one,’ Linckes explained.

Winthrop laughed, throwing the cigarette into the fire.

‘Am I? Well, I’m worried. I suppose it’s a nervous trick. I feel inclined to do something desperate. If only there were a clue!’

Linckes sighed.

‘It’s all so hazy,’ he complained. ‘You can’t even know for certain that the plans of the submarines were sold. You, can’t prove it.’

‘Well, if the fact that Germany is building submarines almost in accordance with those plans isn’t proof enough, I’d like to know what is!’ Winthrop retorted irritably.

‘Oh, I believe they were sold all right, but it can’t be proved. ’Twasn’t as though the plans were stolen. There wasn’t even a sign of anyone having tampered with the safe. The room—’

‘For goodness’ sake don’t let’s go all over it again!’ Winthrop begged. ‘We’ve torn it to bits. Oh, yes, I’m getting peevish, aren’t I?’ He smiled reluctantly. ‘You’d be peevish in my place.’

‘You’re certainly a bit morose,’ admitted Linckes, ‘What a mercurial sort of chap you are! A fortnight ago you were perfectly cheerful, and then you were suddenly plunged in despair!’

‘Can’t help it. Made that way.’ Winthrop picked up his pen, and started to address an envelope. ‘Oh, now the beastly pen won’t write! Damn! I hate quills!’

‘Then why use them?’

‘Heaven knows! I used to like them awfully. Yes, John?’

The butler had entered the room.

‘Mr Knowles to see you, sir.’

Winthrop’s brow cleared as if by magic.

‘Knowles? Show him in, will you? I say Linckes, do you mind if I interview this man? I won’t be many minutes.’

Linckes rose at once.

‘Rather not! I’ll clear out for a bit, shall I? Can you give me a little time when you’ve finished? There are one or two questions I want to ask you.’

‘Of course! Show Mr Linckes into the drawing-room, please, John.’

Linckes went to the door just as Winthrop’s visitor entered. As he went out Linckes cast him a passing glance, and noted that he was an elderly man with grizzled black hair and a short beard and moustache. He bowed slightly, received a pleasant smile in return, which vaguely reminded him of someone, and went out.

He had not to wait long. Presently, from the drawing-room window, he saw Knowles descend the steps of the house and hail a passing taxi. As the vehicle drew up beside the kerb, he turned and saw Linckes. He nodded slightly, smiling, and after speaking to the taxi-driver got briskly into the cab. He let down the window, and as the taxi moved forward looked up at Linckes with a strangely mocking expression in his eyes.

Then the butler came to tell Linckes that Sir Charles was at liberty.

Winthrop was standing with his back to the fire when Linckes came in, smoking, and he greeted the detective with his old, sunny smile.

‘I say, I’m awfully sorry to have turfed you out like that!’ he exclaimed. ‘My time’s not my own, you know. What do you want to ask me especially? Didn’t you say there were one or two questions?’

Something about him was puzzling Linckes. The frown had quite disappeared from Winthrop’s face; the nervous, irritable movements had left him. He was smiling in his own peculiarly charming fashion, and as he looked at Linckes he sent two long columns of smoke down through his nose.

‘Every track turns out to be the wrong one,’ Linckes answered bitterly. ‘I begin to think we shall never get to the bottom of it all.’

Winthrop went to his desk and picked up the despised quill. He held it poised, smiling at Linckes.

‘Oh, come! Don’t lose hope, Linckes! Something must leak out soon.’

Linckes stared at him.