По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

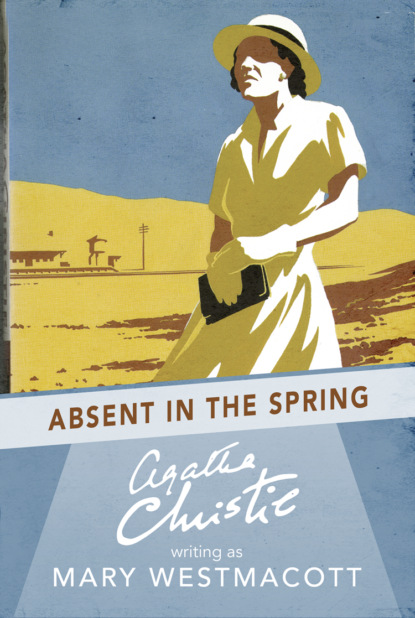

Absent in the Spring

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Joan was quick to sympathize.

‘Oh I know, darling. It’s been awfully stuffy and hard work and just sheer grind—not even interesting. But a partnership is different—I mean you’ll have an interest in the whole thing.’

‘In contracts, leases, messuages, covenants, whereas, insomuch as heretofore—’

Some absurd legal rigmarole he had trotted out, his mouth laughing, his eyes sad and pleading—pleading so hard with her. And she loved Rodney so much!

‘But it’s always been understood that you’d go into the firm.’

‘Oh I know, I know. But how was I to guess I’d hate it so?’

‘But—I mean—what else—what do you want to do?’

And he had said, very quickly and eagerly, the words pouring out in a rush:

‘I want to farm. There’s Little Mead coming into the market. It’s in a bad state—Horley’s neglected it—but that’s why one could get it cheap—and it’s good land, mark you …’

And he had hurried on, outlining plans, talking in such technical terms that she had felt quite bewildered for she herself knew nothing of wheat or barley or the rotation of crops, or of pedigreed stocks or dairy herds.

She could only say in a dismayed voice:

‘Little Mead—but that’s right out under Asheldown—miles from anywhere.’

‘It’s good land, Joan—and a good position …’

He was off again. She’d had no idea that Rodney could be so enthusiastic, could talk so much and with such eagerness.

She said doubtfully, ‘But darling, would you ever make a living out of it?’

‘A living? Oh yes—a bare living anyway.’

‘That’s what I mean. People always say there’s no money in farming.’

‘Oh, there isn’t. Not unless you’re damned lucky—or unless you’ve got a lot of capital.’

‘Well, you see—I mean, it isn’t practical.’

‘Oh, but it is, Joan. I’ve got a little money of my own, remember, and with the farm paying its way and making a bit over we’d be all right. And think of the wonderful life we’d have! It’s grand, living on a farm!’

‘I don’t believe you know anything about it.’

‘Oh yes, I do. Didn’t you know my mother’s father was a big farmer in Devonshire? We spent our holidays there as children. I’ve never enjoyed myself so much.’

It’s true what they say, she had thought, men are just like children …

She said gently, ‘I daresay—but life isn’t holidays. We’ve got the future to think of, Rodney. There’s Tony.’

For Tony had been a baby of eleven months then.

She added, ‘And there may be—others.’

He looked a quick question at her, and she smiled and nodded.

‘But don’t you see, Joan, that makes it all the better? It’s a good place for children, a farm. It’s a healthy place. They have fresh eggs and milk, and run wild and learn how to look after animals.’

‘Oh but, Rodney, there are lots of other things to consider. There’s their schooling. They must go to good schools. And that’s expensive. And boots and clothes and teeth and doctors. And making nice friends for them. You can’t just do what you want to do. You’ve got to consider children if you bring them into the world. After all, you’ve got a duty to them.’

Rodney said obstinately, but there was a question in his voice this time, ‘They’d be happy …’

‘It’s not practical, Rodney, really it isn’t. Why, if you go into the firm you may be making as much as two thousand pounds a year some day.’

‘Easily, I should think. Uncle Harry makes more than that.’

‘There! You see! You can’t turn a thing like that down. It would be madness!’

She had spoken very decidedly, very positively. She had got, she saw, to be firm about this. She must be wise for the two of them. If Rodney was blind to what was best for him, she must assume the responsibility. It was so dear and silly and ridiculous, this farming idea. He was like a little boy. She felt strong and confident and maternal.

‘Don’t think I don’t understand and sympathize, Rodney,’ she said. ‘I do. But it’s just one of those things that isn’t real.’

He had interrupted to say that farming was real enough.

‘Yes, but it’s just not in the picture. Our picture. Here you’ve got a wonderful family business with a first-class opening in it for you—and a really quite amazingly generous proposition from your uncle—’

‘Oh, I know. It’s far better than I ever expected.’

‘And you can’t—you simply can’t turn it down! You’d regret it all your life if you did. You’d feel horribly guilty.’

He muttered, ‘That bloody office!’

‘Oh, Rodney, you don’t really hate it as much as you think you do.’

‘Yes, I do. I’ve been in it five years, remember. I ought to know what I feel.’

‘You’ll get used to it. And it will be different now. Quite different. Being a partner, I mean. And you’ll end by getting quite interested in the work—and in the people you come across. You’ll see, Rodney—you’ll end by being perfectly happy.’

He had looked at her then—a long sad look. There had been love in it, and despair and something else, something that had been, perhaps, a last faint flicker of hope …

‘How do you know,’ he had asked, ‘that I shall be happy?’

And she had answered briskly and gaily, ‘I’m quite sure you will. You’ll see.’

And she had nodded brightly and with authority.

He had sighed and said abruptly: ‘All right then. Have it your own way.’

Yes, Joan thought, that was really a very narrow shave. How lucky for Rodney that she had held firm and not allowed him to throw away his career for a mere passing craze! Men, she thought, would make sad messes of their lives if it weren’t for women. Women had stability, a sense of reality …

Yes, it was lucky for Rodney he’d had her.