По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

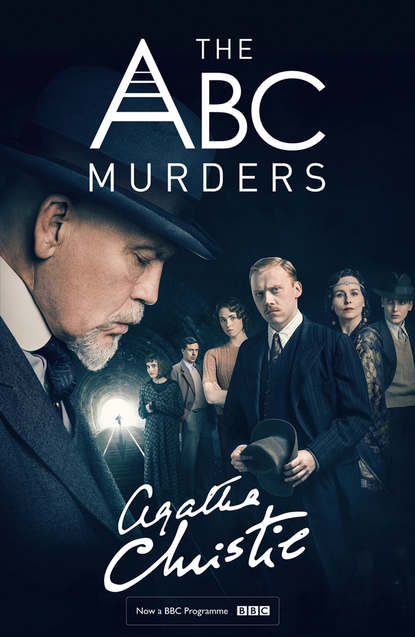

The ABC Murders

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No, because there are no curiously twisted daggers, no blackmail, no emerald that is the stolen eye of a god, no untraceable Eastern poisons. You have the melodramatic soul, Hastings. You would like, not one murder, but a series of murders.’

‘I admit,’ I said, ‘that a second murder in a book often cheers things up. If the murder happens in the first chapter, and you have to follow up everybody’s alibi until the last page but one—well, it does get a bit tedious.’

The telephone rang and Poirot rose to answer.

‘’Allo,’ he said. ‘’Allo. Yes, it is Hercule Poirot speaking.’

He listened for a minute or two and then I saw his face change.

His own side of the conversation was short and disjointed.

‘Mais oui…’

‘Yes, of course…’

‘But yes, we will come…’

‘Naturally…’

‘It may be as you say…’

‘Yes, I will bring it. A tout à l’heure then.’

He replaced the receiver and came across the room to me.

‘That was Japp speaking, Hastings.’

‘Yes?’

‘He had just got back to the Yard. There was a message from Andover…’

‘Andover?’ I cried excitedly.

Poirot said slowly:

‘An old woman of the name of Ascher who keeps a little tobacco and newspaper shop has been found murdered.’

I think I felt ever so slightly damped. My interest, quickened by the sound of Andover, suffered a faint check. I had expected something fantastic—out of the way! The murder of an old woman who kept a little tobacco shop seemed, somehow, sordid and uninteresting.

Poirot continued in the same slow, grave voice:

‘The Andover police believe they can put their hand on the man who did it—’

I felt a second throb of disappointment.

‘It seems the woman was on bad terms with her husband. He drinks and is by way of being rather a nasty customer. He’s threatened to take her life more than once.

‘Nevertheless,’ continued Poirot, ‘in view of what has happened, the police there would like to have another look at the anonymous letter I received. I have said that you and I will go down to Andover at once.’

My spirits revived a little. After all, sordid as this crime seemed to be, it was a crime, and it was a long time since I had had any association with crime and criminals.

I hardly listened to the next words Poirot said. But they were to come back to me with significance later.

‘This is the beginning,’ said Hercule Poirot.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_3ad63d93-4762-5415-b332-910f6cd2bef1)

Mrs Ascher (#ulink_3ad63d93-4762-5415-b332-910f6cd2bef1)

We were received at Andover by Inspector Glen, a tall fair-haired man with a pleasant smile.

For the sake of conciseness I think I had better give a brief résumé of the bare facts of the case.

The crime was discovered by Police Constable Dover at 1 am on the morning of the 22nd. When on his round he tried the door of the shop and found it unfastened, he entered and at first thought the place was empty. Directing his torch over the counter, however, he caught sight of the huddled-up body of the old woman. When the police surgeon arrived on the spot it was elicited that the woman had been struck down by a heavy blow on the back of the head, probably while she was reaching down a packet of cigarettes from the shelf behind the counter. Death must have occurred about nine to seven hours previously.

‘But we’ve been able to get it down a bit nearer than that,’ explained the inspector. ‘We’ve found a man who went in and bought some tobacco at 5.30. And a second man went in and found the shop empty, as he thought, at five minutes past six. That puts the time at between 5.30 and 6.5. So far I haven’t been able to find anyone who saw this man Ascher in the neighbourhood, but, of course, it’s early as yet. He was in the Three Crowns at nine o’clock pretty far gone in drink. When we get hold of him he’ll be detained on suspicion.’

‘Not a very desirable character, inspector?’ asked Poirot.

‘Unpleasant bit of goods.’

‘He didn’t live with his wife?’

‘No, they separated some years ago. Ascher’s a German. He was a waiter at one time, but he took to drink and gradually became unemployable. His wife went into service for a bit. Her last place was as cook-housekeeper to an old lady, Miss Rose. She allowed her husband so much out of her wages to keep himself, but he was always getting drunk and coming round and making scenes at the places where she was employed. That’s why she took the post with Miss Rose at The Grange. It’s three miles out of Andover, dead in the country. He couldn’t get at her there so well. When Miss Rose died, she left Mrs Ascher a small legacy, and the woman started this tobacco and newsagent business—quite a tiny place—just cheap cigarettes and a few newspapers—that sort of thing. She just about managed to keep going. Ascher used to come round and abuse her now and again and she used to give him a bit to get rid of him. She allowed him fifteen shillings a week regular.’

‘Had they any children?’ asked Poirot.

‘No. There’s a niece. She’s in service near Overton. Very superior, steady young woman.’

‘And you say this man Ascher used to threaten his wife?’

‘That’s right. He was a terror when he was in drink—cursing and swearing that he’d bash her head in. She had a hard time, did Mrs Ascher.’

‘What age of woman was she?’

‘Close on sixty—respectable and hard-working.’

Poirot said gravely:

‘It is your opinion, inspector, that this man Ascher committed the crime?’

The inspector coughed cautiously.

‘It’s a bit early to say that, Mr Poirot, but I’d like to hear Franz Ascher’s own account of how he spent yesterday evening. If he can give a satisfactory account of himself, well and good—if not—’

His pause was a pregnant one.

‘Nothing was missing from the shop?’