По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

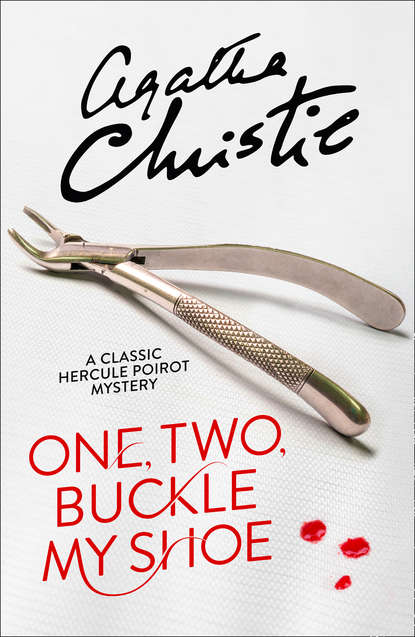

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Any special trouble?’ Mr Morley inquired.

Slightly indistinctly, owing to the difficulty of forming consonants while keeping the mouth open, Hercule Poirot was understood to say that there was no special trouble. This was, indeed, the twice yearly overhaul that his sense of order and neatness demanded. It was, of course, possible that there might be nothing to do … Mr Morley might, perhaps, overlook that second tooth from the back from which those twinges had come … He might—but it was unlikely—for Mr Morley was a very good dentist.

Mr Morley passed slowly from tooth to tooth, tapping and probing, murmuring little comments as he did so.

‘That filling is wearing down a little—nothing serious, though. Gums are in pretty good condition, I’m glad to see.’ A pause at a suspect, a twist of the probe—no, on again, false alarm. He passed to the lower side. One, two—on to three?—No—‘The dog,’ Hercule Poirot thought in confused idiom, ‘has seen the rabbit!’

‘A little trouble here. Not been giving you any pain? Hm, I’m surprised.’ The probe went on.

Finally Mr Morley drew back, satisfied.

‘Nothing very serious. Just a couple of fillings—and a trace of decay on that upper molar. We can get it all done, I think, this morning.’

He turned on a switch and there was a hum. Mr Morley unhooked the drill and fitted a needle to it with loving care.

‘Guide me,’ he said briefly, and started the dread work.

It was not necessary for Poirot to avail himself of this permission, to raise a hand, to wince, or even to yell. At exactly the right moment, Mr Morley stopped the drill, gave the brief command ‘Rinse,’ applied a little dressing, selected a new needle and continued. The ordeal of the drill was terror rather than pain.

Presently, while Mr Morley was preparing the filling, conversation was resumed.

‘Have to do this myself this morning,’ he explained. ‘Miss Nevill has been called away. You remember Miss Nevill?’

Poirot untruthfully assented.

‘Called away to the country by the illness of a relative. Sort of thing that does happen on a busy day. I’m behind-hand already this morning. The patient before you was late. Very vexing when that happens. It throws the whole morning out. Then I have to fit in an extra patient because she is in pain. I always allow a quarter of an hour in the morning in case that happens. Still, it adds to the rush.’

Mr Morley peered into his little mortar as he ground. Then he resumed his discourse.

‘I’ll tell you something that I’ve always noticed, M. Poirot. The big people—the important people—they’re always on time—never keep you waiting. Royalty, for instance. Most punctilious. And these big City men are the same. Now this morning I’ve got a most important man coming—Alistair Blunt!’

Mr Morley spoke the name in a voice of triumph.

Poirot, prohibited from speech by several rolls of cotton wool and a glass tube that gurgled under his tongue, made an indeterminate noise.

Alistair Blunt! Those were the names that thrilled nowadays. Not Dukes, not Earls, not Prime Ministers. No, plain Mr Alistair Blunt. A man whose face was almost unknown to the general public—a man who only figured in an occasional quiet paragraph. Not a spectacular person.

Just a quiet nondescript Englishman who was the head of the greatest banking firm in England. A man of vast wealth. A man who said Yes and No to Governments. A man who lived a quiet, unobtrusive life and never appeared on a public platform or made speeches. Yet a man in whose hands lay supreme power.

Mr Morley’s voice still held a reverent tone as he stood over Poirot ramming the filling home.

‘Always comes to his appointments absolutely on time. Often sends his car away and walks back to his office. Nice, quiet, unassuming fellow. Fond of golf and keen on his garden. You’d never dream he could buy up half Europe! Just like you and me.’

A momentary resentment rose in Poirot at this offhand coupling of names. Mr Morley was a good dentist, yes, but there were other good dentists in London. There was only one Hercule Poirot.

‘Rinse, please,’ said Mr Morley.

‘It’s the answer, you know, to their Hitlers and Mussolinis and all the rest of them,’ went on Mr Morley, as he proceeded to tooth number two. ‘We don’t make a fuss over here. Look how democratic our King and Queen are. Of course, a Frenchman like you, accustomed to the Republican idea—’

‘I ah nah a Frahah—I ah—ah a Benyon.’

‘Tchut—tchut—’ said Mr Morley sadly. ‘We must have the cavity completely dry.’ He puffed hot air relentlessly on it.

Then he went on:

‘I didn’t realize you were a Belgian. Very interesting. Very fine man, King Leopold, so I’ve always heard. I’m a great believer in the tradition of Royalty myself. The training is good, you know. Look at the remarkable way they remember names and faces. All the result of training—though of course some people have a natural aptitude for that sort of thing. I, myself, for instance. I don’t remember names, but it’s remarkable the way I never forget a face. One of my patients the other day, for instance—I’ve seen that patient before. The name meant nothing to me—but I said to myself at once, “Now where have I met you before?” I’ve not remembered yet—but it will come back to me—I’m sure of it. Just another rinse, please.’

The rinse accomplished, Mr Morley peered critically into his patient’s mouth.

‘Well, I think that seems all right. Just close—very gently … Quite comfortable? You don’t feel the filling at all? Open again, please. No, that seems quite all right.’

The table swung back, the chair swung round.

Hercule Poirot descended, a free man.

‘Well, goodbye, M. Poirot. Not detected any criminals in my house, I hope?’

Poirot said with a smile:

‘Before I came up, every one looked to me like a criminal! Now, perhaps, it will be different!’

‘Ah, yes, a great deal of difference between before and after! All the same, we dentists aren’t such devils now as we used to be! Shall I ring for the lift for you?’

‘No, no, I will walk down.’

‘As you like—the lift is just by the stairs.’

Poirot went out. He heard the taps start to run as he closed the door behind him.

He walked down the two flights of stairs. As he came to the last bend, he saw the Anglo-Indian Colonel being shown out. Not at all a bad-looking man, Poirot reflected mellowly. Probably a fine shot who had killed many a tiger. A useful man—a regular outpost of Empire.

He went into the waiting-room to fetch his hat and stick which he had left there. The restless young man was still there, somewhat to Poirot’s surprise. Another patient, a man, was reading the Field.

Poirot studied the young man in his newborn spirit of kindliness. He still looked very fierce—and as though he wanted to do a murder—but not really a murderer, thought Poirot kindly. Doubtless, presently, this young man would come tripping down the stairs, his ordeal over, happy and smiling and wishing no ill to anyone.

The page-boy entered and said firmly and distinctly:

‘Mr Blunt.’

The man at the table laid down the Field and got up. A man of middle height, of middle age, neither fat nor thin. Well dressed, quiet.

He went out after the boy.

One of the richest and most powerful men in England—but he still had to go to the dentist just like anybody else, and no doubt felt just the same as anybody else about it!

These reflections passing through his mind, Hercule Poirot picked up his hat and stick and went to the door. He glanced back as he did so, and the startled thought went through his mind that that young man must have very bad toothache indeed.

In the hall Poirot paused before the mirror there to adjust his moustaches, slightly disarranged as the result of Mr Morley’s ministrations.