По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

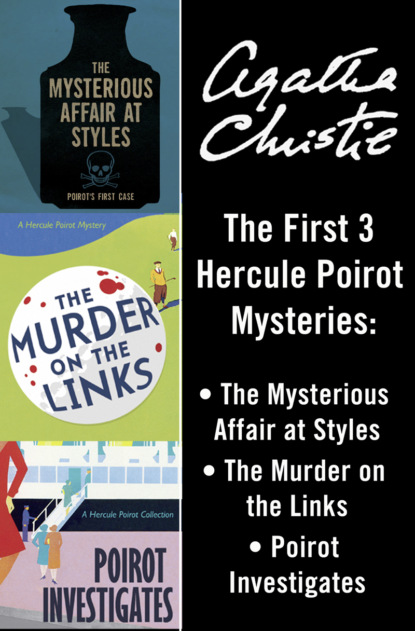

Hercule Poirot 3-Book Collection 1: The Mysterious Affair at Styles, The Murder on the Links, Poirot Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This proceeding of Poirot’s, in respect of the cocoa, puzzled me intensely. I could see neither rhyme nor reason in it. However, my confidence in him, which at one time had rather waned, was fully restored since his belief in Alfred Inglethorp’s innocence had been so triumphantly vindicated.

The funeral of Mrs Inglethorp took place the following day, and on Monday, as I came down to a late breakfast, John drew me aside, and informed me that Mr Inglethorp was leaving that morning, to take up his quarters at the Stylites Arms, until he should have completed his plans.

‘And really it’s a great relief to think he’s going, Hastings,’ continued my honest friend. ‘It was bad enough before, when we thought he’d done it, but I’m hanged if it isn’t worse now, when we all feel guilty for having been so down on the fellow. The fact is, we’ve treated him abominably. Of course, things did look black against him. I don’t see how anyone could blame us for jumping to the conclusions we did. Still, there it is, we were in the wrong, and now there’s a beastly feeling that one ought to make amends; which is difficult, when one doesn’t like the fellow a bit better than one did before. The whole thing’s damned awkward! And I’m thankful he’s had the tact to take himself off. It’s a good thing Styles wasn’t the mater’s to leave to him. Couldn’t bear to think of the fellow lording it here. He’s welcome to her money.’

‘You’ll be able to keep up the place all right?’ I asked.

‘Oh, yes. There are the death duties, of course, but half my father’s money goes with the place, and Lawrence will stay with us for the present, so there is his share as well. We shall be pinched at first, of course, because, as I once told you, I am in a bit of a hole financially myself. Still, the Johnnies will wait now.’

In the general relief at Inglethorp’s approaching departure, we had the most genial breakfast we had experienced since the tragedy. Cynthia, whose young spirits were naturally buoyant, was looking quite her pretty self again, and we all, with the exception of Lawrence, who seemed unalterably gloomy and nervous, were quietly cheerful, at the opening of a new and hopeful future.

The papers, of course, had been full of the tragedy. Glaring headlines, sandwiched biographies of every member of the household, subtle innuendoes, the usual familiar tag about the police having a clue. Nothing was spared us. It was a slack time. The war was momentarily inactive, and the newspapers seized with avidity on this crime in fashionable life: ‘The Mysterious Affair at Styles’ was the topic of the moment.

Naturally it was very annoying for the Cavendishes. The house was constantly besieged by reporters, who were consistently denied admission, but who continued to haunt the village and the grounds, where they lay in wait with cameras, for any unwary members of the household. We all lived in a blast of publicity. The Scotland Yard men came and went, examining, questioning, lynx-eyed and reserved of tongue. Towards what end they were working, we did not know. Had they any clue, or would the whole thing remain in the category of undiscovered crimes?

After breakfast, Dorcas came up to me rather mysteriously, and asked if she might have a few words with me.

‘Certainly. What is it, Dorcas?’

‘Well, it’s just this, sir. You’ll be seeing the Belgian gentleman today perhaps?’ I nodded. ‘Well, sir, you know how he asked me so particular if the mistress, or anyone else, had a green dress?’

‘Yes, yes. You have found one?’ My interest was aroused.

‘No, not that, sir. But since then I’ve remembered what the young gentlemen’—John and Lawrence were still the ‘young gentlemen’ to Dorcas—‘call the “dressing-up box”. It’s up in the front attic, sir. A great chest, full of old clothes and fancy dresses, and what not. And it came to me sudden like that there might be a green dress amongst them. So, if you’d tell the Belgian gentleman –’

‘I will tell him, Dorcas,’ I promised.

‘Thank you very much, sir. A very nice gentleman he is, sir. And quite a different class from them two detectives from London, what goes prying about, and asking questions. I don’t hold with foreigners as a rule, but from what the newspapers says I make out as how these brave Belgies isn’t the ordinary run of foreigners and certainly he’s a most polite spoken gentleman.’

Dear old Dorcas! As she stood there, with her honest face upturned to mine, I thought what a fine specimen she was of the old-fashioned servant that is so fast dying out.

I thought I might as well go down to the village at once, and look up Poirot; but I met him half-way, coming up to the house, and at once gave him Dorcas’s message.

‘Ah, the brave Dorcas! We will look at the chest, although—but no matter—we will examine it all the same.’

We entered the house by one of the windows. There was no one in the hall, and we went straight up to the attic.

Sure enough, there was the chest, a fine old piece, all studded with brass nails, and full to overflowing with every imaginable type of garment.

Poirot bundled everything out on the floor with scant ceremony. There were one or two green fabrics of varying shades; but Poirot shook his head over them all. He seemed somewhat apathetic in the search, as though he expected no great results from it. Suddenly he gave an exclamation.

‘What is it?’

‘Look!’

The chest was nearly empty, and there, reposing right at the bottom, was a magnificent black beard.

‘Ohó!’ said Poirot. ‘Ohó!’ He turned it over in his hands, examining it closely. ‘New,’ he remarked. ‘Yes, quite new.’

After a moment’s hesitation, he replaced it in the chest, heaped all the other things on top of it as before, and made his way briskly downstairs. He went straight to the pantry, where we found Dorcas busily polishing her silver.

Poirot wished her good morning with Gallic politeness, and went on:

‘We have been looking through that chest, Dorcas. I’m much obliged to you for mentioning it. There is, indeed, a fine collection there. Are they often used, may I ask?’

‘Well, sir, not very often nowadays, though from time to time we do have what the young gentlemen call “a dress-up night”. And very funny it is sometimes, sir. Mr Lawrence, he’s wonderful. Most comic! I shall never forget the night he came down as the Char of Persia, I think he called it—a sort of Eastern King it was. He had the big paper knife in his hand, and “Mind, Dorcas,” he says, “you’ll have to be very respectful. This is my specially sharpened scimitar, and it’s off with your head if I’m at all displeased with you!” Miss Cynthia, she was what they call an Apache, or some such name—a Frenchified sort of cut-throat, I take it to be. A real sight she looked. You’d never have believed a pretty young lady like that could have made herself into such a ruffian. Nobody would have known her.’

‘These evenings must have been great fun,’ said Poirot genially. ‘I suppose Mr Lawrence wore that fine black beard in the chest upstairs, when he was Shah of Persia?’

‘He did have a beard, sir,’ replied Dorcas, smiling. ‘And well I know it, for he borrowed two skeins of my black wool to make it with! And I’m sure it looked wonderfully natural at a distance. I didn’t know as there was a beard up there at all. It must have been got quite lately, I think. There was a red wig, I know, but nothing else in the way of hair. Burnt corks they use mostly—though ’tis messy getting it off again. Miss Cynthia was a Negress once, and, oh, the trouble she had.’

‘So Dorcas knows nothing about that black beard,’ said Poirot thoughtfully, as we walked out into the hall again.

‘Do you think it is the one?’ I whispered eagerly.

Poirot nodded.

‘I do. You noticed it had been trimmed?’

‘No.’

‘Yes. It was cut exactly the shape of Mr Inglethorp’s and I found one or two snipped hairs. Hastings, this affair is very deep.’

‘Who put it in the chest, I wonder?’

‘Someone with a good deal of intelligence,’ remarked Poirot drily. ‘You realize that he chose the one place in the house to hide it where its presence would not be remarked? Yes, he is intelligent. But we must be more intelligent. We must be so intelligent that he does not suspect us of being intelligent at all.’

I acquiesced.

‘There, mon ami, you will be of great assistance to me.’

I was pleased with the compliment. There had been times when I hardly thought that Poirot appreciated me at my true worth.

‘Yes,’ he continued, staring at me thoughtfully, ‘you will be invaluable.’

This was naturally gratifying, but Poirot’s next words were not so welcome.

‘I must have an ally in the house,’ he observed reflectively.

‘You have me,’ I protested.

‘True, but you are not sufficient.’

I was hurt, and showed it. Poirot hurried to explain himself.

‘You do not quite take my meaning. You are known to be working with me. I want somebody who is not associated with us in any way.’

‘Oh, I see. How about John?’